Here are Sunday’s Shorts:

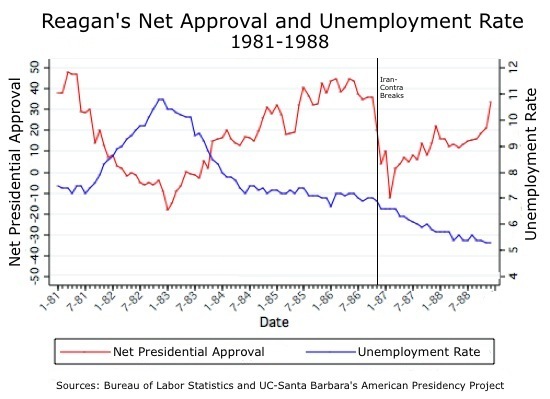

On this day in 1985, a 74-year old Ronald Reagan underwent surgery to remove a benign polyp from his intestine. While under the knife doctors discovered a cancerous polyp which necessitated a second surgery to remove a portion of his intestine. The event would be of little historical interest (Reagan made a full recovery) were it not for the fact that this also marks the period during which Reagan first approved what became the Iran-contra affair – the ill-fated effort to trade American arms to Iran in return for their help in securing the release of Americans held hostage by Mideast terrorist groups. In his July 17th diary entry, Reagan writes, “Some strange soundings are coming from some Iranians. Bud M. [Robert McFarlane, Reagan’s National Security adviser who initiated the plan to trade arms for hostages] will be here to talk about it. It could be a breakthrough on getting our seven kidnaps victims back. Evidently the Iranian economy is disintegrating fast under the strain of war” [excerpt reprinted in Lou Cannon’s Role of a Lifetime]. McFarlane met with Reagan in the hospital the next day, with only Chief of Staff Don Regan present, and informed the President that it might be possible to open up a communication channel, using Israeli officials as intermediaries, with members of the Iranian government. McFarlane’s goal in initiating contact was largely strategic; he sought to better position the U.S. to address the power vacuum likely to occur in the aftermath of the death of the Iranian leader Ayatollah Khomeini. However, it is clear that Reagan’s primary motive in agreeing to McFarlane’s plan was to secure the release of the hostages, which included the Mideast CIA station chief William Buckley. Reagan had just come off a meeting with one of the hostage’s families and was visibly moved by their appeals to him to do something. However, there is no evidence that either McFarlane or Regan made it clear to Reagan that by subsequently approving the sale of arms to Iran in order to secure the hostages’ release, Reagan was in effect negotiating with kidnappers, thus violating administration policy. Indeed, there is some question whether Reagan, who was recovering from major surgery, was in the best frame of mind to consider such a momentous decision. When pressed later by members of the Tower Commission to recall when he actually approved sending arms to the Iranians, Reagan gave conflicting accounts and it became clear that he simply didn’t remember when, or even if, he gave the initial approval. It is a reminder that although we quite rightly hold presidents solely accountable for the decisions they make, those decision are based in part on the information, expertise and advice of their advisers. In this case Reagan’s advisers failed the President, with significant consequences.

Here’s Reagan’s national address almost two years later, on March 4, 1987, in the aftermath of the report of the Tower Commission which he appointed to investigate the Iran-contra affair, in which Reagan finally admits he traded arms for hostages:

[youtube.com/watch?v=R67CH-qhXJs]Meanwhile, in the aftermath of the announcement that the Republicans will hold their 2016 nominating convention in Cleveland, Harry Enten presents the following data regarding the impact of convention siting on election results. If conventions boost a candidate’s performance in that state, one would “expect to see a party’s candidate improve relative to his national performance as compared with the same party’s candidate four years ago. For example, the GOP convention in 2012 was held in Tampa, so Mitt Romney should have done better in Florida than John McCain did in 2008, once we control for the fact that he did better nationwide.” But that’s not what Enten finds. Consistent with my post on the matter, Harry concludes: “There is no proof that a convention site has much effect on a state’s voting patterns.”

Hope you had a great Sunday!