Glen Ernstrom, Assistant Professor of Biology and Neuroscience, leading a workshop on POGIL (Process Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning)

What is POGIL?

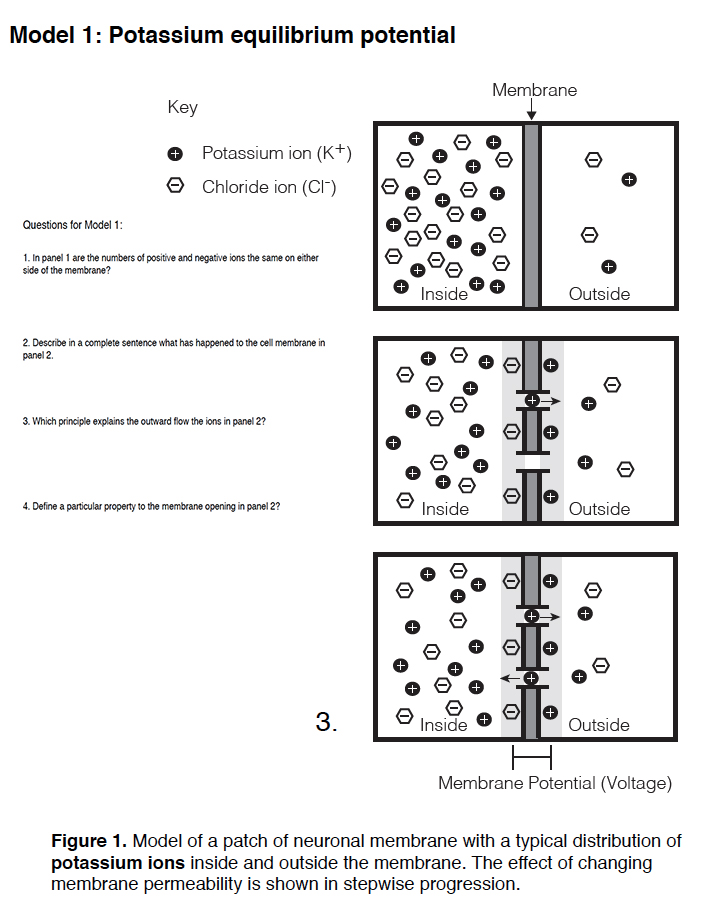

Glen: POGIL stands for Process-Oriented Guided Inquiry Learning. It’s a mouthful. It is a method of active learning that has two major foundations. One, to emphasize process, the idea of learning how to collaborate, how to do time management, gather resources, resolve problems, conflicts, or disagreements. That’s the process aspect of the learning process. The second foundation is guided inquiry learning. That’s where you deliver content in a way that students can access that content through an active learning process.

What do you mean by active learning?

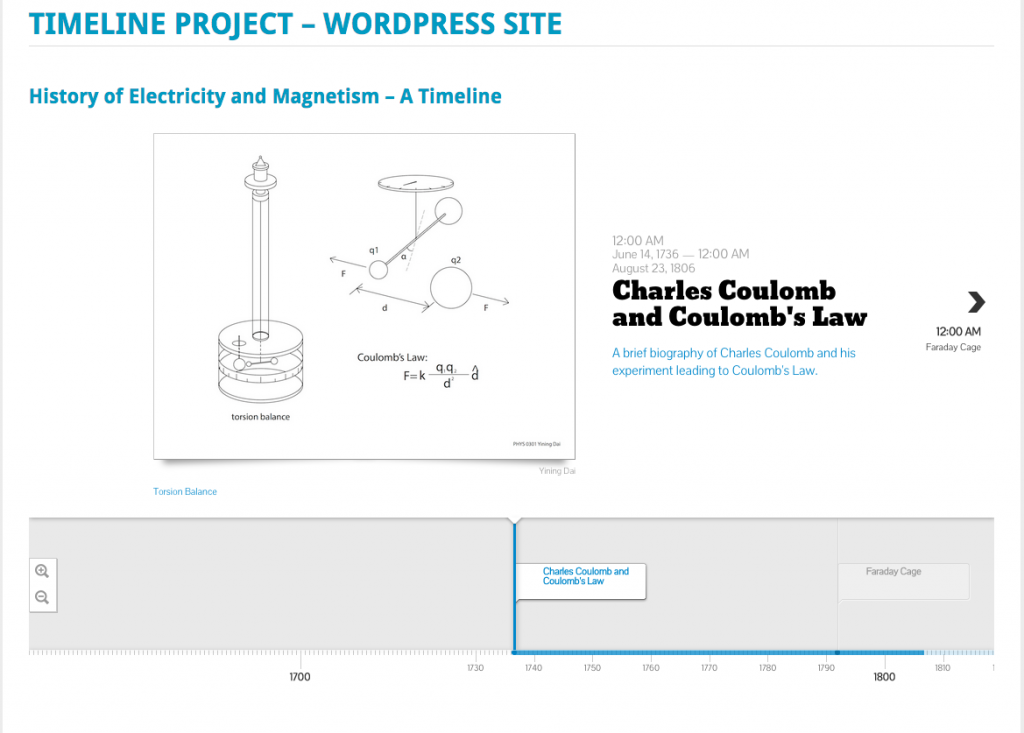

Glen: Active learning is a process where the students take control of their learning, and as the instructor, you provide resources that facilitate learning new content. As a teacher, you have to prepare materials ahead of time: a set of questions, a worksheet centered around a model, or a diagram where students can start to interrogate this model by defining terms and by working their way through a learning cycle process of basic definitions. Through some sort of evaluation, this brings them to a higher order of thinking that involves analysis and synthesis. It’s an interactive process within a typical class session. You might do two or three of these learning cycles, working through a set of questions on the order of ten questions per cycle, with each cycle lasting about fifteen minutes each.

How does this differ from traditional methods of instruction?

Glen: Students active formulate content by solving problems together in groups. The students interact with each other working on those process goals. An important characteristic of this type of active learning is that students work in groups of three to four, as they work together on these worksheets. Each person in the group has defined roles — a manager, a note-taker, an oral presenter, or a librarian — so you work on these process goals while at the same time learning the content. At the most basic level, it is a break from traditional passive instruction towards one where students are encouraged to take control of their own learning.

Why did you choose this to make this change in instructional method?

Glen: I am convinced by several studies that show positive learning outcomes from active learning activities like POGIL. Students retain the knowledge longer, and they enjoy the learning process better overall. People are also finding that underrepresented minorities perform better in classes with active learning.

What’s prevented you from doing nothing but POGIL?

Glen: There is student resistance. Not all students like the knowledge that they’re going to have to come to class prepared and to be able to exchange ideas, and that they’ll be assessed on that ability rather than just coming to class and passively sitting in a lecture hall. They realize that there’s more onus on them when with respect to class time. There’s resistance and sometimes some pushback on that. There’s also a very common report on course evaluations from some students who perceive this as the faculty not actually teaching. Even as this idea of active learning is trickling through our community, both from a faculty perspective and an administrative and student perspective, there’s still work that needs to be done for students to get used to it. So my approach has been to try to work it in into areas where the subject matter becomes especially tricky, more complex, and less straight-forward. That’s where POGIL really does a good job of reinforcing ideas and helping students really assess themselves. Do I really know this or not? Then by working in groups and comparing the results of their work in class, they can measure themselves with their peers and see how well they are in doing. They get immediate feedback on their understanding.

If you imagined a world in which the students saw the light and realized that this actually is a fabulous way for them to learn, could you imagine doing nothing but POGIL?

Glen: I think there needs to be a balance because people learn in different ways. Even for people that are really into active learning, I think balancing a traditional lecture format with POGIL would be effective. Early in the week, you set the stage and provide some factual content; later in the week you reinforce those new concepts with a POGIL activity. Despite the benefits and advantages of working together and doing these process activities, there are some people that just don’t work that well and find it hard to work in that situation. There still needs to be more studies on this. Because people learn in different ways, having both options available to people is the best route for me, at least right now. And maybe people will find that that’s the way to go.

How do you introduce POGIL into a class?

Glen: There are different thoughts on this. Do you explain the theory behind POGIL and explain what POGIL stands for, or do you just say, hey, we’re going to do some class activities to help reinforce this and let the structure teach itself rather than explaining and justifying it. These days students want to know that what we’re doing is useful and that there’s some science behind what we’re doing. That’s why I decided to introduce the term “POGIL,” and provided some literature about the method and I showed them graphs showing improved performance in a controlled study.

Having taught in both modes, can you see on-the-ground evidence that by using POGIL students are learning more than they would in a traditional method of instruction?

Glen: The short answer is that it’s too early to draw any conclusions. I started to using POGIL in a 300-level class this last spring semester. We did four different POGILs, at different times throughout the semester. That’s about once or twice a month. (Click here to view a sample POGIL.) I don’t yet have solid evidence that there is a correlation between student performance or enjoyment of the course, and whether or not it’s attributed to POGIL. It’s still early going, and I’ll have a better sense as add more POGIL activities when I teach the same course several times. So far students have not reported any negative comments about POGIL activities. I did see on my latest course response forms where students wrote “the POGILs were helpful.” So that was good to see.

How might one get started with POGIL?

Glen: The nice thing about the POGIL community as a whole is that there is a systematic way to distribute activities that have been field tested, peer-reviewed and evaluated. So while these questions and worksheets take about the same time that you would take to prepare a straight lecture. There are already created and tested activities you can work from. For example, with the Animal Physiology class, I adapted activities from a Human Physiology POGIL text. There are POGIL books for Biochemistry, Biology, and Chemistry.

Are there other benefits to POGIL?

Glen: I write lots of letters of recommendation, especially for Pre-Med students. When you look up what medical schools, and many employers are looking for, they’re looking for process skills. Sure, they want knowledgeable students. But they also want to know that students can work together in team and know how to manage time. And these are process skills that can I can watch get developed during class time.

So assessment-wise, I’m hearing you say as a scientist that it is too early to say yet, but it’s looking good so far. I would argue you’re voting with your feet, right?

Glen: I think it’s the right way to go. I find the evidence from larger scale supporting activities like POGIL compelling. I think it is a way to make learning fun and engaging. I also think this style of teaching promotes and develops the kinds of qualities we want from critically thinking scholars.

In what way does the process goals side of POGIL connect to your department?

Glen: In the Biology Department, we’re trying really hard to level the playing field for underrepresented minorities wanting to learn STEM, (science, technology, engineering, and math). POGIL is an excellent mechanism for facilitating and enhancing learning experiences, especially in the first and second year. In fact, they’re using this even in medical schools now. They’re incorporating POGIL-type activities from large imposing lecture halls to smaller communities of students. This style of teaching can help students who are interested in sciences with different levels of preparation continue to develop a lifelong interest in learning science. And that’s something that we really want to happen.

Resources:

Process-oriented guided-inquiry learning in an introductory anatomy and physiology course with a diverse student population, by Patrick J. P. Brown

Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics, by Scott Freeman, Sarah Eddy, Miles McDonough, Michelle Smith, Nnadozie Okoroafor, Hannah Jordt, and Mary Pat Wenderoth

Learning Goals:

Engage in independent research, inquiry, and/or creative expression.

Read, listen, and observe discerningly

Think critically, creatively, and independently