Children of Letters: The Case for Sustained Written Dialogue as Connected Learning

0December 16, 2014 by Tom McKenna

by Tom McKenna (MA 96) and Brendan McGrath (MA 08)

Tom is Director of Communications for BLTN and a fourth grade teacher at Harborview Elementary, Juneau, Alaska. Brendan is a third grade teacher at Thomas Kenny Elementary, Dorchester, Massachusetts.

Through the course of the last three years, we have connected our distant elementary classrooms through various digital media. Our students have shared drawings and poems via Voicethread. They have shared images and presentations. They have used FaceTime, Google Hangouts, Adobe Connect, Edmodo, and Skype. But while preparing for a presentation we gave at NCTE with author Ralph Fletcher, we studied the transcripts of our connected-classroom discussion of Fletcher’s novel, Fig Pudding. What we found to be most transformative for our elementary student writers was the oldest technology in the mix: letter writing.

In our November, 2014 NCTE presentation, “A Taste of Place: Cross-Continental Fig Pudding,” we shared the story of interaction among our eight-to-ten-year-old students as they worked together to both understand Ralph Fletcher’s novel, and to use the novel and their correspondence to help find perspective on losses they have experienced or known about in their own lives. A semi-autobiographical novel, as Ralph Fletcher would reveal to our students by the project’s culmination, Fig Pudding tells the story of a New England family that works its way through tragedy via laughter and tears, much of which are generated during shared meals.

The exchange involved a third grade class (Brendan’s) at the John F. Kennedy School in the Jamaica Plain section of Boston and a fourth grade class (Tom’s) at Harborview Elementary, the downtown elementary school in Alaska’s capital city of Juneau. The exchange took place within a year-long focus on “food literacy,” a theme inspired by the work of fellow BLTNers Brent Peters, Paul Barnwell, Joe Franzen, and Rex Lee Jim. Drawing from the norms of practice of years of BLTN collaborations, we built a foundation of trust among our students with a series of personal and increasingly academic exchanges, using poetry, responses to literature, and personal talk to position our students as more than just pen pals. We realized upon review of the work, that while the students truly valued the friendship that had developed via the exchange, they had also helped one another to realize the novel’s themes through shared experiences in their lives. Conversely, each of us can point to specific children who gained voice and refined their articulation of grief through their shared encounters with the events in Fig Pudding.

Friendly Letters and Online Etiquette

“I think it’s the letters,” Dixie Goswami commented one summer morning over an early coffee. We had talked about why BreadNet has promoted sustained written dialogue and intellectual relationship-building, in contrast to the passing comments, often shallow thread-depth, and fragmented “one-off” replies we so often see on Facebook, blogs, and other social media.

As we pored over the conversations about Fig Pudding and its themes, we were struck by this little gem of insight. With both teachers asking students to use conventions of friendly letters, we found the conversations to be marked by civility and politeness, opening spaces for trust that, at times, surprised all of us. Here, for example, is a letter from Sophia to her partner, Elioner, who had written to her most recently in his native Spanish.

Dear Elioner,

I like that little story and thank you for translating. I would translate it for you but I have no single clue on how to speak Spanish except I can count to 15 and say some colors like blue and red and some other colors too. I can also say water and hello but that’s not the point. The thing I am supposed to be talking about is Fig Pudding. I would like to hear more about your story, like how old were you when that happened? Was it this year or last year or some other year?

Now I am going to talk about a time something like that. Once my dad went scuba diving. He went early in the morning and later that day, I figured out that he had run out of air in his air tank. And so he died. How my family members and I dealt with it was some other family members came down from Anchorage, Reno, and Texas but the family members from Anchorge brought my cousin Ella so how I got distracted from my dad dying. Ella and I would play with each other and my Aunt Beth who is Ella’s mom arranged a party. We got ribbons and when everybody got there they said “I am sorry for your loss,” and the house was filled with people and it was really loud so Ella and I stayed in our grandparents’ room and when everybody left they took a ribbon from the basket and tied it on our lilac tree and made a prayer, and to this day we still have every single ribbon on that tree. And that’s my story that kind of relates to Josh going to the hospital. I know it’s nothing like the story, but it’s close enough.

Your friend,

Sophia (:

Although we had discussed Sophia’s potential sensitivity to the death of a character in the novel and whether or not we should broach the subject with Sophia ahead of time, her direct revelation to her “friend,” Elioner, was on her own terms, personal, and yet still within the bounds of her academic work. Elioner soon moved back to Puerto Rico, but as Sophia progressed through the yearlong collaboration, she would engage with other writers (including Mr. McGrath) in a way that was ultimately affirming and confidence-building for her. In a recent interview about the project, she made the following comment.

“Writing the piece about my dad dying and telling this story about people coming to my grandparents’ house was hard to share, but I was positive no one would be rude or make fun of me, so I wrote about it.”

We believe the culture of civility developed through sustained letter writing goes a long way in allowing our students to “be positive” that their words and experiences will be received by interested, active, and respectful readers.

Active Listening and Empathy

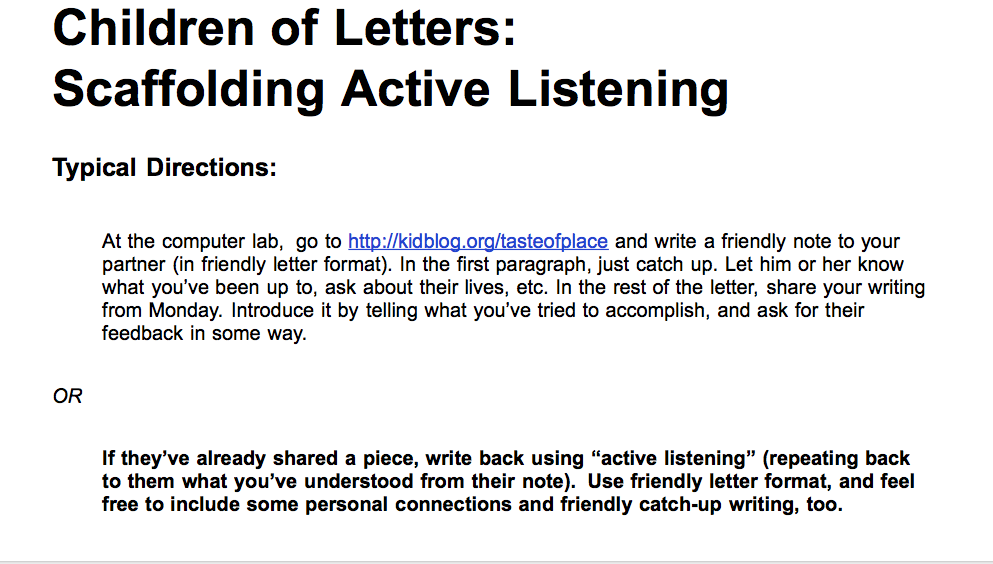

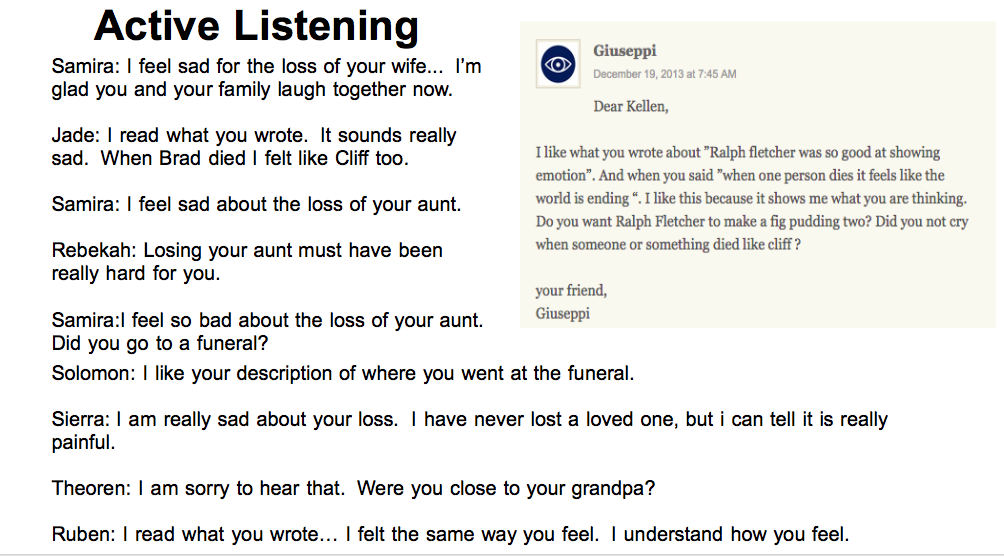

In addition to moderating the exchange, both teachers scaffolded instruction for something we have come to call “active listening.” We directly teach students how to affirm that they have read one another’s ideas. Here again, we attribute the relationships to their sustained letter writing with all the conventions of civility. Below is a set of examples we shared in our November presentation.

This slide represents one of many ways we prompted our young students to adopt the conventions of respectful written discourse with one another.

This slide provides a brief collage of the kinds of thinking and sentence construction we see throughout the exchange transcript.

Evidence and Close Reading: Common Core as Common Courtesy

In large part due to our learning from Bread Loaf’s fine faculty and students, we share a belief that our work should give students regular practice finding evidence for arguments and opinions and giving close readings of texts. Here’s just one example, from hundreds, of students making reference to specifics of text—from the novel and from one another.

Dear Aiden and Kellen,

I like the question. I noticed grandma dealt with the stress by knitting by herself. That shows me that she is dealing with the stress quietly. Another way she’s just with the stress is she cooks. She had the others cook with her. Grandma said “get nuts used in two sticks of butter”. Boy she could be a drill sergeant. She wanted to forget the sadness. I like that chapter I cannot wait to see what a yidda yadda was.

Your friend,

Giuseppi

Dear Giuseppi,

I like that question too.I can relate to what you said about how grandma knits when she is stressed out.When I get stressed out,I like to read a book.What do you do when your stressed out? I’d really like to know.

Your friend,

Kellen

In her reflections on the year-long experience, Marina, now a fifth grader at Harborview Elementary, shares her processing of Ralph Fletcher’s writing style, as she reads aloud a piece much influenced by her close attention to Fletcher’s style, from sentence structure to alternation of light and dark tones, in the poignant Fig Pudding chapter “A Steaming Bowl of Sadness.”

Your Words are Your Face

A trait we initially tapped, without true intention, was one that is most deeply inherent in any eight or nine year old: curiosity. The idea of an exchange with a student of the same age but in a completely different environment from their own created a tremendous amount of questions. The simple question “Are you a boy or a girl?” was sometimes challenging to decipher through name introductions for some. It became immediately evident that the students’ written words would have to replace their most primal sense of identification: their faces. With this challenge, students were impelled to make more careful writing choices and pay more keen attention to conventions than we had anticipated.

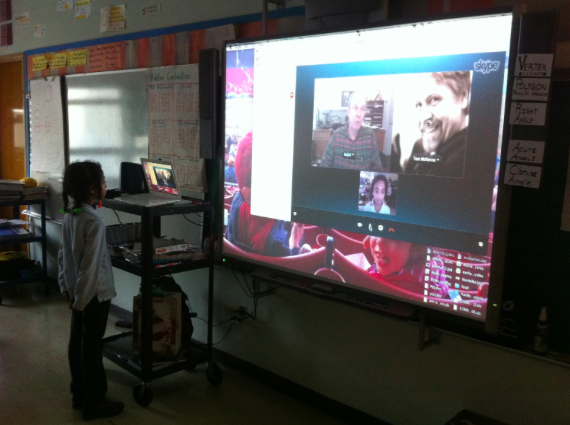

A Boston student speaks to Ralph Fletcher in a Skype session that served as the culmination of a mostly text-based exchange.

Often students would draft their pieces on paper and transfer to digital text. The initial questions directed to us would not be the mundane ones like “How do I start?” or “I don’t know what to write.” They knew what they wanted to write and were eager to begin. The questions were usually more “How do you spell . . . ?” or “Do I need a capital letter here?” Often, during initial drafts, both of us tended to downplay these questions and asked students to first just commit words onto paper. However, both of us noticed versions of Brendan’s observation. “When they would go to the computers, the students were not procrastinating with convention questions; they were viewing their words as a reflection of themselves and wanted these words to speak to who they were as a person and scholar. I remember students writing the term from the text, ‘Yidda-Yadda.’ After typing, many were confused why there still would be a red line under the word and shout, ‘BUT, IT’S STILL RED!’ as if petrified to move on knowing there was a mistake being made.”

One of Brendan’s students, Angeliah, noticed changes in her writing by the end of the year.

“At the beginning of the year when I was just writing with Jade I was really nervous . . . After I started writing with you two, I really started some skills like not writing ‘and’ so much and not saying ‘I’ so much.”

By rising to the challenge of representing themselves with the written word, students were able to take a hard look at themselves as writers and progress from young, run-on-sentence-wielding, assignment-satisfying, eight-year-old writers to more competent and reflective children of letters.

Category BLTN Teachers, Fall 2014 | Tags:

Leave a Reply