There’s no doubt that, as midterms go, President Obama has not fared well. In 2010, his Democratic Party lost 63 House seats – the biggest midterm loss in that chamber since 1938 – and with it control of the House to the Republicans. Although they also lost six Senate seats, Democrats were at least able to retain their majority there. Four years later, however, Democrats lost the Senate too when Republicans picked up 8 Senate seats in the 2014 midterms – with one more still at stake – to regain a Senate majority. Republicans also padded their House majority by gaining a dozen more seats (a handful of House races have yet to be decided). The net result is that Obama is facing an opposition-controlled Congress for the last two years of his presidency.

The successive Republican waves are particularly devastating because they swept away what many pundits believed to be a coming period of Democratic electoral dominance. When Obama was elected President in 2008, he appeared to display substantial coattails; Democrats picked up 25 House and 8 Senate seats and enjoyed comfortable majorities in both chambers. More importantly, demographic trends suggested the size of the Democratic voting coalition was likely to expand in the coming years. In short, Obama’s election was, as one pundit put it at the time, “likely to create a new governing majority coalition that could dominate American politics for a generation or more.” Instead, the purported realignment lasted a bit less than two years. To borrow one of the catch phrases of Red Sox radio announcer Joe Castiglione, the Obama presidency has been, politically at least, “a giant squander”.

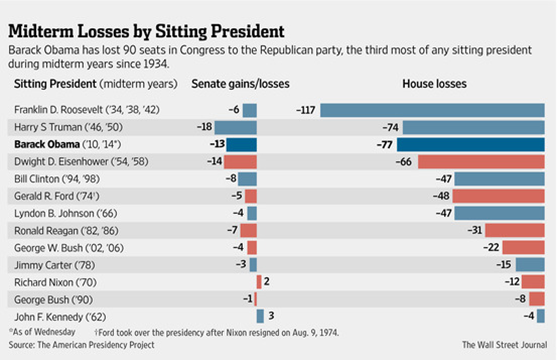

But just how big a squander is it, historically speaking? One chart that made the rounds of the twitterverse this week indicates it was a very big squander indeed. It shows that Obama’s Democrats have suffered a net loss of 13 Senate and 77 House seats during the two midterms held in his presidency, which ranks as the third worst cumulative midterm seat loss among modern presidents, behind only FDR and Truman.

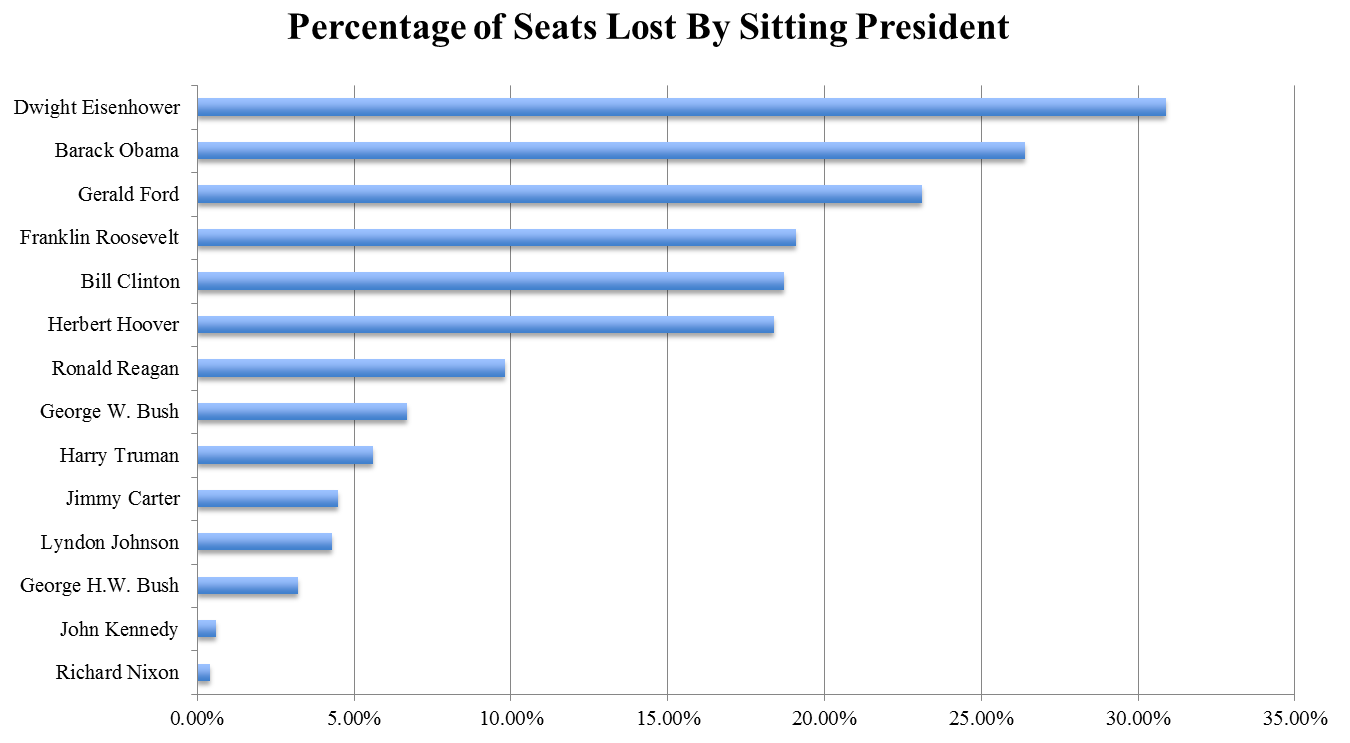

But is this really a useful metric? Roosevelt, who suffered the greatest cumulative seat loss, is nonetheless typically ranked as one of the nation’s three best presidents – someone who was the consummate political leader. The problem with using total seat loss as a measuring rod is that presidents like FDR who enter office with substantial coattails, as indicated by large partisan majorities, and who serve the longest – both arguably measures of political skill – stand a greater probability of losing more seats. Moreover, looking only at midterms may not be a fair measure of a president’s party leadership since midterms operate under such unfavorable dynamics to the president. Perhaps a better metric is to assess the proportion of seats a president loses over the course of his presidency in all elections. This is not perfect, of course, because it still penalizes presidents who enter with a substantial governing majority – they have greater room to fall – but it is probably a better gauge of a president’s political pull than a raw seat count of midterms alone. Middlebury College student Tina Berger calculated that figure for all the modern presidents and summarized the totals in this chart.

Alas, Obama does even worse by this standard – among modern presidents only Dwight Eisenhower lost a greater proportion of party seats across his presidency. The Republican Ike, however, presided in the midst of the post-Depression Democratic-dominated era (he was the only Republican president to serve between 1933 and 1969) and he managed to retain his personal popularity even as control of Congress reverted to what might be called its natural partisan state during this New Deal period. Obama, in contrast, has watched his popularity stagnate in the low 40% approval level for the better part of a year and with Democrats winning four of the last six presidential elections, it can hardly be called a Republican era (Karl Rove’s McKinleyesque visions notwithstanding.)

Alas, Obama does even worse by this standard – among modern presidents only Dwight Eisenhower lost a greater proportion of party seats across his presidency. The Republican Ike, however, presided in the midst of the post-Depression Democratic-dominated era (he was the only Republican president to serve between 1933 and 1969) and he managed to retain his personal popularity even as control of Congress reverted to what might be called its natural partisan state during this New Deal period. Obama, in contrast, has watched his popularity stagnate in the low 40% approval level for the better part of a year and with Democrats winning four of the last six presidential elections, it can hardly be called a Republican era (Karl Rove’s McKinleyesque visions notwithstanding.)

To be sure, not all of the blame for Democrats’ losses can be pinned on Obama. Surely the Party’s congressional wing is partly culpable for its dismal showing. Nor should we forget when judging his political leadership that Obama won reelection in 2012, and did so while helping Democrats net eight House and two Senate seats. The bottom line, however, is that in this era of nationalized politics, elections – even mid-year ones – are invariably in large part referendums on the president’s performance. And, at least by this one metric, Obama appears to have come up short.

Where did it all go wrong? Pundits are quick to blame the President’s detached leadership style but as I’ve noted in previous posts, it’s not clear how much temperament or character really matters. The fact is that Obama inherited an economic mess and a war on terror – two issues that defy easy solutions under the best of political circumstances. Moreover, as David Mayhew persuasively argues, the American system of separated institutions, each operating according to its own electoral clock and responding to different constituencies, seems to possess a systemic equilibrating tendency that prevents either party from holding onto strong majorities for very long, regardless of the president’s skills. In this respect Obama’s presidency demonstrated a not unexpected reversion to the political mean.

Still, I doubt very many pundits in 2008 predicted the speed and degree to which Obama’s governing majorities would dissipate – if they predicted dissipation at all. If one were to isolate one primary reason for this speedy partisan erosion, it is probably Obama’s decision to pursue health care reform despite strong Republican opposition and lukewarm public support. Along with the economic stimulus bill, health care proved to be the focal point of Republican resistance early in his presidency, and his failure to bring even a single Republican aboard when passing Obamacare cemented the partisan divisions that have come to characterize our national politics, and provided a rallying point for Republicans as they fought to regain partisan control of Congress. This is not to say pursuing health care reform was a mistake. It is to say that Obama – and his Democratic Party – paid a steep political price for doing so.

And so I wonder: as he contemplates finishing out his presidency facing two years of an opposition-controlled Congress, and with the fate of his signature piece of legislation now partly in the hands of the Supreme Court, does the President ever ask himself whether passing health care reform was really worth it?