This week’s Sunday Shorts:

President Obama’s decision to engage in an open-ended air campaign designed to prevent the militant group Islamic State (IS) from expanding its territorial hold in Iraq has, predictably, been lambasted by critics on the Left and the Right. Progressives see it as a potential first step down the slippery slope of greater military involvement and a violation of Obama’s campaign pledge for a full disengagement of U.S. military forces from Iraq. Conservatives argue that it is too little, too late because it does nothing to prevent the Sunni extremist group from solidifying its territorial hold and using it as a base to destabilize the Mideast and, eventually, launch terrorist attacks against the United States. Lost in the storm of partisan handwringing, however, is any mention that Obama’s current policy roughly approximates the two “no fly zones” the U.S. and allies established after the first Gulf War ended in 1992, and which they enforced until the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003. Those two no-fly zones were designed to protect the Kurdish minority in the north and Shiite Muslims in the south from attack by Saddam’s Hussein’s forces. The difference is that the Islamic State lacks Hussein’s air capacity, but the intended effect is the same. And it was criticized as well, and for similar reasons. It is a reminder that the situational context is often more important than partisan principles when it comes to determining a president’s foreign policy choices. And it raises the distinct possibility that Obama’s current open-ended policy of targeted air strikes may be in place for a very long time.

In this earlier post, I argued that, without substantial congressional pressure, President Obama has no intention of showing his decisiveness by firing CIA director John Brennan despite Brennan’s admission that the CIA had accessed Senate Intelligence committee files. Consistent with my argument, pundits are beginning to turn their ire on Congress for failing to apply that pressure. For conservative pundits in particular, that lack of action is further reason to pursue other avenues to hold the President accountable, such as a legal suit. Whether Congress intends to apply that pressure remains to be seen. My guess is members of the Senate Intelligence committee led by Senator Dianne Feinstein may barter Brennan’s survival for White House concessions regarding redactions to the Senate report on U.S. interrogation and rendition policies.

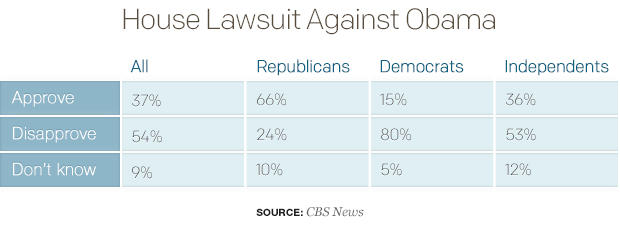

Speaking of suing the president, in this previous post I made the argument that the House Republicans’ vote to authorize Speaker Obama to do just that made perfect political sense, even though it was unlikely to gain any traction in the courts. Here’s the reason why:

As you can see by the breakdown in partisan support, Republicans who run on this issue in the upcoming midterms are banking on turnout from their base, while at the same time expecting a lower turnout from the Obama coalition which draws much more heavily on voters less likely to participate in a midterm elections. So they see suing as a winning political issue.

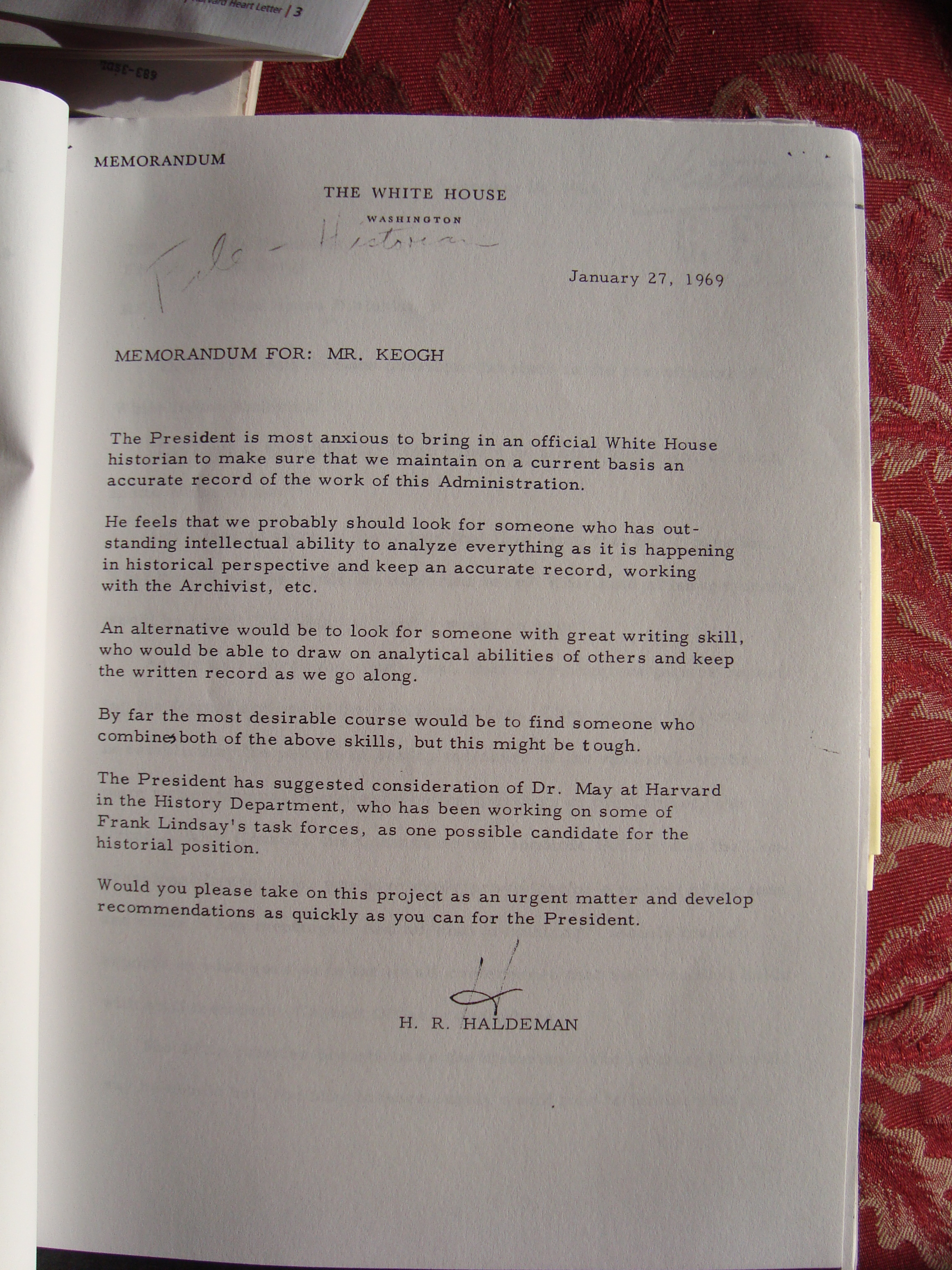

Meanwhile, Timothy Noah has written an almost entirely speculative piece on whether Richard Nixon ordered the Watergate break-in, complete with misleading headline. Noah concludes that he did. To my knowledge, there is no evidence to support Noah’s assertion, with the exception of a claim by Nixon aide Jeb Magruder many years after the fact that he overheard Nixon authorize the bugging of Larry O’Brien’s phone in the Democratic party headquarters. However, this contradicts Magruder’s earlier claims and is not supported by any evidence from tapes or phone records. Indeed, Noah’s assertion seems undermined by the recordings of Nixon discussing the break-in, which on the whole indicate complete puzzlement on his part regarding why anyone would do something so stupid.

So, if there’s no evidence Nixon orchestrated the Watergate break in, this leads to the obvious question: who ordered Noah to write this opinion piece? I am skeptical that he would do something like this on his own. Was it Rachel Maddow? The head of MSNBC? Democratic political operatives trying to use Nixon against the Republicans this fall? Noah is clearly just the fall guy – some enterprising journalist needs to follow the viewers’ clicks trail to see who really benefits here.

Finally, what does it feel like to be President? I imagine it’s often something like this:

Have a great Sunday!

UPDATE 9.45 Monday: A couple years back Jonathan Bernstein took on the “Did Nixon order the Watergate break in?” question and had pretty much the same reaction then as I did yesterday to Noah’s post: http://plainblogaboutpolitics.blogspot.com/2012/06/why-dnc.html