![]() Photographs can be ends in themselves as works of art; they can also participate in larger projects as documents of site-specific or ephemeral productions. Beginning in the late 1960s, in reaction to the commercialization of art in the United States, artists including Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer began to make art by creating installations in natural settings or shaping the actual landscape. The photographs, drawings, and prints they made were tangible records of the projects as well as freestanding works of art. This approach, variously called “Land Art,” “Earthworks,” and “Earth Art,” has had a lasting impact on contemporary artists, including the Hungarian-born American concept-based artist, Agnes Denes.

Photographs can be ends in themselves as works of art; they can also participate in larger projects as documents of site-specific or ephemeral productions. Beginning in the late 1960s, in reaction to the commercialization of art in the United States, artists including Robert Smithson and Michael Heizer began to make art by creating installations in natural settings or shaping the actual landscape. The photographs, drawings, and prints they made were tangible records of the projects as well as freestanding works of art. This approach, variously called “Land Art,” “Earthworks,” and “Earth Art,” has had a lasting impact on contemporary artists, including the Hungarian-born American concept-based artist, Agnes Denes.

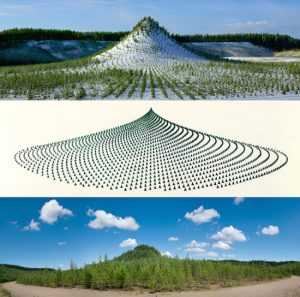

Denes’ work has centered on environmental and ecological issues, with site-specific installations that examine land-reclamation, re-forestation, and human interaction with nature. The artist describes Tree-Mountain – A Living Time Capsule, conceived in 1982, as “a collaborative, environmental project that touches on global, ecological, social, and cultural issues.”[footnote]Agnes Denes, “Tree Mountain – A Living Time Capsule, 11,000 Trees, 11,000 People, 400 Years (1982-96),” unpublished document provided by the artist to the Middlebury College Museum of Art.[/footnote]

Between 1992 and 1996, 11,000 people planted 11,000 pine trees the Pinziö gravel pits, in Ylöjärvi, Finland to restore land that had been deforested through resource extraction. This natural “time capsule” exists on land set aside for 400 years. According to the artist, although the trees remain the property of the people who planted them, the trees may not be moved form the forest, and Tree Mountain can never be owned or sold.

Placed in an intricate pattern based on mathematical formula, the pattern visualized human intellect in harmony with nature, and the artist envisions this act of bioremediation lasting for centuries. Denes notes, “The trees must out-live the present era and, by surviving, carry our concepts into an unknown time in the future. If civilization as we know it ends or changes, there will be a reminder in the form of a strange forest for our descendants to ponder. They may reflect on an undertaking that did not serve personal needs but the common good and the highest ideals of humanity and its environment, while benefiting future generations.”[footnote]Agnes Denes, “Tree Mountain – A Living Time Capsule, 11,000 Trees, 11,000 People, 400 Years (1982-96),” unpublished document provided by the artist to the Middlebury College Museum of Art.[/footnote]