We have entered a political lull between the period in which Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton became their party’s presumptive nominees and the party conventions signifying the kickoff to the general election campaign. In a bid to drum up items of interest during this slow news period, the media will spend an inordinate amount of time speculating about who the two candidates will choose as their vice presidential running mates (along with a healthy dose of Clinton’s email woes) – an exercise that both candidates will be only to happy to encourage. These stories will contain the obligatory reference to John Nance Garner’s quip that the Vice Presidency is not “worth a bucket of warm piss”, and then will play the speculation game by pointing out the ways in which various potential candidates do or do not help the president win the general election. We’ll see references to which vice presidential candidate best “balances” the ticket – geographically, or with certain voting blocs (women, religious groups, etc.), or to compensate for a candidate’s perceived lack of expertise in certain areas.

All this begs the question: is there any evidence that the vice president pick even matters, in terms of influencing the general election? Generally speaking, the short answer is no – at least not in terms of the overall presidential vote. There is some evidence that a vice presidential candidate chosen from a swing state could be electorally consequential by boosting a presidential candidate’s support there. But the effect, if it exists, is likely quite modest. However, as I suggested to Deutsche Welle (DW) reporter Michael Knigge, as with many aspects of this election, prior research may be – I stress may be – less relevant this time around. This is particularly the case when it comes to Donald Trump’s vice presidential choice. The reason is that Trump, perhaps more than almost any major party nominee in modern history, lacks any governing experience at any political level. Beginning at least with the Carter-Mondale relationship presidents have increasingly integrated their vice president into their policy advising process. As a consequence, the vice presidential choice has been increasingly likely to turn on how well the presidential candidate believes his vice presidential nominee will help him or her govern, as opposed to boosting his electoral chances. Dick Cheney wasn’t selected by Bush because he could deliver Wyoming and its three Electoral College votes – he was chosen because he possessed the foreign policy experience George W. Bush lacked, as Bush makes clear in his memoirs. Similarly, Obama’s choice of Joe Biden was not made in order to bring Delaware into the Democratic column in 2008. Instead, Obama was hoping to capitalize on Biden’s years of experience in the Senate. And even candidates who are chosen in part for electoral reasons, as Al Gore was in 1992, often provide needed governing expertise as well. In his memoirs, Bill Clinton notes that he had weekly lunches with Gore throughout his presidency: “Al Gore helped me a lot in the early days….giving me a continuing crash course in how Washington works.”

Trump, in his public comments, seems to recognize that he needs to select someone with governing experience, preferably working in Congress. It seems, however, that as vice presidents have become an important part of the presidential staff, personal compatibility with the presidential candidate has become an increasingly important factor influencing the selection as well. In listing the qualities that ultimately led him to offer the position to Cheney, Bush said, “I wanted someone with whom I was comfortable, someone willing to serve as part of a team, someone with the Washington experience that I lacked… .”

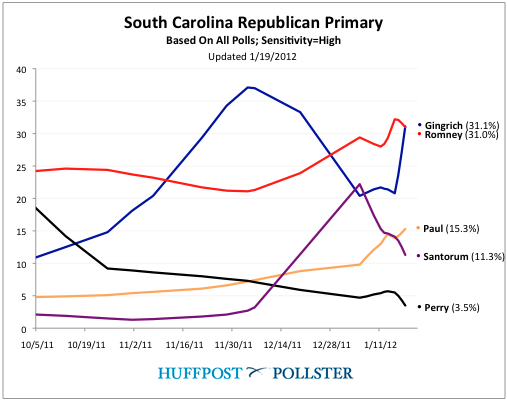

At first glance, former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, who is reportedly the front-runner to become Trump’s running mate, seems to provide the type of congressional experience that Trump will sorely need if he’s to get his legislative agenda through Congress. Even Gingrich’s harshest critics acknowledge that he is smart, and a savvy player of the Washington game. But Gingrich has also acquired a reputation for erratic behavior and a penchant for floating big think, but perhaps impractical ideas – see his proposal during the 2012 campaign for establishing a moon base by 2020. More importantly, perhaps, Gingrich seems to suffer from some of the same weaknesses Trump exhibits – a lack of self-discipline and a penchant for rhetorical excess that often attracts media attention for the wrong reasons. And his personal life – particular his marriages – isn’t likely to sit well with conservative voters who are already suspicious of Trump’s right-wing credentials and moral rectitude.

Electorally, it is not clear that Gingrich brings much to the ticket. It is true that Gingrich won his home state of Georgia easily four years earlier during the race for the Republican nomination, which might matter if Democrats try to turn that state blue – a long-shot proposition at this point. However, there are lots of more important swing states out there (see: Ohio) and politicians (see: John Kasich) who would make a better choice for electoral reasons alone. The problem, however, is that many of the Republicans who bring the most electorally, including Kasich, Tennessee Senator Bob Corker and Iowa Senator Joni Ernst, have expressed no interest in being Trump’s running mate. Gingrich, on the other hand, seems perfectly willing to climb aboard the Trump presidential train.

One important quality that Gingrich does possess, at least according to press reports, is that Trump likes and trusts him, something that is evident in Trump’s comments about Newt during their joint appearance at a rally yesterday in Cincinnati.

https://youtu.be/2T_ow1UJZJs

Who knows? A Trump-Gingrich presidential ticket might create the type of creative synergy not seen since….well, since ever. Or, the two might create a combustible mix of inflated egos and excessive rhetoric that will end up self-destructing on the campaign trail. Either way, it would be one hell of a ride.