I don’t normally focus too much attention on one survey, but when it helps illuminate a broader (and not uncontroversial) argument I’ve made it becomes too good to pass up.

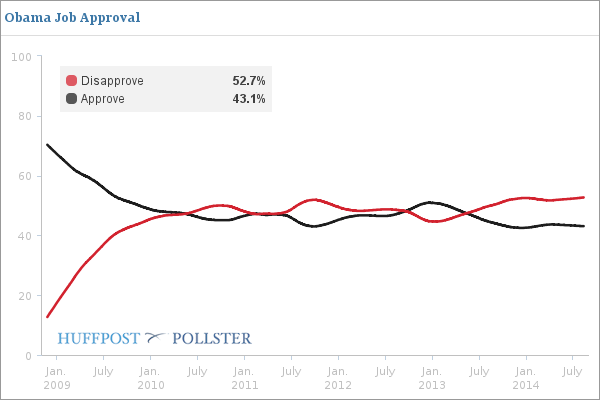

Readers will recall that in yesterday’s post I noted that the likely explanation for President Obama’s recent sputtering approval ratings in the face of an incrementally improving economy is a spate of bad news from overseas. The results of this McClatchy-Marist poll, in the field August 4-7, are consistent with my analysis. It shows Obama’s approval rating languishing at 40%, the second lowest of his presidency, and the lowest it has fallen in three years. (He was at 39% approval in a September 2011 McClatchy poll.)

More importantly, in the poll Obama gets dismal ratings for his handling of foreign policy, with only 33% approving of his performance in this area, compared to 61% who disapprove. That’s a decline of 13% in approval since the start of this year, and a decline of 9% since April. As I suggested yesterday, that nosedive appears to be driven most recently by the public’s perception of events in the Mideast and in the Ukraine, as well as Iraq. Only 30% of respondents approve the President’s handling of the Israeli-Hamas conflict, and only 32% give Obama favorable marks for his dealing with Russia regarding the Ukraine struggle. (McClatchy didn’t ask about the Islamic State insurgency in Iraq, but I am confident that is also contributing to Obama’s loss of support.) In comparison, while his handling of the economy gets relatively low marks, at 39% approving, that level has remained relatively consistent for over a year now. So it appears that foreign policy is keeping Obama’s polling numbers low for now.

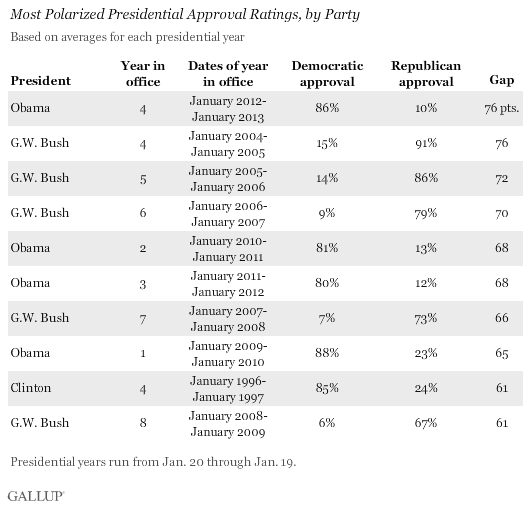

As you might expect in an era of deep party sorting, there is a pronounced partisan divide in Obama’s approval numbers with Democrats showing far greater support for his handling of issues, including foreign policy, than do Republicans. However, what is most telling is his declining support among independents who, as I noted in my previous post, are a growing portion of the electorate, and who were a key component of Obama’s electoral coalition in 2008. As of today, however, Obama’s support among this voting bloc has seen a precipitous decline.

Fully 45% of respondents to the McClatchy survey now categorize themselves as independent, compared to 28% who self-identify as Democrat and 25% Republican. Among independents, 18% say they lean Republican, while 12% consider themselves “pure”, with no partisan leanings in either direction. We know from previous studies that “leaners” tend to act on those predispositions; when given a choice of two candidates, most will back the one from the party to which they lean. If this holds true to form, the survey suggests an electorate that is almost evenly divided between the two parties, with the independents likely to hold the balance of power heading into the 2012 midterms.

What is driving down Obama’s support among independents? Again, consistent with my post yesterday, Obama is not being helped by events overseas; McClatchy finds that only 31% of independents approve of Obama’s handling of foreign policy. The number is lower among independents – at 24% approval – for both his handling of the Israeli-Hamas conflict and the Ukraine conflict. More worrisome, it appears Obama’s foreign policy woes may affect the midterm results come November. When asked if “November’s election were held today, which party’s candidate are you more likely to vote for in your district?”, Republicans lead on this generic ballot question by 43-38% over Democrats. In April, by contrast, Democrats were up by 48-42%, so it has been nearly a 10% net change in support across three months. During this period the indicators measuring the health of the economy have not changed much or have indicated a slight improvement, but the salience of foreign policy has increased, and not to the President’s benefit.

It can be dangerous to put too much stock into one poll. Events overseas remain fluid, leaving the possibility that a reversal in fortune could redound to Obama’s – and Democrats’ – benefit. Moreover, we shouldn’t overstate the impact of Obama’s low approval on voters’ choices come November. Fully 51% of respondents to the McClatchy poll say their opinion of Obama won’t be a factor in their vote during the midterms, including 61% of independents who say it won’t matter. On the other hand, 41% of independents say “their impression of Obama” will make them more likely to vote Republican come November, compared to 22% who say it will make them more likely to vote Democratic. Obama’s standing within the public, particularly among independents, is one factor – but not the only one – that will affect the midterm results.

My broader point, however, is to reiterate my claim in yesterday’s post regarding why Obama’s poll numbers remain sluggish. In this era of social media and partisan-driven talking points, it is easy to blame some combination of polarization, cable news, and racial animus for his languishing approval ratings. The evidence, however, points to a more prosaic culprit: things aren’t going well overseas, and when that happens, the President, fair or not, takes the blame.