It’s official: the Daley show is ending at the West Wing.

In a move that reportedly surprised President Obama, chief of staff Bill Daley told the President last Tuesday that he would be stepping down, effective at the end of the month. His resignation was only announced today (and no, it’s not a coincidence that the announcement was slipped in during the day before the New Hampshire primary) after Obama reportedly failed to talk Daley out of his decision. (Do I believe this? I do not.) Daley will be replaced by current OMB director Jake Lew.

Daley had been slated to leave his position after the 2012 election, and no reason was given, other than Daley’s desire to spend more time with his family, for the accelerated departure. However, as I’ve discussed in previous posts, Daley’s tight management style had rubbed some of Obama’s junior White House aides the wrong way, and he was not very popular with the Democratic leadership on Capitol Hill either. Some press reports also indicated he clashed with members of Obama’s campaign team. More generally, as I argued here, highly visible chief of staffs who combined the traditional administrative coordinator’s role with control over the policy development and political outreach functions tend to have rather short tenures in the White House. All told Daley will have served about a year as Obama’s chief of staff – far shorter than predecessors’ average of roughly 2 ½ year in this high profile job. Here’s the list of the previous Chief of Staff’s dating back to Eisenhower’s administration.

| Chief | Years | President |

| Sherman Adams | 1953-1958 | Eisenhower |

| Wilton Persons | 1958-1961 | Eisenhower |

| H. R. Haldeman | 1969-1973 | Nixon |

| Alexander Haig | 1973-1974 | Nixon |

| Donald Rumsfeld | 1974-1975 | Ford |

| Dick Cheney | 1975-1977 | Ford |

| Hamilton Jordan | 1979-1980 | Carter |

| Jack Watson | 1980-1981 | Carter |

| James Baker | 1981-1985 | Reagan |

| Donald Regan | 1985-1987 | Reagan |

| Howard Baker | 1987-1988 | Reagan |

| Kenneth Duberstein | 1988-1989 | Reagan |

| John H. Sununu | 1989-1991 | Bush I |

| Samuel K. Skinner | 1991-1992 | Bush I |

| James Baker | 1992-1993 | Bush I |

| Mack McLarty | 1993-1994 | Clinton |

| Leon Panetta | 1994-1997 | Clinton |

| Erskine Bowles | 1997-1998 | Clinton |

| John Podesta | 1998-2001 | Clinton |

| Andrew Card | 2001-2006 | Bush II |

| Joshua Bolten | 2006-2009 | Bush II |

| Rahm Emanuel | 2009-2010 | Obama |

| Pete Rouse (Interim) | 2010-2011 | Obama |

| William M. Daley | 2011-2012 | Obama |

| Jacob Lew | 2012-present | Obama |

As you can see, no president has gone through as many chiefs of staff in their first term as Obama has to date.

The more immediate cause for Daley’s resignation, however, may have been the decision, reported in early November, to strip Daley of some of his internal management duties. White House veterans know that the source of the chief of staff’s power is his control over the key daily administrative processes: the paper flow, scheduling, and personnel decisions. Those duties had been delegated to Pete Rouse, who had served as interim chief of staff in the period between Rahm Emanuel’s departure and Daley’s appointment last January. Without control of those processes, and lacking strong connections to Congress, Daley’s influence was likely already on the wane. Although no statement was made regarding whether Lew will regain control of these administrative processes, he does have stronger ties to Capitol Hill due in part to his experience as a senior policy adviser to former House Speaker Tip O’Neill. Lew also served in the State Department during Clinton’s presidency.

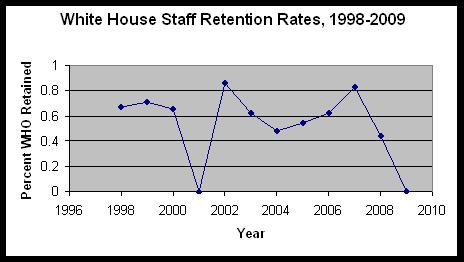

Coming on the heels of NY Times reporter Jodi Kantor’s book The Obamas that purportedly documents discord within the Obama White House, (see also here), Daley’s resignation will undoubtedly add more fuel to the speculative fire. In fact, however, Daley’s resignation fits in with a long-term historical trend that sees much higher White House staff turnover rates in the post-1968 modern presidential selection process than in previous decades. The basic reason for the increase in turnover, as I’ve argued before, is that the skills needed to govern are not always the same ones that are required for campaigning in the modern era. As presidents gear up for reelection, then, there tends to be significant staff turnover as aides are either replaced or moved out to join the campaign staff. So far, the turnover in the Obama administration has closely followed this historical pattern. Indeed, Daley is slated to become one of the co-chairs of Obama’s reelection campaign, although it is unclear just how much influence he will have in this position.

Media pundits tend to see every change in White House personnel as a reflection of personality differences, policy disagreements and clashing egos. In fact, the causes usually are rooted in more fundamental rhythms that affect all modern White House staffs. Among these, perhaps none is more important than the organizational transition from governing to campaigning – exactly the transition the Obama White House has been undergoing in recent months. Rather than discord, then, Daley’s resignation seems entirely consistent with previous historical patterns.

It remains to be seen, however, if Obama will be singing a different tune after the November elections:

You remember that rainy evenin’

I threw you out….with nothin’ but a fine tooth comb

Ya, I know I’m to blame, now… ain’t it a shame

Bill Daley, won’t you please come home

[youtube /v/BfmAs85IFVA?version=3&feature=player_detailpage”><param name=”allowFullScreen” value=”true”><param name=”allowScriptAccess” value=”always”>]