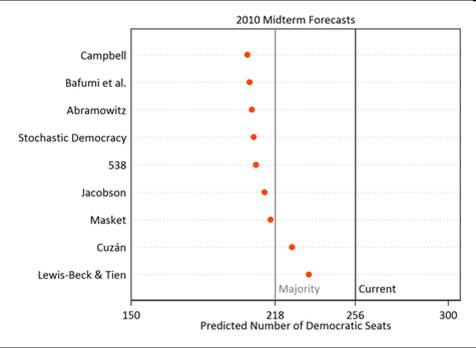

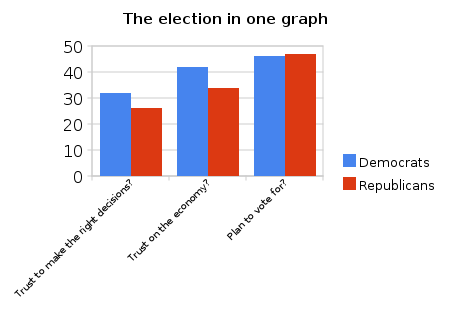

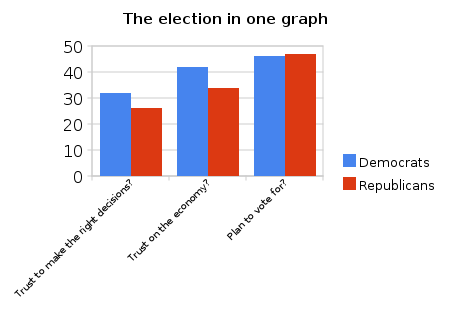

This item from yesterday’s Washington Post caught my eye as a useful teaching moment. Ezra Klein posted this graph, based on this most recent Washington Post/ABC Poll, under the label “A chart is worth a thousand words”:

It’s not clear what Klein’s point is, but presumably he means to point out just how illogical voters are, since they trust Democrats more than Republicans on handling the economy and to make the “right decisions”, and yet a plurality (by a slim percentage) are planning to vote Republicans into office.

It’s not clear what Klein’s point is, but presumably he means to point out just how illogical voters are, since they trust Democrats more than Republicans on handling the economy and to make the “right decisions”, and yet a plurality (by a slim percentage) are planning to vote Republicans into office.

There’s only one problem with this graph. If you actually go to the data in the poll from which Klein constructed it, you’ll see that the first two bars are based on a sample of all adults, while the last bar, which graphs the partisan breakdown of responses to the question “who do you plan to vote for?” is based on a sample of only registered voters.

Longtime readers have heard this refrain before, but it bears repeating for those who have just tuned in: samples based on registered voters tend to skew slightly more Republican than do samples based on all adults. The basic reason is that samples of all adults include more Democrat supporters who are less likely to vote. Or, to put it another way, Klein is comparing apples to oranges.

How big is the difference? It varies, of course, from poll to poll depending on sampling procedures, etc. Ideally, of course, we’d test the premise by having polling outfits conduct split sample surveys that compare response rates of both likely and registered voters to all adults. That’s expensive, however, so most polling outfits do one or the other. (Presumably WaPo switched to registered voters from all adults on the “who are you planning to vote for?” question because for this question they wanted to sample those most likely to vote, rather than all adults.)

However, we can get some leverage on the issue by looking at past Washington Post polls that have polled both groups in close temporal proximity, if not at the same time. Here’s an example.

18. (ASKED OF REGISTERED VOTERS) If the election for the U.S.

House of Representatives in November were being held today,

would you vote for (the Democratic candidate) or (the Republican

candidate) in your congressional district? (IF OTHER, NEITHER,

DK, REF) Would you lean toward the (Democratic candidate) or

toward the (Republican candidate)?

NET LEANED VOTE PREFERENCE

Dem Rep Other Neither Will not No

cand. cand. (vol.) (vol.) vote (vol.) opinion

7/11/10 RV 46 47 * 2 * 5

6/6/10 RV 47 44 2 2 1 4

4/25/10 RV 48 43 1 2 1 6

3/26/10 RV 48 44 1 2 * 4

2/8/10 RV 45 48 * 3 * 4

10/18/09 All 51 39 1 3 2 5

Note the big difference when WaPo switches from sampling all voters, in October, 2009 versus a sample of registered voters in February, 2010. Democrats go from being preferred by 12% to being behind by 3% – a net shift of 15%. Yes, the polls were four months apart, so it’s possible voters’ preferences simply shifted that much in the intervening time. Note that we don’t see any comparable shift in subsequent months, however.

Next, let’s look at previous WaPo/ABC polls that asked respondents which party they trusted more to handle the economy. Fortunately, in September, 2002 WaPo asked a sample of all adults “Which political party, the (Democrats) or the (Republicans), do you trust to do a better job handling the economy?” In the following month, they asked this of likely voters and then two months later of all adults again. Note that likely voters tend to skew Republican even more than registered voters. In September, the random sample of all adults indicated that they trusted the Democrats more, by 8%. The next month, when WaPo sampled only likely voters, the country changed its mind and now trusted Republicans more by 5%. That is, Republicans picked up 9% while Democrats dropped 4% in the switch from sampling all adults to sampling likely voters – a net switch of 13%. Two months later, WaPo went back to sampling all adults, and Democrats closed the trust gap, essentially matching Republicans’ support. The following table summarizes the results:

| Date |

Democrat |

Republican |

Both |

Neither |

No Opinion |

| 12/15/02 |

44 |

45 |

4 |

6 |

1 |

| 10/27/02 LV |

43 |

48 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

| 9/26/02 |

47 |

39 |

3 |

6 |

5 |

Again, it’s possible that the public’s view toward the two parties’ ability to handle the economy changed from September to October, and then shifted back from October to December. But it is more like, in my view, that the change reflects the difference response one receives when sampling all adults versus sampling likely voters.

This difference in partisan response rates for survey of all adults, registered voters, and likely voters, permeates all polls. As evidence, look at this recent Times poll asking

“There will be an election for U.S. Congress in November. If you had to decide today, would you vote for the Democratic candidate in your district or the Republican candidate?”

Fortunately, the Times asked this of both likely voters and registered voters at the same time. Here are the responses:

| Population Sampled |

Democrat |

Republican |

Tea Party |

Other |

Unsure |

| Likely Voters |

43 |

42 |

1 |

2 |

12 |

| Registered Voters |

47 |

43 |

1 |

3 |

6 |

Even when considering registered and likely voters, we see a slight Republican bias in the likely voter response. Of course, the differences are small and close to the poll’s margin of error, so we can’t be sure the difference is driven by the different population samples. But we can’t dismiss it either. More generally, if you look at the dozens of polls that have asked versions of this “who will you vote for?” question this year, Republicans do better in surveys of likely voters versus registered voters, and better among registered voters than among all adults. You can see for yourself here, by looking at the specific polls under the 2010 midterm section.

Now, let’s return to the original numbers on which Klein based his graph. The first table has the results for the question “who do you trust to make the right decision” asked of all adults.

| Date |

Democrat |

Republican |

Both |

Neither |

No Opinion |

| 7/11/10 |

42 |

34 |

3 |

17 |

5 |

And here are the percentages of the responses to “who do you trust to handle the economy?” again asked of all adults. (Respondents favoring Democrats in the first column, those favoring Republicans in the second. I’ve omitted the “just some” and “not at all” categories to be consistent with Klein’s chart.)

What happens if you shift the net results to these two questions, say, about 5% toward the Republicans, which is consistent with the likely impact of surveying registered voters, as opposed to all adults? Suddenly, given the 4% margin of error, Republicans are virtually tied with Democrats in terms of which party is preferred by voters for handling the economy, and for making the right decisions. That is, the findings Klein cites in his chart that shows Republicans and Democrats in a dead heat in terms of registered voters’ preferences in the 2010 midterms seems quite consistent with the survey results for these two questions.

My point isn’t that Klein is wrong. In fact, the public could be acting illogically by voting for the party they trust least to handle the economy or to make the right decisions. However, the difference he cites might just be a function of sampling different populations. We can’t be sure. If I’m Klein, I would likely point this out rather than present a chart in a way that implies the public is, as one person commenting put it, “Stupid.”

I should be clear: I’m not accusing Klein of any chicanery here. It’s possible he didn’t notice that his first two survey responses were based on samples of all adults, while the third was based on a sample of registered voters. More likely, in my view, is that he saw the chance to flag an “Aha!” moment, which makes for a good column, and simply didn’t bother checking the underlying data. Whatever the explanation, it is a reminder (yes, I know, you’ve heard it from me a thousand times) that you can’t simply take a columnist’s word about how to interpret polling results. You have to look at the poll itself.

Bottom line? A chart may be worth a thousand words – but sometimes it doesn’t say anything at all.