Organizing Youth Voice when the Stakes are High

0June 3, 2022 by Cole Moran

In December of this year, my students and I were made aware of an “innovation proposal” that would close our public, open-enrollment high school and re-open it beholden to a private board. The “innovation school” process takes advantage of a curious loophole in Massachusetts state law that allows any parent, teacher, or organization related to education to apply for an innovation school. Notably, students are not allowed to be applicants. I wrote at length about my colleague’s and my qualms with the innovation prospectus in The Boston Globe. The most glaring issue: student voice was completely absent from the process.

To be clear, Charlestown High School is in need of change and innovation (I’d argue, quite unoriginally, that we need to rethink higher schooling altogether). Our enrollment is down, we have high rates of chronic absenteeism, and students feel that our school doesn’t always meet their needs. What I noticed happening, though, was that adults began to line up on each “side” of this debate. One side (myself included) defended our high school vigorously, accurately pointing out that our status as a “failing” school is, in many ways, absurd. Just a small example: 17% of our student population have significant disabilities and IEPs that legally require they receive services until they are 22; these students count “against” us in our four-year graduation rate. We don’t drop students from our rolls when they are housing unstable, we take students mid-year after they are pushed out of the area charter schools, and we have an overrepresentation of every group of student you can imagine who needs greater support. We’re dinged for all of these things. And we know there is no magic bullet: A whopping 0% of our English Language Learners demonstrated proficiency on our statewide Grade 10 ELA test (MCAS). But, only 4% of ELs statewide do so. We want better tools to genuinely measure how we are educating and supporting our students compared to their peers across the state.

On the other side of this debate, parents, mostly of younger children in the district, had major concerns about the outcomes for students at our school. They, accurately, pointed out that many of our students are not college and career ready when they graduate from our high school. They pointed to years of declining data that, while confounded somewhat by COVID, speaks to an underlying reality: fewer and fewer students are choosing to attend our school.

On each of these sides, I saw people who cared deeply about the outcomes of children in the Boston Public Schools. Curiously, neither of us thought to ask students what they thought. So, that’s what we did!

When the prospectus dropped, I asked students what they thought of it. The lesson is detailed here. We condensed the prospectus into factual bullet points and asked students to highlight things they liked, things they had questions about or needed more information on, and things they did not like. This lesson sparked generative conversations about what students perceived as a gap between the prospectus authors and their own lived experience. Students appreciated options like a terminal associate’s degree or certificate upon graduating, and better lunch options through a partnership with Boston-based MyWayCafe. But, they felt like the extended school day, even with built-in internship and work options, didn’t take into account their roles as care-takers at homes, and they had more than a few “show me the money!” moments. Students also questioned who was behind the proposal. They felt that guaranteed pathways from three neighborhood schools (which are the three lower schools with the highest proportion of white students in the district) amounted to an attempt to “gentrify our school” which serves 95% students of color.

But what if it didn’t have to be so black and white? What if students could lead their own innovation process?

After thoughtfully analyzing each aspect of the prospectus, students prepared testimony for the school committee and made their voices heard in the media. The innovation proposal was ultimately rejected by the screening committee. One of the key reasons the committee cited was a lack of community–and particularly, student–engagement in the innovation proposal process. It was a victory, but perhaps a pyrrhic one. Many of the ideas in the proposal were strong, and appear to have withered within the staid bureaucracy of the Boston Public Schools. But what if it didn’t have to be so black and white? What if students could lead their own innovation process?

“It was a different experience and different from any other school project. It gave us the opportunity to use our ideas and take them to another level, also sharing them with peers and hearing their ideas, teaching us how much power we can have and getting out of our comfort zone with this project.” —Juliana Pulido Duque

“I think student voices are very important resources that no one ever uses. I think it’s best to hear directly from students who attend these schools and experience the effects from the choices adults make. And what I enjoyed the most about the project was our voices actually being heard and realizing that people care about our opinions and ideas.” —Ashantii Person

These questions led us to develop a week-long course called Rethinking Higher Schooling that we offered over February vacation. Twenty-one students attended, divided into small groups, and developed designs for the future of Charlestown High School. They then presented their designs to the BPS Chief of Schools and our regional superintendent. They’d made their voices heard again, and saw adults who deeply believed in their mission. But, institutions can be slow to change and there seemed to be no clear path to enacting the designs. Some students became discouraged. For others, this simply mirrored many other “authentic” learning tasks (e.g., write a letter to the mayor that isn’t read, write an op-ed that isn’t published, etc.). We’re combatting years of showing our students we won’t change, in time for them.

“I enjoyed listening to other people’s ideas. I was like ‘Wow, I never really thought of that. I should include that into my idea of the school.’ Just seeing everyone come together showed me that we have similar ideas about what to change….It felt great. Not only was the proposal shot down, people were willing to hear what we wanted to see in the school.” — Leidy Cruz

An antidote to this mood? We simply doubled down and got more students involved. After students took their state test (the MCAS), we engaged in the same design process with the rest of the 10th grade. Students again split into groups and designed the future of schooling at Charlestown High School.

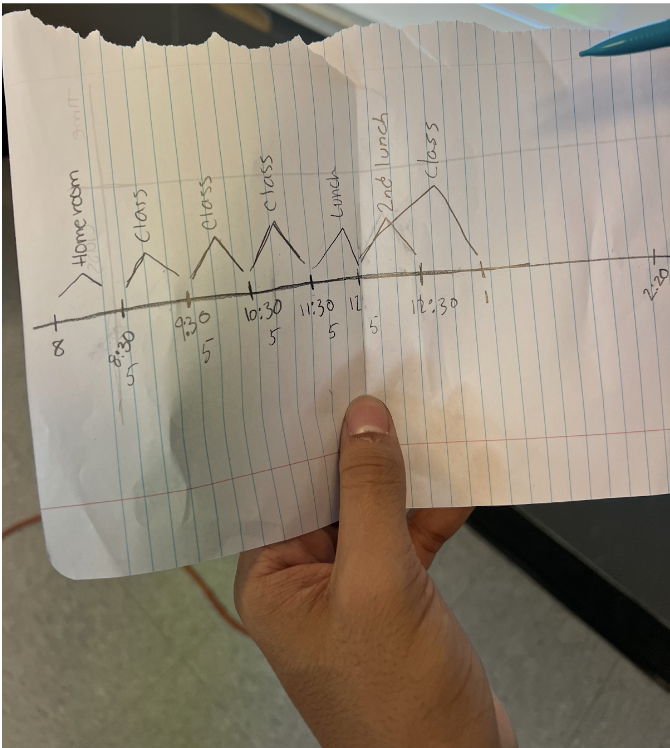

Groups crafted a vision statement, schedule, program of study, safety and conflict resolution plan, extracurricular programming, partnerships plan, and staffing plan. Most commonly, students demanded more appealing food options, later start times (we start at 7:30 and the average transit time for a student is one hour), more course options, increased vocational/dual-enrollment choices, and more teachers of color. Some unique ideas included a “one-at-a-time” course schedule similar to Colorado College, a swipe ID system to foster a safe open campus policy, and a four-day week in which the fifth day emphasizes personalized learning.

“This process really opened my eyes to the areas of the school that could be improved (middle school, high school, education for students with disabilities). It opened my mind about special education. I didn’t realize that the school is not accessible for everyone. Every part of the school needs assistance and to be upgraded. For everything I thought of, there was another thing to work on.” —Leidy

“We knew that [the innovation proposal] was about gentrification. When we pass one of them on the sidewalk walking their little dogs, those people, mostly white, will cross over to the other side. They don’t want to share the neighborhood with us.” —Mariaelena Suazo

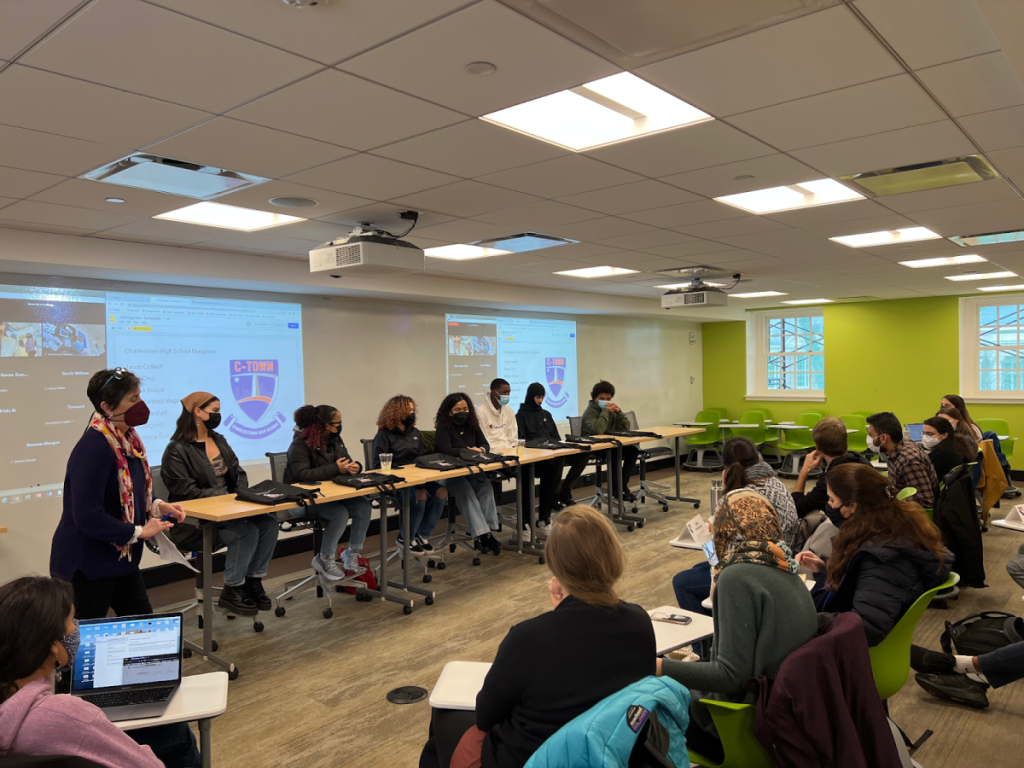

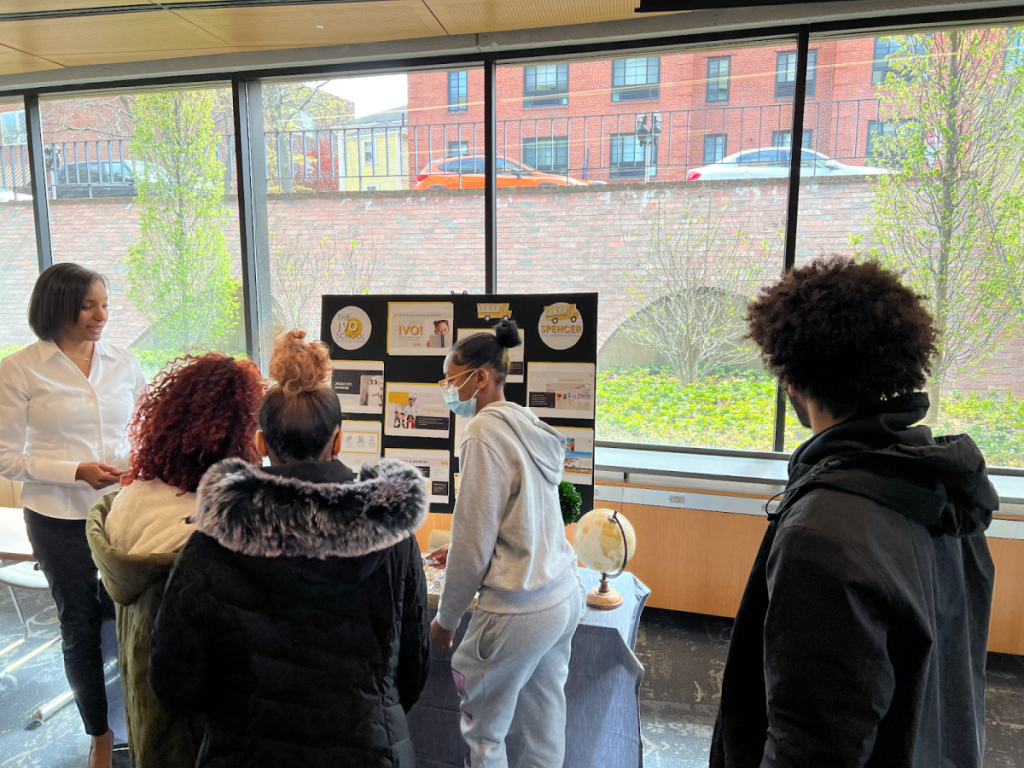

Seven students were invited to present their designs at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Linda Nathan, a professor at HGSE and founding principal of Boston Arts Academy and Fenway High School, innovative schools in the Boston Public Schools, teaches a course there on school design. She wanted her students, school leaders from across the globe, to learn from Charlestown youth. Our students were able to make deep connections with the graduate students, and many of their design ideas influenced these future global schools.

“Going to Harvard was dope! I really liked being able to present to them, know that they took our ideas into consideration, and then getting to see that they implemented some of our feedback was really cool. There was a school that was see through. She had different departments for each part of the school but they could come together in the center. She was big on inclusivity.” —Leidy

“It was nerve wracking at first, but once I got comfortable with the setting I was in, I felt like I was making a change and a difference.”— Mariaelena

I believe deeply in rethinking higher schooling. But, tangible change often feels a long way off for students. Partly to show skin in the game, and partly because I’m curious how it will go, I told students they could use “my” 75 minutes per day however they wanted for the rest of the year, as long as it was dedicated to learning something within the English Language Arts. This is a small way to give students space to implement some of their own ideas for how they’d direct their “higher schooling.”

Students are embarking on “passion projects” for the rest of the year. The only requirement? They have to read 25,000 words (ish) and write 1500 words (ish). Student ideas have come up with rich ideas and beautiful concepts: a short film on the coming out experiences of LGBTQ+ youth at Charlestown, a cultural critique of the white-washing of Mitski, an essay on “Appropriation vs. Appreciation” of Black culture, and a deep-dive on intergenerational trauma in Latinx communities.

The next steps are unclear. I am on an “intervention team” that will make recommendations to the superintendent for the best path forward. Student ideas (including an altered schedule, increased choice in the program of study, and more vocational options) have risen to the fore. But, it still feels uncertain. While this can be a moment of frustration, it has also been a powerful teaching moment that “power concedes nothing without a demand.” Students have seen first-hand, especially through the relationships they’ve built with HGSE staff and students, how powerful and impactful their ideas are. They’ve also seen the frustration of being stymied by institutional inertia. We remain hopeful that this “intervention team” can deliver on the demands of young people. And if they don’t, we will re-organize and continue to make youth demands heard loudly until Charlestown High School is the school our students deserve.

Cole Moran is a 2021-22 Charles M. Gately ’62 Family Fellow.

Category BLTN and Policy, Featured, Spring / Summer 2022 | Tags:

Leave a Reply