Parable of the Sower: A Positive Afrofuturist Obsession

1May 28, 2021 by John Hall

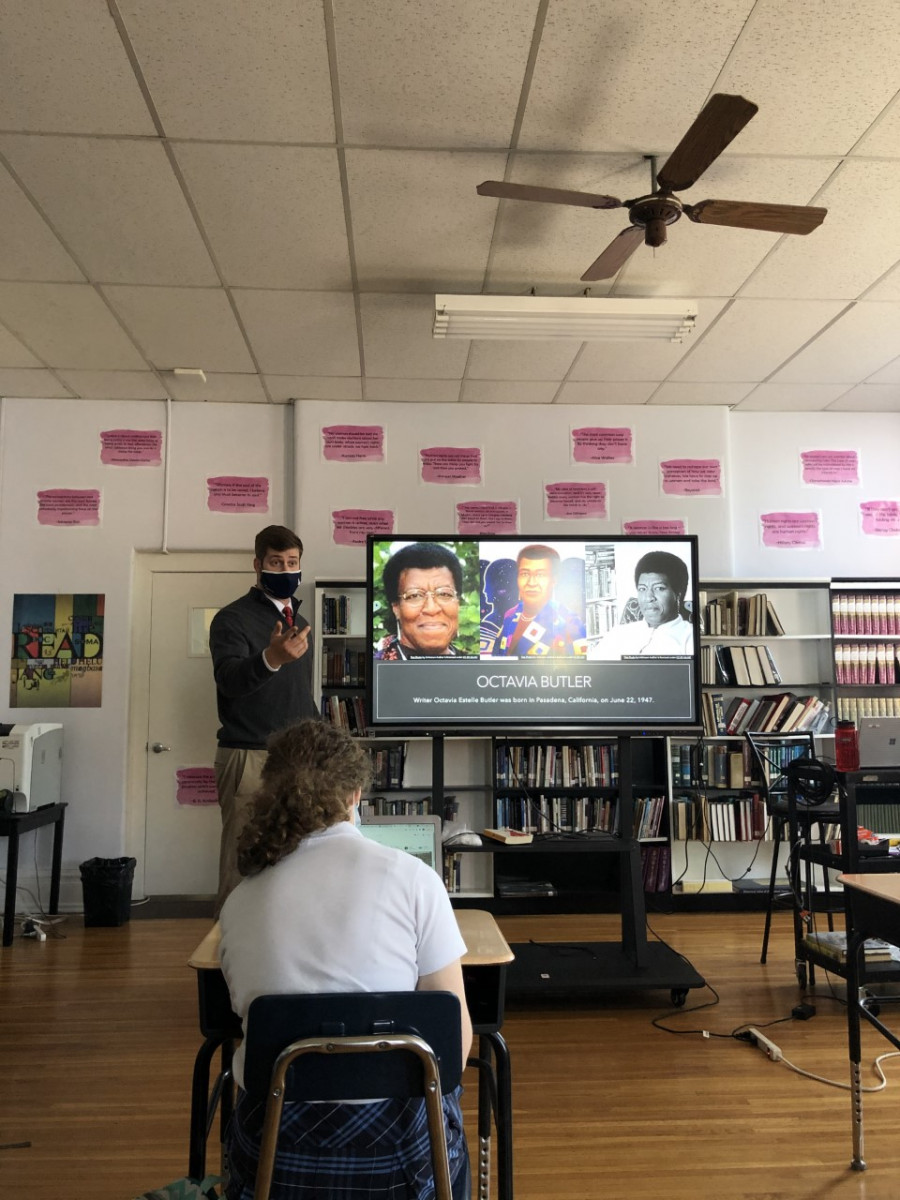

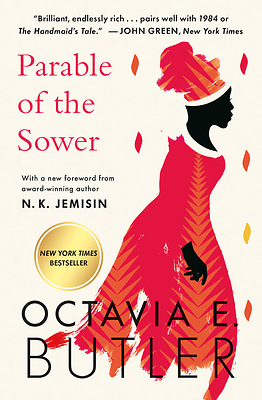

When I first read Parable of the Sower in a 2017 Bread Loaf School of English class titled Cli-fi, it gave me chills. The apocalyptic novel, published in 1993 and set in 2024, seems prophetic, and in no uncertain terms, eerie. Butler’s work stood out to me because it was so prescient and seemed to predict, if not describe, the United States we live in or will soon live in. Now, in my third read and using it as a main text in my junior English class, I’m finding the novel to be absolutely relevant, pedagogically and politically. My students and I have used the text as a lens through which to think about cycles of history, to analyze our present world, and to dream up new futures.

I’ve become aware of how the past informs the present and the future informs the past, a key signature of Parable’s genre, Afrofuturism. Coming off the anniversary of the Covid-19 lockdown and Breonna Taylor’s death in Louisville, and with the George Floyd trial resolved, I’m called to remember why I chose Parable of the Sower as a core text for my American Literature curriculum this year. Last June, when I began the summer writing tutorial with Dr. Andrea Lunsford, I was attempting to make sense of the world. Protests against police brutality and white supremacy arrived at a boiling point in the United States. Federal officers and protesters clashed in Portland, Oregon, militias held counter protests in Louisville, all while a global pandemic ramped up across the country and world.

I could turn on any news channel, scroll through Twitter, or click on any news feed, and find what was seemingly the plot of a science fiction novel. George Orwell, Phillip K. Dick, Ursula K. Le Guin, or Octavia Butler would have had a hard time coming up with a more dystopian plot than what we witnessed and continued to witness: the escalation of a pandemic, the government denying science, state senators arguing slavery was a necessary evil, a far-right politcal movement gaining traction, and massive protests weaving in and out of the streets of America.

During the Summer of 2020, conversations with BLTN colleagues raised challenges and opportunities for creating anti-racist teaching and learning spaces. In what I’d call a perfect Bread Loaf pedagogical storm, I discovered that Afrofuturism must hold a place in the contemporary English classroom, because of its decolonizing, anti-racist themes and imaginative potential. So I turned to Parable and studied Afrofuturism, as I listened and learned in BLTN conversations.

Afrofuturism, a sub-genre of speculative fiction, offers a critical lens to center the Black experience, and to lead teachers and students to analyze, synthesize, and discuss current social, environmental, and political issues. The pedagogical allure of speculative fiction is that it centers discussions of social justice around hope, and around what we want or don’t want our world, society, and country to look like. In the imagining of futures with Black perspectives featured prominently, students and teachers alike can resist and critique the present and the past. To give our students the lens of Afrofuturism is to give them a uniquely imaginative and restorative power.

The term Afrofuturism was coined by Mark Dery, author and cultural critic, in his 1994 essay “Black to the Future.” He defines Afrofuturism as “speculative fiction that treats African-American concerns in the context of twentieth-century technoculture–and more generally, African-American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically enhanced future” (Dery 180). Moreover, Afrofuturism draws on science fiction imagery and futuristic ideals to reflect upon the marginalization and hope of Black people. It is a sub-genre of speculative fiction that is multi-modal: including music, dance, art, protest, and literature. Cauleen Smith, experimental filmmaker and multimedia artist, describes Afrofuturism as “the experience of cognitive estrangement as manifested through sound, image, language, that so often defines or frames the mundane conditions and movements and generative thought in the African Diaspora” (Womack 138).

To make the case for teaching Afrofuturism, I would first like to highlight how it differs from science fiction, the most well-known genre of speculative fiction. I will then highlight its major thematic concerns, and detail how they are represented in Parable of the Sower. Finally, I will outline some possible projects for the classroom. The multimodality of the genre, its centering of African American concerns and characters, and its related thematic explorations make the genre a fertile ground for the development and cultivation of anti-racist teaching.

Speculative Fiction: The Relationship Between Sci-Fi and AfroFuturism

Science fiction explores past, present, and future through time travel, alien civilizations, totalitarian governments using biological warfare against its own citizens, and much more. (Think Star Trek, Star Wars, Blade Runner, and Back to the Future.) “In traditional science fiction there are three lines of thought that drive writers: What if—[What if we built a colony on Mars?], If only—[If only we could fix past mistakes by traveling through time.], and If this goes on—[If this goes on, our world will be a dystopia.]” (Due 264). Thus, inherent in science fiction is a critique of the present and the past, which makes it an incredibly useful lens through which to compare and contrast imagined futures and the very real present. However, traditional and canonical science fiction tends to leave out Black people, Indigenous people, and people of color.

While speculative fiction provides audiences with cautionary tales and dystopian what ifs, it consistently takes a back seat to other genres, and the genre often relegates Black people to secondary characters who die off quickly—often without any nuanced discussion on how race might exist in the future. It is an ironic approach within a realm that is quick to depict superheroes, aliens, and even post-racial white people in some of the same predicaments that Black people have actually lived for the past 500 years. Forced labor, false imprisonment, involuntary biological testing, and compulsory sterilization sound like dystopian fiction but have been very real and traumatic experiences among folks within the African diaspora.

Thematic Concerns of Afrofuturism in Context of Anti-Racist Pedagogy

In 2019 NCTE created a blog post titled, “Being an Anti-Racist Educator is a Verb.” Keisha Rembert, Patrick Harris, and Felicia Hamilton, members of the NCTE Committee Against Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English, wrote the following:

Being an anti-racist educator is a verb. As our nation seems to grapple with acts of hatred more frequently, we, as educators, must consider our actions. We need to consider where we’ve spoken and where we’ve been silent in terms of quelling the growing violence our country faces. These perpetrators were once students. Our teaching must therefore be an act that addresses, challenges and dismantles racism in all its forms. Anti-racist educators actively confront and challenge racism. (NCTE)

Rembert, Harris, and Hamilton identify three principles that the anti-racist educator must enact in the classroom: Bring the realities of the present day into the classroom, use all texts strategically to give students opportunities to talk about systemic inequities, and create projects that encourage student activism.

In reading and experiencing Parable of the Sower together this year, my students and I have encountered five major critical and literary themes found in Afrofuturism that can help bring out the verb in being an anti-racist educator: alienation and otherness, reclamation of history and identity, imagining futures as a form of resistance, history as cyclical (the boomerang), and technology as a double edged sword.

Alienation and Otherness

Afrofuturists have long used the alien metaphor to explain “the looming space of otherness perpetuated by the idea of race” (Womack 34). While traditional science fiction uses the alien motif to explore how other worlds may interact with our own for better or worse, Afrofuturism uses the alien motif to explore otherness in the Black experience in America. What does it mean to be other or alien in America? What does it mean to be other in your school or neighborhood? Have you ever been made to feel you were “other”? How? How do you adapt to those stereotypes? What forms of resilience are present in your community?

Parable of the Sower is a coming of age story in which the protagonist, Lauren Olamina, must come of age immediately. Her walled community is a diverse enclave in an otherwise dog eat dog world. Lauren and her neighbors are indeed other within their apocalyptic world. Even though they differ in race, religious beliefs, and wealth, they work together to protect one another and survive and they are consistently defining and redefining who they are in opposition to the deteriorating society on the outside.

At the onset of the book, Lauren’s walled community must work together across racial, religious, and political differences to survive and protect the few resources they have. Throughout Parable of the Sower, the issue of race in community building is front and center. Butler consistently argues through plot development and conflict that Lauren’s community must “embrace diversity” or be destroyed. Lauren’s community inevitably falls due to the waves of societal disintegration outside the walls of her community, and Lauren and a few others embark on a journey north. Along the road Lauren builds a following for her new religion, Earthseed. The basis of Earthseed is embracing change and diversity. Lauren is an outsider, with a particularly mature perspective of the world. Through Lauren we see Butler’s critique of societal structures and vision for a new worldview and morality. Lauren’s unique perspective of her society makes her alien to those around her. Through our class discussions we talked about what it would mean to have a radically different perspective of the world than those around us, which led to the Make Me an Alien project.

Students created an alien personality and imagined they were looking in on earth to critique the way we do things. Alice’s project titled An Extraterrestrial Perspective on: Oh, The Humanity, A Divine Comedy, explores earth from billions of years in the future. Here’s a snippet of her work:

Overall, I find this “society”, as they call it, to be hard to believe. It is true that there is not much we know for sure about the lifestyle of this ancient species that dominated a lonely planet in the… what did they call it? Milky Way Galaxy. But are we honestly supposed to believe that they have not found a way to connect with one another in a way that solve their problems? That they worship valueless objects [such as the almighty Television]? That they argue constantly about unimportant things? I’d much rather converse with the fungi.

However, I think there is something to be learned from human beings as we see them through this lens. Though they have no physical ways of empathizing with one another, some do attempt to do so, and they are able to come together despite difference. However silly they may seem, they do fascinate me.

Alice’s foray into an alien’s perspective gave her a newfound appreciation for our capacity for empathy and the building of coalitions across difference.

Reclamation of History and Identity

The second theme we took up through Parable involves exploring and reclaiming one’s history in a white dominated discourse. Afrofuturism works to reclaim a history that was decimated by chattel slavery and colonization in both America and Africa. Former President Trump’s rejection of the 1619 project on July 19th is a perfect example of how White supremacy “others” Black history and reinforces a dominant narrative that excludes and alienates. Samuel Delaney writes, “When, indeed, we say that this country was founded on slavery, we must remember that we mean…that it was founded on the systemic, conscientious, and massive destruction of African cultural remnants” (Dery 191). The dominance of white, male, western history alienates our students and leaves them with an incomplete narrative of history. In order to reclaim lost history, Afrofuturism explores the ancient cultures, wisdom, science, and mythological ideologies of Africa from Egypt to Nubia. The destruction of African and African American knowledge through European colonizers in Africa and White supremacy in America compels Afrofuturists to “anchor their work in golden eras from time long gone” (Womack 81).

While Parable doesn’t directly address the cultural artifacts and knowledge of the African diaspora, it does clearly acknowledge indigenous knowledge and non-academic knowledge in Lauren’s preparation for social disintegration and for her survival. Before the walls of her community come crashing down, Lauren slowly gathers knowledge on how to survive. Lauren says, “I loaned Joanne a book about California plants and the ways Indians used them,” and her father responds, “You wouldn’t have the acorn bread you like so much without that [book]…most people in this country don’t eat acorns, you know. They have no tradition of eating them,” (Butler 63).

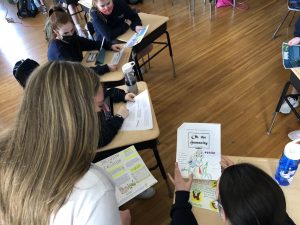

While we read this section of the book, I asked students what they would include in their prepper packs. Many said cell phones or hot spots or portable chargers, but when I pressed them to bear down on what would really matter, many turned to protection and food, so toward the end of the book, I began thinking about what non-academic knowledge structures students learn from outside of school that would truly help them in the future. In students’ “non-academic prepper packs,” an imaginative exercise we completed together, they included construction skills, knowledge of plants, their grandfather’s fishing skills, and many more. (See “Prepper Packs” in the final section of this piece.) Inspired by reclaiming what constitutes knowledge, my students acknowledged and celebrated skills and knowledge they gained outside of school.

Imagining Futures as a Form of Resistance

By acknowledging that white supremacy operates in education as a form of oppression that devalues non-white ways of thinking, assessment, or knowledge creation, teachers can open up the curriculum to the broad knowledge base that their students bring to the classroom.

Works of Afrofuturism provide scaffolds for imagining and creating a revolutionary classroom that values community knowledge and personal stories as qualitative and legitimate knowledge. This theme allows the anti-racist educator to encourage home languages, non-traditional methods of learning, and the exploration of white supremacy in knowledge generation.

Inherent in Afrofuturism’s name is a concern for the future. Afrofuturist stories, dances, pieces of art, and music consistently write the future as a form of resistance to the present, either in critique or exaltation of current social ideologies. The deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Aubrey and the rise of the Black Lives Matter protests across the world have catapulted the nation into critical introspection and necessary imagining of what we want our future to look like.

Images of protests show us memes, artwork, dancing, and spectacle that call attention to the paradox of being Black while living in the “land of the free.” Imarisha writes, “Art and culture themselves are time-traveling, planes of existence where the past, present, and future shift seamlessly in and out. And for those of us from communities with historic collective trauma, we must understand that each of us is already science fiction walking around on two legs” (11). Afrofuturism allows us to project ourselves into the future while decolonizing our imaginations from the present-possible. .

We want our students to think of their future. We want to ask them: How do you want to contribute to or change the world? What do you want the future to look like? We are asking our students to imagine a future during a global pandemic and historic social unrest.

After reviewing all of my students’ projects, I found the imagined futures project to be the most fertile for compassionate thinking. Students were to write a short reflective piece imagining how they want the world to look in the near or not so near future. Resoundingly students wrote of worlds without discrimination, poverty, hate, terminal illness, and of course, COVID.

The Boomerang of History

The cyclical nature of time is a generative Afrofuturist theme informing how we might imagine futures. Octavia Butler’s works thoroughly explore time through time travel and future planning. Marlene D. Allen notes, “Butler conceptualizes time as a cycle, or, to use the words of Ralph Ellison, as a ‘boomerang’ to denote the violent nature of the spiraling of history, especially for African Americans and other minority groups. This conception of time and history reflects the Afrocentric notion that the pains of racism and sexism of the past are ever-present and continue to affect the psyche of African Americans today” (3). The boomerang metaphor is useful to explore structural oppression in the United States, because old forms of oppression “boomerang” from the past to the present and into the future.

Slavery and Jim Crow boomerang into covert and overt forms through police brutality, the school to prison pipeline, concentrated poverty, and voter suppression. Indeed, white supremacy challenges this boomerang metaphor because it primarily looks to the past as a source of ideals for the present and future. There is a stark contrast between white supremacy’s view of time and the Afrofuturist’s. The Afrofuturists’ boomerang stands in direct opposition to white supremacy.

The boomeranging of history is not inevitable, however. Someone–many someones–have to throw the boomerang or catch the boomerang in order for it to maintain place in the present. If we can, as a society, as teachers, and as students, throw the boomerang into the future by critiquing the present and unleashing our imagination to inspire the world we want to live in, then we can change.

Ask students to imagine futures beyond the boomeranging of the past. Empower yourself to imagine a future for you and your students that challenges the structural oppression of the present. In the classroom, we must ask our students to imagine future worlds as a form of resistance. Again Afrofuturism finds itself a worthy partner of anti-racist education.

In my students’ Museum of Future’s Past project, inspired by Kurt Ostrow, (See the “Concepts for Units or Projects,” and my student Jolie’s example) students highlighted artifacts from our present. Artifacts included belief systems, ideas, physical objects, or events that would seem strange or morally wrong to those in the future. Similarly to the Imagined Futures project, students explained away systemic racism and COVID as relics of a troubled past. Students wrote of gas-powered cars as anachronisms and governments denying science as extinct.

Technology as a Double-edged Sword

Technology–the smart phone, virtual reality, artificial intelligence, self-driving cars– has caught up to a lot of science fiction inventions. Womack writes, “Afrofuturism is concerned with both the impact of these technologies on social conditions and with the power of such technologies to end the “isms” for good and safeguard humanity” (36). However, Womack notes that technology has often come at a price for marginalized people—from the Tuskegee experiments, where innocent Black men were injected with syphilis to Henriette Lacks whose cells were taken without her permission to be sold for research around the world. “Afrofuturists are highly sensitive to how or if such technologies will deepen or transcend the imbalances of race” (37). Indeed, Afrofuturists’ critical technology lens can be applied to the quick transition to online instruction most schools instituted during Covid-19. While technology has allowed us to be connected and continue school in some way, it has also highlighted the lack of access to computers and internet that many of our students experience.

Afrofuturism acknowledges that technological achievement alone is not sufficient to establish a free future; a healthy relationship with mother-nature is necessary for a balanced future. With issues of climate change pressing, Afrofuturism asks us to place technological advancements in the context of nature. This offers students and teachers the opportunity to discuss what types of technologies can create an equitable future for humankind and the natural world.

While we did not explore the theme of technology’s hidden risks in Parable itself, our work together in the other themes gave us daily opportunities to critique tech. Is that cell phone really worthy of its place in the prepper pack? What do we know about the power of social media to contribute to teen depression and alienation? To what extent do our technologies amplify systemic inequities?

Afrofuturism gives educators plots and themes that can bring students into conversation with systemic inequities and current events. It asks students to look forward to the future and ask themselves how they will engage with the present in order to shape the future. It is entirely a social justice and anti-racist endeavor.

I have illustrated five themes common in Afrofuturism through moments in our current discussions of Parable of the Sower. For a more complete discussion of textual and multimodal works that might be used in units on Afrofuturism, see my section titled Afrofuturist Works: Past, Present, and Future. Next up: Curriculum suggestions for possible units.

Five Ideas: Concepts for Units or Projects with Afrofuturist Texts

I’m including five project ideas that could be used in a unit on Afrofuturism. Consider these as whole class, small group, or independent explorations.

- Kehinde Wiley Portraits/Photos

Kehinde Wiley was made famous by his portrait of President Barack Obama in 2018. Kehinde Wiley uses poses from renaissance painters to recast young black men in street clothes. He hopes to quote historical sources and put young black men in positions of power. Students can create their own Kehinde Wiley-esque painting by dressing up how they would and by taking pictures or drawing themselves in high renaissance poses.

- Imagined New World

One of the more simple projects students can take on, is simply imagining a future world and creating a narrative surrounding their vision. These narratives can be shared in class in a read-around or in a gallery walk style format.

- Prepper Packs

We all have that crazy relative or friend who is preparing for the apocalypse. They’ve got their Campbell’s Chunky Soup and bottled water in their underground bunker. Ask your students to choose five non-academic sources of knowledge that could prepare them for whatever future they think is coming. This project relates to the Afrofuturistic theme of reclaiming non-western, non-academic, or non-white knowledge. How can we elevate different forms of knowledge within the classroom?

- Museum of Future’s Past

Have students imagine themselves as curators of a future museum. What artifacts would people in the future find surprising about our present? This project provides students with the opportunity to place what they see wrong about the world today in the eyes of a future progressive audience. A student might place a rendition of a current classroom in the museum and criticize its rows and lack of color.

- Make me an Alien

Similar to the Museum of Future’s Past project, students can imagine themselves as an alien watching a sitcom called Earth or Humanity: A Divine Comedy, etc. Students can satirize current issues and provide a critical lens through an alien’s perspective. This calls upon students to ask the questions: what is sci-fi about our life now? What would aliens find surreal about our world?

Are We Brave Enough? Imagination as Resistance

Walidah Imarisha asks, “Are we brave enough to imagine beyond the boundaries of ‘the real’ and then do the hard work of sculpting reality from our dreams?” (5). At times this year, the boundaries of “the real” have seemed impenetrable. The work we must do as anti-racist educators is daunting, especially in the face of a pandemic. However, we are experts in adaptability and ingenuity. We must challenge ourselves, now more than ever, to imagine the great possibilities of the future for our students and ourselves. We know that we must commit to the principles of anti-racist teaching: bring the realities of the present day into the classroom, use all texts strategically to give students opportunities to talk about systemic inequities, and create projects that encourage student activism.

I urge you to join me in including Afrofuturism in your English curriculum–as the basis of a unit or lesson to inspire students to critique the past and present and to imagine exciting and equitable futures. Afrofuturism asks us to dream beyond the past. It asks us to critically analyze systemic injustice. It asks us to reimagine the present so that we can have the equitable future we all so desperately desire. Providing our students with support and informed inspiration to imagine equitable, fantastic, and outlandish futures is mission critcal for anti-racist teachers. Maybe we can all learn from Lauren’s opening thoughts on adaptability and persistence, and make Afrofuturism a positive obsession.

“Prodigy is, at its essence, adaptability and persistent, positive obsession. Without persistence, what remains is an enthusiasm of the moment. Without adaptability, what remains may be channeled into destructive fanaticism. Without positive obsession, there is nothing at all” (Butler 1).

Works Cited

Allen, Marlene D. “Octavia Butler’s ‘Parable’ Novels and the ‘Boomerang’ of African American History.” Callaloo, vol. 32, no. 4, 2009, pp. 1353–1365. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/27743153. Accessed 3 Aug. 2020.

Butler, Octavia. Parable of the Sower. Grand Central Publishing, 2019.

Dery, Mark. “Black to the Future: Interviews with Samuel R Delaney, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose.” Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture, edited by Mark Dery, Duke University Press, 1994, 179-222.

Due, Tananarive. “The Only Lasting Truth: The Theme of Change in the Works of Octavia E. Butler.” Octavia’s Brood, edited by adirenne maree brown and Walidah Imarisha, AK Press, 2015, 259-277.

Hall, John. “Afrofuturism in the ELA Classroom.” https://docs.google.com/document/d/1tHYNW9aa6IbZCQJwL9qdsgysWD_SvJUvnuNe51xJJRE/edit?usp=sharing, 2020.

Inverse Original. “Afrofuturism Is More Than Just ‘Black Sci Fi,” It’s a Nuanced Black Future.” Inverse, Inverse, 10 Mar. 2018, www.inverse.com/article/42024-afrofuturism-is-not-just-black-sci-fi.

Janelle Monae. Metropolis: the Chase Suite, Bad Boy Records, 2007.

NCTE 11.06.19 Social. “Being an Anti-Racist Educator Is a Verb .” NCTE, 13 Jan. 2020, ncte.org/blog/2019/11/being-an-anti-racist-educator-is-a-verb/.

Wiley, Kehinde. Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps. 2005, Brooklyn Museum.

Womack, Ytasha. Afrofuturism: the World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture. Lawrence Hill Books, 2013.

Category Featured | Tags:

John,

This is GOLD! Thanks so much for your review of your work with Afrofuturism this year. You’ve given me a lot to consider as I bolster my own Afrofuturism mini-unit for next year. I’ve not read “Parable of the Sower,” but that will be on my summer list now. I have used Nnedi Okorafor’s short stories (“The Key” and “Hello, Moto”), but am still looking for range based on students’ interests. I am looking forward to starting my summer tutorial based on N. K. Jemison’s How Long ’til Black Future Month? Thanks for listing your sources as I look to find companion texts!

Also–I love the five project ideas. I can attest that the Kehinde Wiley portrait project is a winner! Students love picking their pose, background, and style. Looking forward to trying out the other projects.

Many thanks for your piece,

Leslie Schallock