Howard Baker, the three-term Republican Senator from Tennessee, died last week at age 88. He was remembered, and deservedly so, as “the great conciliator” who in his eight years as the Republican Senate leader (including four as majority leader) forged a reputation as a moderate (despite a rather conservative voting record) who was able to work both sides of the political aisle. But perhaps his most important service to the nation took place after he left the Senate. In early 1987, the Reagan administration was in full damage control as it struggled to deal with political fallout from the Iran-contra affair. As most of you know, despite a public policy of never negotiating with terrorists, Reagan had in fact secretly authorized the trading of arms to Iranian “moderates” in return for their help in negotiating the release of Americans held hostage by various Mideast terrorist factions. Moreover, overpayments from those sales had, evidently without Reagan’s knowledge, been used to support the Nicaraguan contras in their struggle against the Soviet-backed Sandinista government despite a congressional ban on U.S. aid to these “freedom fighters”.

Somewhat belatedly, and only after prodding from his wife Nancy, Reagan agreed to replace his chief of staff Don Regan, under whose watch the Iran-contra affair occurred, with Baker who, at the time, was widely perceived to be a front-runner for the 1988 Republican presidential nomination. It took a personal plea from Reagan to convince the reluctant Baker to take the job in the national interest. But as Jane Mayer and Doyle McManus recount in their excellent book Landslide, Baker did so while keenly aware of a whispering campaign that Reagan had begun to show signs of mental deterioration. It was only after directly observing Reagan handling a variety of presidential responsibilities that Baker concluded the rumors were untrue. He went on to orchestrate the resurrection of Reagan’s presidency, even at the expense of his own presidential aspirations. In Reagan biographer Lou Cannon’s words, “More than any single person, it was Howard Baker who brought Reagan back.” That may have been his greatest service to the country.

Jill Abramson, the deposed New York Times executive editor, has landed on her feet with a lecturer position in the English department at Harvard University. I had hoped to do a separate post on the circumstance surrounding her firing, but more important events took precedent. As you will recall, Abramson was let go amid conflicting reports regarding whether, and to what degree, gender played a role in her firings. In the media hullabaloo that followed, I thought one important point was underplayed: whether or not gender mattered in Abramson’s firing, the fact that it became an issue in the ensuing discussion suggests we have a way to go before there is true work-place parity. The reality is that women are fired from high-profile management positions all the time. Until those decisions are discussed solely on the basis of the woman’s own (in)competence, it’s hard to argue that we have true gender equality.

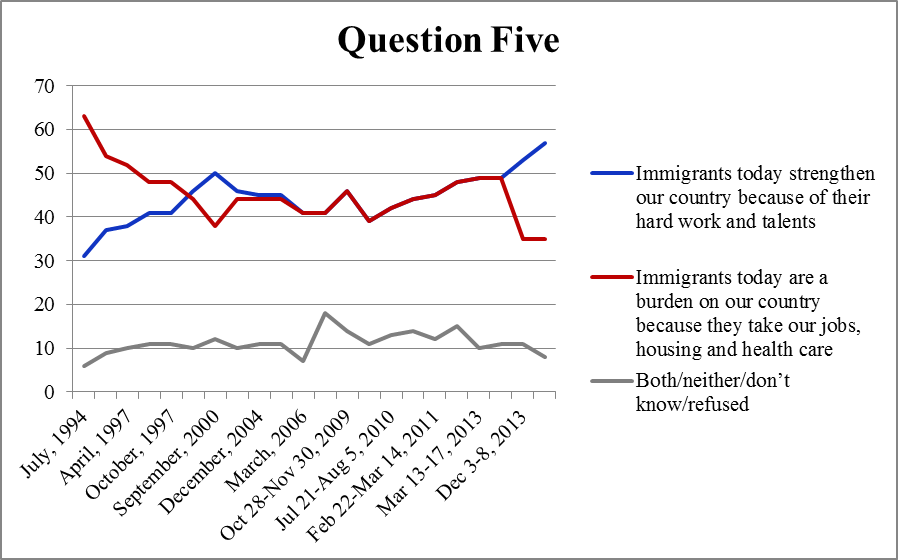

Finally, Stanford political scientist Morris Fiorina tries once again to set the record straight regarding what the Pew Report report really says regarding whether Americans are becoming increasingly polarized. This relatively short interview (listen here) is worth a listen – pay particular attention to what happens when you ask a moderate public to choose between two relatively polarized options. Note also that increasing ideological consistency is not evidence of increasing polarization. The bottom line? There is no evidence of increasing ideological polarization in the public at large in the last three decades – contrary to what many pundits have said based on the Pew survey.

Have a great Sunday!