Interpretive Communities: Hayley Strandberg Takes Bread Loaf Class to Her Students

1September 15, 2012 by Tom McKenna

By Hayley Strandberg.

At Bread Loaf, students are challenged to enjoy, discover, and confront literature in all of its glorious possibility. We form communities at four different campuses with texts at the center. We create poems. We listen to arguments. We share stories over lunch. Imagine a place where readers around the world could do the same. The Interpretive Communities class at the Vermont campus in 2011 set out to create just such a space. With Dixie Goswami and Shel Sax at the helm, we went digital. With links to the original Bread Loaf course work, this piece chronicles my learning as I applied the concept of digitally-hosted interpretive communities to my own teaching.

Interpretive Communities:

A Year of Creating, Learning, and Making Mistakes

I teach A.P. Language and Composition at an all-girls Catholic high school in Concord, California. When the school decided to implement a “bring your own device” program, I knew it was time to make the leap and go digital.

A.P. Language and Composition, an 11th grade course at my school, requires students to read and respond to contemporary American non-fiction. My students read non-fiction primarily from the Modern American Prose anthology. I decided that asking my students to create text-centered websites to engage each other was the best way to engage them with the texts we were studying. I called these websites “interpretive communities.”

Modeled on and inspired by a summer 2011 class at the Bread Loaf School of English, I eagerly developed the assignment . (For my final course project, I blogged extensively about my experience in as a student.)

An interpretive community as an online space that is collaborative, text-centered, and interactive. It invites listening and storytelling.

I grouped my students based on their author preferences (2-4 to a group) and asked each group to focus its interpretive community on a single essay by an assigned author. In the second semester, these interpretive communities would guide our class readings of the essays in Modern American Prose. In this sense, my students were writing their own curriculum.

My students decided that in order to create effective interpretive communities they needed to know their audience: each other.

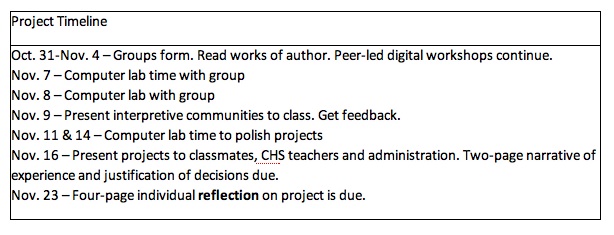

They developed a survey to learn about each other’s literacy habits and preferences. This survey was written by students and published on Survey Monkey. The survey results were published on the class website. These results, the class agreed, would be important as they created their interpretive communities. Students, for example, asked, “What is your favorite genre?” and “Do you have a Facebook account?” They weren’t always sure how the answers would inform their interpretive communities, but they knew that the more they knew about each other as readers and writers, the more likely they were to create engaging, student-friendly sites. (Please see figure 1 for the project timeline.)

Prior to formally beginning the assignment, I allowed three class periods in October for “digital tools” workshops. After my own Interpretive Community experience, I determined that the three most essential tools students would need to build their interpretive communities would be Google Sites, Blogger and PhotoStory (my school uses PCs primarily). Two workshops (Google sites and Blogger) were led by students familiar with the tools. I led a workshop on using PhotoStory since none of my students identified themselves as proficient in the program. After these workshops, I dedicated three weeks to the project:

Figure 1

Throughout the process, I viewed my role not as someone who had a lot of answers, but as someone who asked a lot of questions. How does that image relate to the text at the center of your online community? How are you allowing your audience to interact with that passage? Does that layout invite readers to share? I was able to question the class most formally on the November 9 class in which students presented their preliminary work. Students were also able to respond to each other’s work. At first, many were timid to present their work so openly out of fear that their “ideas might get stolen.” As soon as this fear was acknowledged and students had the opportunity to discuss the value of sharing and collaborating in life, they were able to share and move forward with each other more comfortably.

As the November 16 presentation neared, however, new fears surfaced. How do we know we’ve done this correctly? We’re not sure what you’re expecting. I asked students to have faith in the process and to re-read the assignment expectations on the written assignment. In truth, I, too, was unsure what their final product would look like. I had imagined it would look something like the Home Elsewhere interpretive community I had developed at Bread Loaf over the summer and had shared with them as a sample. But I knew, as they knew, that I had given them far more creative license with this project than with any other assignment. I, too, was learning what this product “should” look like as the interpretive communities were revealed to me by my students.

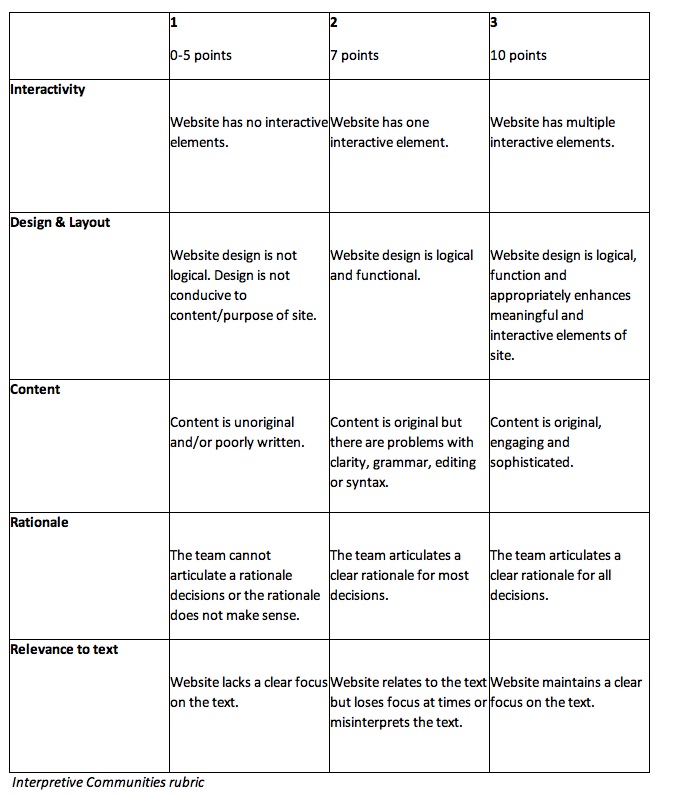

My philosophical focus on process over product and values (collaboration, engagement, interactivity) over tasks was also causing some anxiety since I had no formal rubric and students were unsure how the interpretive community itself would be graded. Though this focus naturally causes some anxiety, its reward is something much greater: creative liberty. In her final reflection, one student wrote: “It was not just a project with a checklist of things that our teacher wanted us to complete; it was a project that was entirely ours.” Nonetheless, in response to student concerns and after evaluating the final student product, I developed a working rubric that I hope will clarify expectations and grading in the future.

The interpretive communities “went live” to an audience of students, the Assistant Principal, Librarian, and Director of Technology. Each group gave a 7-minute presentation of their interpretive community which was followed by a 3-minute question-and-response session. By the end of the 80-minute class period, all 11th grade students had formally presented a text-centered website they had built and developed with and for each other. Random House and Google, watch out!

All interpretive communities were indexed into a single Google site “file cabinet” for each of the two classes by the school librarian. Each file cabinet linked to an interpretive community focused on a text by the author indicated on the cabinet. This was a great way to bring together all of the communities for both practical and visual purposes. In the second semester when students had to access these sites to respond to reading, they would know exactly where to go.

Interpretive Communities: Three Profiles

Students developed effective interpretive communities to varying degrees. Though the process of creating an interpretive community was an inherently engaging process for students–they were forced to learn new skills, interact with each other, and creatively respond to a text–students struggled to create a site that created the same experience for other readers. In getting caught up in their own composition process, students frequently got caught up in creating things like author bios and essay summaries instead of creating communities that engaged their readers through interactive elements. Admittedly, the standard I set was extremely high. To expect students to have developed an interactive game or iPhone app in their first interpretive community experience would have been unrealistic. For most students, learning how to compose in GoogleSites, Blogger and PhotoStory was challenge enough. Though the design and implementation of the interactive element was the most challenging aspect of the assignment for students, I’m proud to say that each interpretive community developed had at least one interactive element that explicitly elicited reader response. Often, this interactivity was in the form of a discussion board.

Profile #1 The White Album and “Why I Write” by Joan Didion

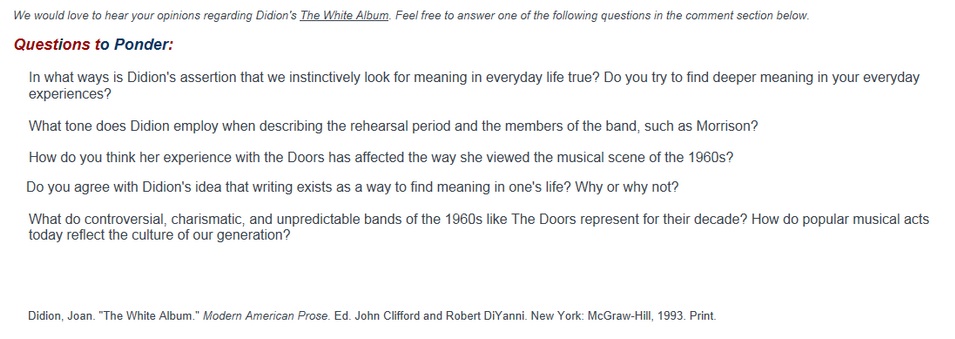

Alyssa and Dayna created an interpretive community centered on two of Joan Didion’s essays: The White Album and “Why I Write.” They used a Google Site to engage readers. From a Didion-focused homepage, their site has two links, each focused on a different Didion essay.

On their White Album page, the students included a link to the Doors’ music. They compiled relevant terms and resources. In comments on the discussion board, students noted how these elements allowed them to better understand Didion’s essay.

Finally, they left students with five questions to consider. They were invited to respond in writing on a discussion board, as illustrated below.

When the class read The White Album in the second semester, I required students to respond to these questions prior to an in-class discussion of the essay.

Responses to Dayna and Alyssa’s questions ranged from “I really enjoyed the questions to ponder segment” to “Didion picked the Doors as the icon of an attitude, instead of an age. I was intrigued by how she contrasted the sub-cultures of the sixties against each other.” The variety of responses speaks to students’ multiple levels of engagement with this project. In the first semester, students had been used to evaluating each other’s work. For this reason, it felt natural for Chloe W. to comment specifically about a particular element of the site. But in the second semester, they shifted from collaborative creators to engaged, interactive readers. We see this specifically in Shannon C.’s comment about The Doors as an “icon of an attitude.”

Dayna and Alyssa formatted their “Why I Write” page (in response to another Didion essay of the same name) in a similar fashion. It drew similar online response from the class. In their evaluation of the interpretive community, students responded with praised to its clean “Didionesque” style, and Alyssa and Dayna noted that they had designed the site with Didion’s aesthetic in mind. In a composition class that focuses primarily on how people write, I was thrilled that my students were considering design and visual rhetoric.

Profile #2 “The Ring of Time” by E.B. White

Jane, Megan, and Nicole’s group also used Google Sites to host their interpretive community on E.B. White’s essay “The Ring of Time.” Like Alyssa and Dayna, they included a discussion forum to engage the classmates in a discussion about the text.

Again, students responded enthusiastically and insightfully, though–usually–not directly to each other. For example, most students chose to respond to Discussion Question 3 about a single sentence from White’s essay: “She is at that enviable moment in life [I thought] when she believes she can go once around the ring, make one complete circuit, and at the end be exactly the same age as at the start.” Their responses, though thoughtful, tended not to acknowledge other responses. While the site–and the discussion question itself–are inherently valuable because they allowed students, in this case, to closely analyze the significance of a single sentence, the interpretive community showed no evidence of being interactive. Again, this was likely because I had not established the expectation that students contribute to the site multiple times or respond to each other’s prompts. Yet, participating on this forum allowed students to engage with the curriculum–if not always each other–before class. At the very least, students would interact with each other during class discussion. The interpretive community in all of its interactive shortcomings provided students an engaging place to write and think about what they read. This necessarily contributed positively to our class discussions.

In addition to the Discussion Forum, Jane’s group created a PhotoStory to engage students in “Ring of Time” before they read this essay.

In her final reflection on the project, Sydney C. wrote:

Seeing other students’ interpretive communities in class helped me understand how other people learn as well as how I learn. Since I am a visual learner, I found it fascinating viewing my classmate’s video trailers. Interpretive communities with movie trailers were the most successful because they provide a moving visual with sound and sometimes words that highlight the most exciting components of the story, rather than simple summary. One of the groups used a different type of program to make their community, and it was the best in the class because it had music, moving icons, and a movie trailer. – Sydney C.

This impressive “essay trailer” certainly got students’ attention, many commenting that this movie was particularly engaging and memorable.

Profile #3 – “Silence” by Maxine Hong Kingston

Sydney, Erika, and Morgan used Blogger to create their interpretive community on Kingston’s essay “Silence.” Their site included several interactive elements, such as a discussion forum and Google Map.

By including their own personal reflections, including one about the Chinese “I” versus the American “I,” this group welcomed others to share. They used GoogleMaps to chart the stories of immigrants and to invite readers to share their own:

The Google map was another thing that linked the world to the story. We all found several accounts from immigrants who struggled to fit in once they reached America. While looking for these stories I found it intriguing to read of all of the similar emotions that Kingston felt when she came to America. Viewers can add to the map so share their own story as well.

This group certainly succeeded in inviting storytelling. By asking readers to share their stories and by using a map to share the stories of immigrants to America, this group demonstrated a broad sense of community and a strong sense of the importance of storytelling. In response to a story about a young Chinese immigrant who becomes silent when pressured to speak English for the first time, this group acknowledges individual voice in all of the right ways. Their inviting and democratic interpretive community is a perfect companion to Kingston’s essay. Through its thoughtful design and content, this interpretive community is both empowered and empowering.

As I move forward with this project in the coming school year, I plan on using these models as prototypes for my current students. But interpretive communities are growing and changing spaces. I’m confident that my current students will bring their versions of these models to new and exciting places. I can’t wait to see where my students take their interpretive communities–and where those projects take my students–next.

Category Archives, BLTN Teachers, Fall-Winter 2012, Impacts | Tags:

Hayley, what wonderful work you’re doing carrying the digital communities into your AP classroom! Your analysis is thoughtful and includes worthwhile and professional criticism of the project. I especially like how you utilized your students’ work in the second semester by employing the interpretive communities again. It strikes me that when you use the student examples as part of the introduction, a discussion of how past students’ work has or has not been interactive in nature would help to define and focus future projects. I would very much enjoy a follow-up as this teaching method evolves with you and your students.