This week we take the WayBack machine to revisit an exchange in the White House Oval Office between President Harry Truman and some public administration scholars that provides a fascinating window into Truman’s perspective on being president – and what President Obama can learn from Truman’s views. According to the transcript of the meeting, Truman is asked at one point whether he agrees with President Taft’s characterization of the Presidency as “the loneliest job in the world”. Truman replied, “Oh yes, it’s true.” Here is part of his full response to that question:

The irony of Truman’s observation, of course, is that he was anything but alone in this, the loneliest job in the world. As Truman explained earlier in the conversation, “I have a number of Secretaries and assistants here, who are of immense help to me.” One of those was his Appointment Secretary, Matt Connelly, “whose business it is to see that the people get in that should get in. You see, I can’t see everybody that wants to see me….It took me a long time to figure that out.” Truman noted that as a Senator, he had been used to seeing “two or three hundred [people] a day…and saw each one individually. … But the President can’t do that. His callers have to be screened and confined to those who really have business that the President needs to talk about, or needs to transact.”

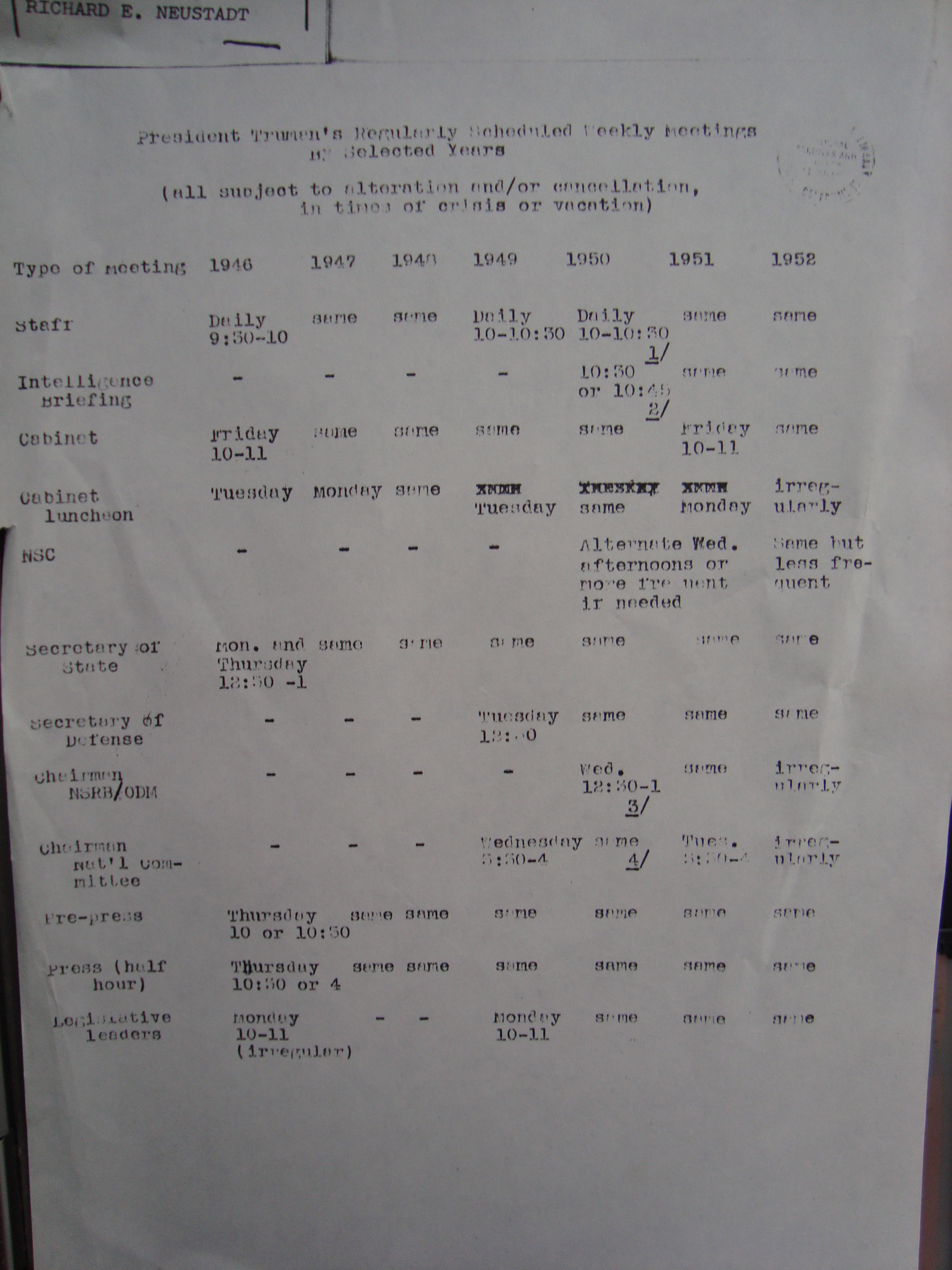

Who were those people that Truman deemed “really” necessary to see? Truman’s review of his daily schedule above shows that he was a very busy man, but it does not indicate with whom he met with regularly. However, notes from a study by his White House assistant Richard Neustadt gives us a glimpse into Truman’s regular appointments throughout his presidency. Here is an overview of Neustadt’s findings:

In looking at Truman’s regular schedule of meetings, there are several items of particular interest. First, he operated without a chief of staff, choosing instead to manage his staff on his own. This meant scheduling a daily staff meeting with his senior White House aides, during which he would hand out assignments and receive oral reports. By all accounts this was a tremendously helpful administrative exercise, not least because it kept each senior aide apprised of what his colleagues were doing. Presidents have long since given up this practice, choosing instead to delegate staff oversight to a single senior aide.

Second, Truman does not begin daily intelligence briefings until 1950 which, not coincidentally, marks the start of the Korean War that June. Interestingly, however, those briefings were conducted initially by General Omar Bradly, who was serving as the first chairman of the newly created Joint Chiefs of Staff, and not by the CIA director or a personal White House equivalent to the national security adviser.

Third, Truman met weekly with both his full cabinet and with the press. Neither practice continues today. Most of Truman’s successors, beginning with JFK, complained that the cabinet had become simply too large and unwieldy to justify regular cabinet meetings. Instead presidents have opted to meet with smaller, issue-based cabinet councils, usually under the direction of a White House aide. At the same time, for reasons I discuss here, presidents find regular press conferences far less useful than in Truman’s day.

But perhaps of greatest relevance to today are Truman’s regular Monday meetings with the congressional “Big Four” – the House Speaker and majority leader, and the Senate majority leader and president pro tempore. In addition to these weekly get togethers with the congressional party leadership, however, Truman’s schedule is studded with additional meetings with senators and representatives of both parties. Neustadt’s notations indicate that many of these meetings dealt with regional issues of concern to the particular member of Congress, while others dealt with national policy. For example, in June 1947 Truman met with Senator John Overton to discuss flood control in Louisiana, with Alabama Senator John Sparkman “re War Dept. run out on cotton”, and with House Labor Committee Republicans to discuss their opposition to the Taft-Hartley act – just three of 13 separate meetings with senators and seven more with representatives Neustadt records for that month.

It is perhaps not surprising that Truman, the former Senator, took such pains to keep in regular personal contact with those at the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue. In the notes Neustadt kept of his 1958 interview with the ex-president for his book Presidential Power, Truman discusses his views toward Congress in the context of his disapproval of White House aides “swarming over the Hill” on the president’s behalf: “I didn’t believe in it; never did….[M]y attitude formed in my early years in the Senate. I always believed Congress was a co-equal branch, just like the Court; the President should tell them what he thinks right and then it’s up to them…There’s bound to be some inefficiency [but] it’s worth it. [A] Congressman’s entitled to talk to the President directly and be talked to directly, not second hand….they resent it.”

I thought about Truman’s remarks after having dinner recently with a former member of the House who remains in somewhat close contact with current members of Congress. According to him, legislators on Capitol Hill from both parties do not believe President Obama is sensitive enough to the need for reaching out to the Hill on a regular basis. Of course, this is a complaint one hears voiced on a frequent basis in media reports, but it is difficult in the absence of records like Neustadt’s to verify just how often the President meets with his legislative counterparts. If true, however, it may explain in part why a President – and former Senator – ostensibly committed to changing the culture of Washington has apparently made so little headway toward reaching this objective.

The Presidency is already the loneliest job in the world. Truman’s words, and actions, are a reminder that it makes no sense to further the isolation by failing to reach out regularly to those with whom you share power.