So, what explains the Supreme Court’s decision to uphold the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, more popularly known as Obamacare? As most of you will recall, I thought the justices’ votes would fall largely along ideological lines, as captured by a short-hand measure – whether the justice was nominated by a Republican or Democratic president. My back-of-the-envelope reasoning was based on more sophisticated models developed by legal scholars regarding how justices make decisions. Based on my reading of this “attitudinal” model, I anticipated a five-to-four decision rejecting the argument that the mandate fell under the umbrella of the interstate commerce clause. The government, in fact, cannot make you eat broccoli. And that is precisely what happened – the Court’s Republican appointees ruled as a bloc against the Democrats to say the mandate was not permissible under the interstate commerce clause. Here’s the key section, written by Chief Justice John Roberts, from the Supreme Court’s health are ruling:

“The individual mandate, however, does not regulate existing commercial activity. It instead compels individuals to become active in commerce by purchasing a product, on the ground that their failure to do so affects interstate commerce. Construing the Commerce Clause to permit Congress to regulate individuals precisely because they are doing nothing would open a new and potentially vast domain to congressional authority. “

This extends a series of Supreme Court rulings dating back to the Rehnquist court in which a majority of the justices have begun to put limits on an expansive reading of the interstate commerce clause. So far, so good for the attitudinal model.

What I did not anticipate, however, was Roberts’ then joining the four Democratic-nominated justices to uphold the mandate under Congress’ taxing power. Granted, I’m no legal scholar, and this is a blog about the presidency, but I don’t recall too many legal experts who saw this twist coming either. Roberts, now aligned with the four Democratic court nominees, writes:

“Sustaining the mandate as a tax depends only on whether Congress has properly exercised its taxing power to encourage purchasing health insurance, not whether it can. Upholding the individual mandate under the Taxing Clause thus does not recognize any new federal power. It determines that Congress has used an existing one.”

To justify this ruling and mollify conservatives, Roberts’ claims a distinction between Congress’ power to regulate interstate commerce clause and Congress’ taxing power, namely that the power to tax does not give Congress the same degree of control over individuals as does the power to regulate commerce:

“Third, although the breadth of Congress’s power to tax is greater than its power to regulate commerce, the taxing power does not give Congress the same degree of control over individual behavior. Once we recognize that Congress may regulate a particular decision under the Commerce Clause, the Federal Government can bring its full weight to bear. Congress may simply command individuals to do as it directs. An individual who disobeys may be subjected to criminal sanctions. Those sanctions can include not only fines and imprisonment, but all the attendant consequences of being branded a criminal: deprivation of otherwise protected civil rights, such as the right to bear arms or vote in elections; loss of employment opportunities; social stigma; and severe disabilities in other controversies, such as custody or immigration disputes. By contrast, Congress’s authority under the taxing power is limited to requiring an individual to pay money into the Federal Treasury, no more. If a tax is properly paid, the Government has no power to compel or punish individuals subject to it.”

I will leave it to legal scholars to parse the relative impact of the power to regulate commerce versus the power to tax. But the practical implications of Roberts’ ruling are the same: the mandate survives and the health care law is essentially intact. (To be sure, the Court also struck down, by a 7-2 margin, with justices Elena Kagan and Stephen Breyer joining the Republican voting bloc, the Medicaid extension portion of Obamacare. The majority ruled that the federal government could not take away all of a state’s Medicaid money if the state does not agree to the Medicaid extensions mandated by Obamacare. Practically speaking, I’m not sure what effect this will have, since it is hard to believe states will turn down federal monies, but it does strike another blow, legally speaking, for federalism.)

So, the question becomes: what motivated Roberts to side with the four Democratic justices and uphold the mandate? One answer, of course, is that he buys his own argument that the penalty provision of the mandate is really a tax, and thus perfectly permissible under the Constitution. Never mind that when enacting the law Congress did not call it a tax and that the Obama administration, for the most part, studiously avoided using that term. Roberts ruled, essentially, that if it walks and quacks like a tax, it is a tax.

The problem I have with this argument is that the other Republican justices did not accept Roberts’ reasoning; they argue, in their dissent, that it is a penalty, not a tax, and that the two are not the same. Note that the dissenters include Justice Kennedy who, according to the attitudinal model, would typically vote similarly to Roberts. But not this time. In their dissent, the Republican justices write:

“The Government contends, however, as expressed in the caption to Part II of its brief, that “THE MINIMUM COVERAGE PROVISION IS INDEPENDENTLY AUTHORIZED BY CONGRESS’S TAXING POWER.” Petitioners’ Minimum Coverage Brief 52. The phrase “independently authorized” suggests the existence of a creature never hitherto seen in the United States Reports: A penalty for constitutional purposes that is also a tax for constitutional purposes. In all our cases the two are mutually exclusive. The provision challenged under the Constitution is either a penalty or else a tax. Of course in many cases what was a regulatory mandate enforced by a penalty could have been imposed as a tax upon permissible action; or what was imposed as a tax upon permissible action could have been a regulatory mandate enforced by a penalty. But we know of no case, and the Government cites none, in which the imposition was, for constitutional purposes, both. The two are mutually exclusive. Thus, what the Government’s caption should have read was “ALTERNATIVELY, THE MINIMUM COVERAGE PROVISION IS NOT A MANDATE-WITH-PENALTY BUT A TAX.” It is important to bear this in mind in evaluating the tax argument of the Government and of those who support it: The issue is not whether Congress had the power to frame the minimum-coverage provision as a tax, but whether it did so.”

What, then, explains Roberts’ ruling, if not the attitudinal model? As I tweeted yesterday, I think the answer lies in his position as Chief Justice. Roberts, in my view, was thinking institutionally when he decided to uphold the mandate. That is, he was careful in making his ruling to protect the Court’s autonomy and future power prospects. As Chief Justice he has greater stake than his colleagues in maintaining the Court’s reputation for impartiality. In this sense, Roberts was motivated by the same sentiments that guided John Marshall in the celebrated Marbury v. Madison case: the need to protect the Court’s institutional interests. Remember, the power of the Court rests on the degree to which other actors, and the public view its decisions as legitimate – that is, not motivated by purely partisan reasoning. By upholding the mandate, and thus leaving Obamacare reasonably intact, Roberts protected the Court’s institutional interests. It is also the case, however, that once we dig beneath the obvious implications of this ruling – that Obamacare survives – there is much in the ruling that conservatives can like, beginning with the limits on the extension of Medicaid. In terms of legal doctrine, Roberts’ reasoning appears, at least in theory, to reduce the scope of Congress’ use of the interstate commerce clause and spending power as a means of enacting social welfare measures, although the practical implications of this can be debated. And, of course, by labeling the penalty a “tax”, Roberts has handed the Republicans a political sword which they can use in their effort to repeal the bill, and to attack Obama in the general election campaign. So this was not an unalloyed victory for the President or his party. On the whole, however, it certainly was better for them than the alternative: striking the bill down in its entirety.

The broader lesson, and one that I did not fully appreciate in thinking about how the Court would rule, is that justices are free to vote their beliefs as long as they are not subject to conflicting constraints. In this case, I think Roberts’ role as Chief Justice, and his desire to keep the Court from appear overtly partisan, overruled his ideological preference, which was to strike the mandate down in its entirety. In so doing, however, he has better positioned the Court’s conservative majority to pursue its ideological preferences in future cases.

3:17 p.m. Charles Krauthammer makes essentially the same argument in this op ed piece. (Thanks to George Altshuler for the link to Krauthammer’s piece.)

And here’s the Senate seats lost:

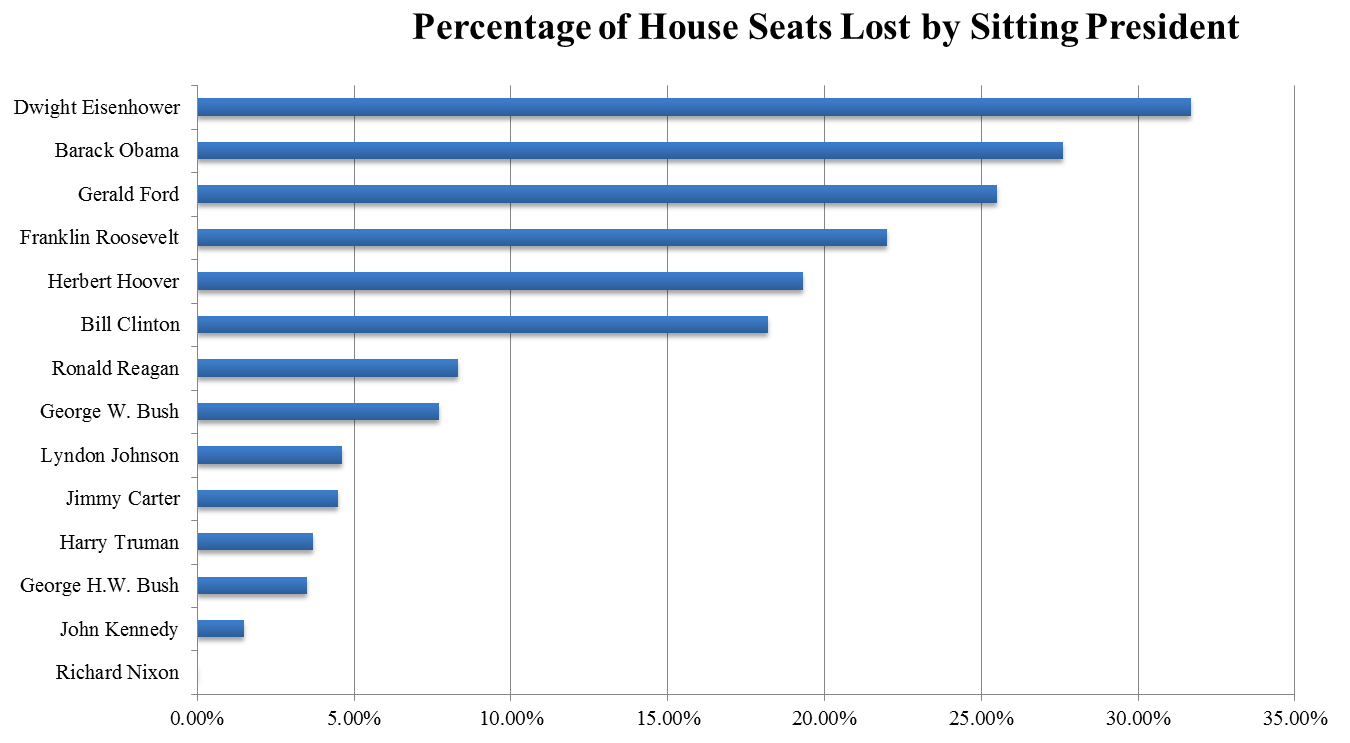

And here’s the Senate seats lost: Clearly Obama has been an equal opportunity president.

Clearly Obama has been an equal opportunity president.