In the last several posts I have been presenting evidence indicating that rather than the “post-partisan” presidency promised during his campaign, Obama has in fact proved every bit as polarizing as his immediate predecessors. With hindsight, some of you are now arguing that there was no reason to expect Obama to be anything but a partisan president, but a careful read of his campaign speeches clearly indicates that he held out hope for a change in the tone of Washington politics, in addition to a change in policy direction. And, contrary to what many of you are now saying, at the time of his election not a few of you believed he would in fact bring not just a new policy direction, but also a new more civilized mode of political discourse on Capitol Hill. Indeed, if I heard a variation of the following refrain from colleagues and students once, I heard it 100 times: “I’m really optimistic that Obama’s election will finally end the partisan bickering in Washington.” Admit it – you were one of those who believed, weren’t you? (You know who you are!)

Of course, this was never likely to happen, as I quietly tried to suggest in my earlier blog postings and talks during the transition and aftermath of the inauguration. My goal in harping on this theme is not to cast myself as a latter-day Cassandra. Instead, it is to make three broader teaching points. (After all, that’s the point of this blog!) First, there was an inherent tension in Obama’s promise to bring policy change AND to lower the degree of partisan bickering on Capitol Hill. He was unlikely to accomplish both objectives and, in the end, not surprisingly chose partisanship and policy change over bipartisanship. To do otherwise – to pursue a more bipartisan strategy – would have required an enormous expenditure of political capital. Second, the polarized politics that have characterized presidential-congressional relations are not due primarily to the actions of any single president, but instead are largely the result of the confluence of several long-term trends in American politics. By understanding why polarization exists, we are less likely to be disappointed by Obama’s failure to change that tone – it really has little to do with his skills or style of leadership. Similarly, once we understand the sources of polarization, we are better able to adopt a more realistic assessment of previous presidents’ culpability for the current state of affairs. Third – and this is one of the main reasons why I write this blog – Obama’s failure to usher in the era of the post-partisan presidency reminds us that presidents possess much less influence than pundits and journalists would have us believe. Ours is not a presidential form of government so much as it is a congressionally-centered system.

Some of you are now arguing that partisanship may be a good thing, or at least less worrisome, as long as policy change occurs. I will devote a separate post examining this question, in part by looking at the production of legislation under various partisan permutations. But note that partisanship is not without its costs. Eventually, a polarized debate on Capitol Hill will filter down to the public, and we will see Obama’s popularity approval ratings exhibit the same polarized division that characterized Bush’s support. Indeed, this is already happening; in the aftermath of congressional passage of the economic stimulus bill followed by the first budget resolution – both of which took place with almost no Republican support – we already see Obama’s popularity exhibiting Bush-like characteristics. According to Amy Walter at the National Journal the latest Diageo/Hotline poll shows that just 19 percent of Republicans thought more government involvement in the economy is a good idea, compared with 79 percent of Democrats. “Asked if they think the stimulus plan will be successful in turning the economy around, 72 percent of Republicans said no while 86 percent of Democrats said yes” (see article here).

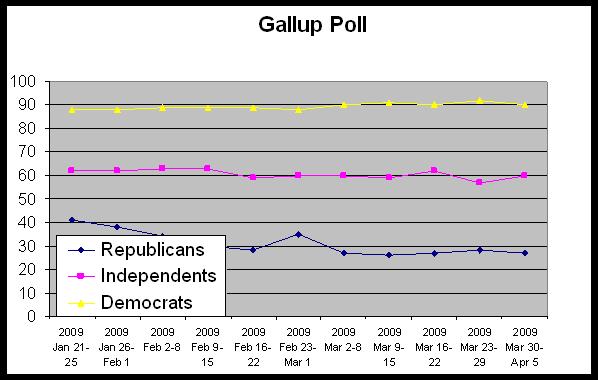

Of course, it may not be surprising that Republicans – only 9% of whom supported Obama in the election – are registering disapproval of Obama in increasing numbers, based in large part on his economic policies, while Democratic support remains high. But what of the key swing group, the independents? By the end of Bush’s presidency, only about 30% of independents approved of his job as president. Obama won the independent vote in November by 52-44, and so far, his support among this group remains strong. According to the March 30-April 5 Gallup Poll (see table below), his approval among independents is 60% – almost exactly what it was on inauguration day and pretty much where it has remained ever since.

However, Walter, citing the Diego poll, notes that those independents who said they “strongly” approve of the job Obama is doing dropped 13 points between the end of January and the end of March. She also notes that that independents’ support for Congressional Democrats is softening as well: “From the beginning of March to the end of the month, the approval ratings of congressional Democrats among independent voters dropped 10 points, from 48 percent to 38 percent. Same goes for the generic ballot test. In our most recent poll, independents gave a slight edge to Republicans (26 percent to 23 percent) — a 6-point drop for Democrats since early March.”

As yet, the drop in independents’ support for Democrats has not translated into an increase in their support for Republicans now in Congress. Walters notes that, “Just 26 percent of independents approve of the job Republicans are doing in Congress (a 4-point drop since early March). The 26 percent that Republicans are getting in the generic matchup is unchanged since early March as well.” We see, then, that among independents, support for Obama is strong, but potentially softening. However, most of the erosion in independent support seems focused on the Democrats in Congress. Whether and to what degree that will extend to a loss of support for Obama depends, I believe, in large part on perceptions regarding the economy. Polarization within the public becomes a major problem, I argue, when it includes a loss of support among independents, and not just Republicans.

So, why does polarization exist? One reason is the efforts by well-meaning reformers to reduce the influence of money on elections. Many of you will recall that in his 2004 run for the Democratic nomination for president, Howard Dean trumpeted the fact that a huge proportion of his campaign contributions came in small amounts, often under $200. In 2008, Barack Obama picked up on this theme, arguing that he was broadening popular participation in elections by attracting financial support from those who represented the “average”, less wealthy voter, rather than the “fat cats” who typically funded campaigns. In their view, the internet was “democratizing” presidential campaigns. As my colleague Bert Johnson’s research reveals, however, this is not what was happening – at least not in the way that the Dean-Obama campaigns would have us believe. Their fundraising strategy did not mobilize the less partisan, middle-of-the-road voter. In fact, it benefitted from – and may actually have contributed to – the increased partisan polarization that characterizes American politics today. To understand why, and to appreciate some really innovative research, I want to devote the next post to Bert’s research on campaign finance. He tells a fascinating – and counterintuitive – story that merits a full discussion, and helps illustrate two of Dickinson’s three laws of politics: “Money always finds its way to candidates” and “For every positive benefit from a political reform, there is an equal and unanticipated negative reaction.”