It is Presidents Day – a time to repost my traditional column commemorating the late, great Richard E. Neustadt. This year the post seems particularly timely, given the controversy surrounding our current President – especially the fear that his authoritarian tendencies will undermine the presidency and the Constitutional order. As I hope becomes clear by reading this post, I suspect Neustadt would have a different, but not less worrisome, reaction to Trump’s presidency.

Until his death in 2003 at the age of 84, Neustadt was the nation’s foremost presidency scholar. In his almost six decades of public service and in academia, Neustadt advised presidents of both parties and their aides, and distilled these experiences in the form of several influential books on presidential leadership and decisionmaking. Perhaps his biggest influence, however, came from the scores of students (including Al Gore) he mentored at Columbia and Harvard, many of whom went on to careers in public service. Others (like me!) opted for academia where they schooled subsequent generations of students in Neustadt’s teachings, (and sometimes wrote blogs on the side.)

Interestingly, Neustadt came to academia through a circuitous route that, unfortunately, is rarely used today. After a brief stint in FDR’s Office of Price Administration, followed by a tour in the military, he returned to government as a mid-level career bureaucrat in President Harry Truman’s Bureau of the Budget (BoB) in 1946, gradually working his way up the ranks until he was brought into Truman’s White House in 1950 as a junior-level political aide. While working in the BoB, Neustadt took time to complete his doctoral dissertation at Harvard (working from Washington), which analyzed the development of the president’s legislative program. When Truman decided not to run for reelection in 1952, Neustadt faced a career crossroads. With the doctorate in hand, he decided to try his hand at academia.

When he began working his way through the presidency literature to prepare to teach, however, he was struck by just how little these scholarly works had in common with his own experiences under Truman. They described the presidency in terms of its formal powers, as laid out in the Constitution and subsequent statute. To Neustadt, these formal powers – while not inconsequential – told only part of the story. To fully understand what made presidents more or less effective, one had to dig deeper to uncover the sources of the president’s power. With this motivation, he set down to write Presidential Power, which was first published in 1960 and went on to become the best-selling scholarly study of the presidency ever written. Now in its 4th edition, it continues to be assigned in college classrooms around the world (the Portuguese language edition came out a few years back.) Neustadt’s argument in Presidential Power is distinctive and I certainly can’t do justice to it here. But his essential point is that because presidents share power with other actors in the American political system, they can rarely get things done on a sustained basis through command or unilateral action. Instead, they need to persuade others that what the President wants done is what they should want done as well, but for their own political and personal interests. At the most fundamental level that means presidents must bargain. The most effective presidents, then, are those who understand the sources of their bargaining power, and take steps to nurture those sources.

By bargaining, however, Neustadt does not mean – contrary to what some of his critics have suggested – changing political actors’ minds. As I have written elsewhere, Neustadt does not mean that presidents rely on “charm or reasoned argument” to convince others to adopt his (someday her) point of view. With rare exceptions, presidential power is not the power to change minds. Instead, presidents must induce others “to believe that what he wants of them is what their own appraisal of their own responsibilities requires them to do in their interests, not his.” That process of persuasion, Neustadt suggests, “is bound to be more like collective bargaining than like a reasoned argument among philosopher kings.”

At its core, Presidential Power is a handbook for presidents (and their advisers). It teaches them how to gain, nurture and exercise power. Beyond the subject matter, however, what makes Neustadt’s analysis so fascinating are the illustrations he brings to bear, many drawn from his own personal experiences as an adviser to presidents. Interestingly, the book might have languished on bookstore shelves if not for a fortuitous event: after his election to the presidency in 1960, President-elect John F. Kennedy asked Neustadt to write transition memos to help prepare him for office. More importantly for the sale of Neustadt’s book, however, the president-elect was photographed disembarking from a plane with a copy of Presidential Power clearly visible in his jacket pocket. Believe me, nothing boosts the sale of a book on the presidency more than a picture of the President reading that book! (Which reminds me: if you need lessons about leading during a time of crisis, President Trump, I’d recommend this book. Don’t forget to get photographed while reading it!)

But it takes more than a president’s endorsement to turn a book into a classic, one that continues to get assigned in presidency courses today, more than two decades after the last edition was issued. What explains Presidential Power’s staying power? As I have argued elsewhere, Neustadt’s classic work endures because it analyzes the presidency institutionally; presidential power, according to Neustadt, is primarily a function of the Constitutionally-based system of separated institutions sharing power. That Constitutional grounding makes Neustadt’s analysis of continuing relevance. And while many subsequent scholars have sought to replace Neustadt’s analysis with one of their own, for the most part they end up making his same points (although they often don’t acknowledge as much) but not nearly as effectively.

Neustadt was subsequently asked to join Kennedy’s White House staff but – with two growing children whom had already endured his absences in his previous White House stint – he opted instead to stay in academia. He went on to help establish Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, wrote several more award-winning books, and continued to advise formally or informally every president through Clinton. After the death of Bert, his first wife, he married Shirley Williams, one of the founders of Britain’s Social Democrats Party (and now a Baroness in the House of Lords), which provided still another perspective on executive politics. He also continued churning out graduate students (I was the last doctoral student whose dissertation committee Neustadt chaired at Harvard.). When I went back to Harvard in 1993 as an assistant professor, my education continued; I lured Neustadt out of retirement to co-teach a graduate seminar on the presidency – an experience that deepened my understanding of the office and taught me to appreciate good scotch. It was the last course Neustadt taught in Harvard’s Government Department, but he remained active in public life even after retiring from teaching. Shortly before his death he traveled to Brazil to advise that country’s newly-elected president Lula da Silva.

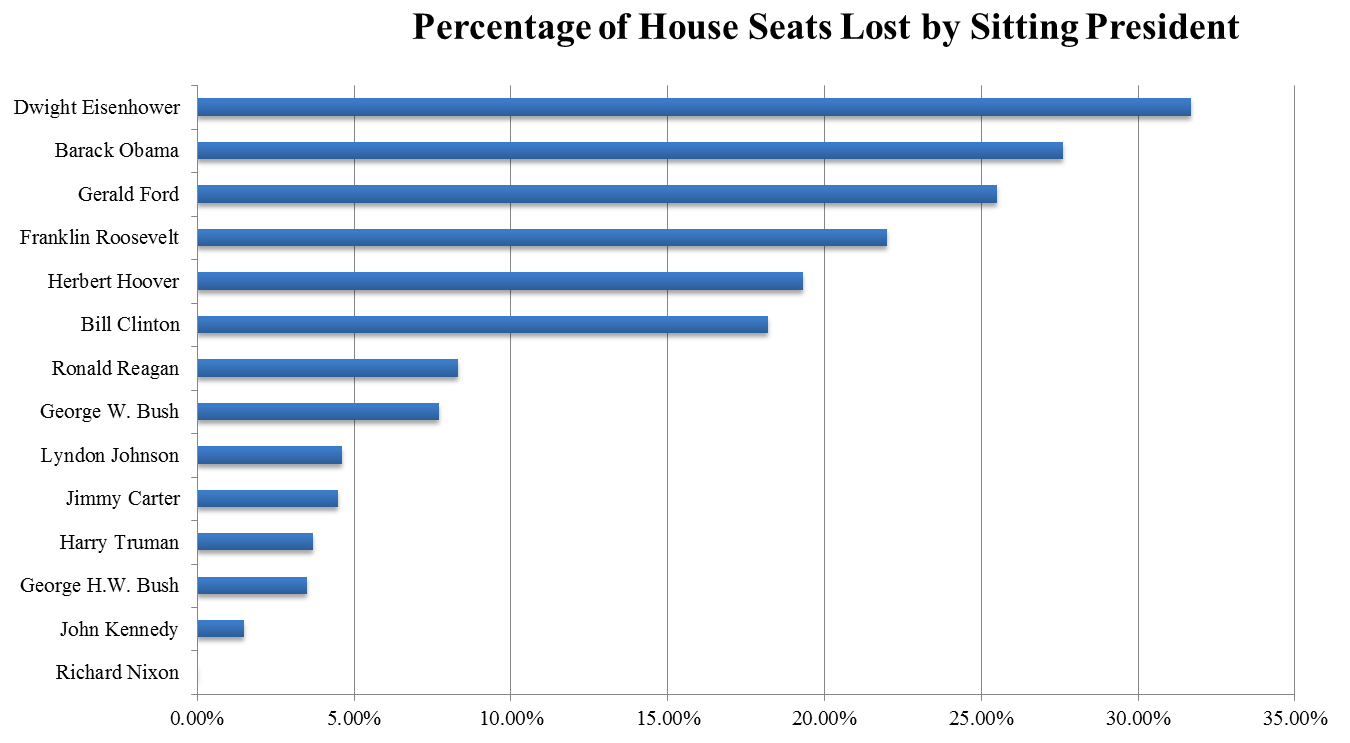

What might Neustadt make of the Trump presidency? That is a topic worthy of a separate post. But I suspect that in contrast to many of my political science peers, who have expressed a fear that Trump’s authoritarian tendencies pose a threat to the Constitutional order, Neustadt would have a different concern: that Trump’s inexperience – compounded by his initial decision to surround himself with equally inexperienced aides – has led to an exceptionally weak presidency, one unable to provide the energy and institutional stiffening that Neustadt believed was indispensable for making our system of shared powers work toward solving national problems. To be sure, that weakness might yet lead a frustrated president to lash out against his political enemies, and to engage in extraconstitutional actions that could further weaken the presidential office. If so, my colleagues’ fears may yet be realized. For now, however, I suspect Neustadt would worry not that Trump’s presidency was too powerful – but that it was not powerful enough.

In the meantime, take time today to hoist a glass of your favorite beverage in honor of Richard E. Neustadt, our own Guardian of the Presidency. If you are interested in learning more about him, there’s a wonderful (really!) book available on Amazon.com edited by Neustadt’s daughter and that blogger guy from Middlebury College (see here). It contains contributions from Doris Kearns Goodwin, Al Gore, Ernie May, Graham Allison, Ted Sorensen, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., Harrison Wellford, Harvey Fineberg, Jonathan Alter, Chuck Jones, Eric Redman, Beth Neustadt and yours truly.

Here’s to you, Dick!