“Greece and, in Greece, the Parthenon have marked the apogee of this pure creation of the mind.”

Le Corbusier, Towards a New Architecture (1923)

At the beginning of the twentieth century, modernist architects and artists sought to retrieve a pure, abstract essence of form and structure in their works. Some of them recognized these rational qualities in the stark Doric and elegant Ionic forms of the High Classical Periclean monuments on the Athenian Acropolis.

In 1911, Jean-Eduard Jeanneret (French, born Switzerland, 1887-1965), the architect better known as Le Corbusier, visited Athens as part of his pivotal “Journey to the East.” His first-hand exposure to the Periclean monuments led him to become an architect. With his pioneering modernist buildings, he categorically rejected a revivalist style, but his works are clearly informed by an appreciation for the classical monuments he saw.

The crisp forms of the Acropolis ruins remain a profound source of inspiration for generations of modernist architects, artists, photographers, and choreographers alike. Many of them visited the Acropolis, opened their sketchbooks or set up their easels and cameras, and found inspiration for their own versions of what they hoped to be timeless artistic expression.

(PA) (NA)

Le Corbusier-Saugnier (Charles-Eduard Jeanneret, Swiss, 1887–1965) and Amédée Ozenfant (French, 1886–1966)

Vers une architecture [Towards a New Architecture], 1923 (first edition), pg. 106–107

Special Collections

In May 1911, Le Corbusier set off from Berlin on a five-month trip that took him to the Balkans, Istanbul, Greece, and Italy. It exposed him to the vernacular architectures and the monumental structures that would inspire him for his entire career. The ideas he developed were published in his 1923 book Vers une architecture [Towards a New Architecture], arguably the most important manifesto of modernist architecture.

In the section entitled “Architecture, Pure Creation of the Mind,” Le Corbusier pairs photographs of ancient Greek temples (the archaic Temple of Hera at Paestum, Italy; the High Classical Parthenon in Athens) with images of contemporary cars (a Humbert from 1907; a Delage “Grand-Sport” from 1921) as a way of underscoring how the ancient structures developed into types that got ever closer to “a state of perfection universally felt.”

(PA)

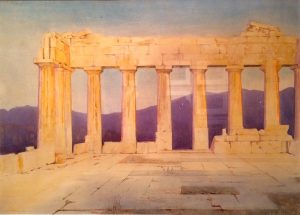

Johanna Magdalene Boericke (American, 1868–1949)

The Parthenon Columns at Sunset, c. 1910

Watercolor

Private Collection

A spirited native of Philadelphia and a student at the Pennsylvania Academic of Fine Arts, Johanna Boericke studied watercolor painting in Rome in 1907. Before departing for Paris to take up portraiture, she traveled to Greece with her friend and fellow artist Paula Himmelsbach Balano (1877-1967).

In this watercolor Boericke shows the interior of the Parthenon looking out towards the east in a stark but carefully balanced composition. The outline of Mount Hymettus in the distance lyrically interacts with the temple’s regimented colonnade.

This painting was exhibited in 1915 in Rochester, New York. Later in life, Boericke became the president of the Plastic Club, an art club in Philadelphia that still exists today.

(PA)

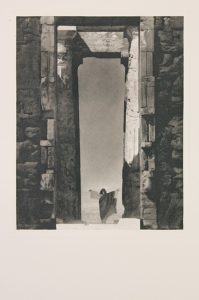

Edward Steichen (American, born Luxembourg, 1879–1973)

Isadora Duncan at the Portal of the Parthenon, Athens, 1920, printed 1981

Hand-pulled dust-grain photogravure

Object size: 20 x 16 inches

Purchase with funds provided by the Fine Arts Acquisition Fund

2015.225

In 1921 Edward Steichen followed the founder of Modern Dance Isadora Duncan (American, 1877–1927) to Greece after she promised to let him film her dancing. Once in Athens Duncan changed her mind because, as Steichen stated, “she didn’t want her dancing recorded in motion pictures but would rather have it remembered as legend.” Using a borrowed camera, he made a handful of photographs as she performed on the Periclean monuments.

This photograph is taken from the Parthenon’s interior looking out through its western doorway. Duncan, framed by the portico’s vast columns, strikes a commanding and expansive pose. Steichen commented: “Her whole art of dancing was inspired by the Greek architectural friezes and the drawings on Greek vases. She was a part of Greece, and she took Greece as a part of herself.”