It is telling, I think, that although Hillary Clinton continues to have a substantial lead over her Democratic rivals in national polls, media pundits are openly wondering whether her recent drop in those polls suggests, as one critic it, “It might be time to start panicking.” In the latest Huffington Post aggregate polling average, Clinton receives about 44% support, which leads her nearest rival Bernie Sanders by 18%. Meanwhile, although Donald Trump does slightly worse, comparatively speaking, in the Republican national nominating aggregate poll than Clinton does in the Democratic race – he is at about 33% in national polling averages, also 18% ahead of his closest rival Ben Carson – no one seems to be suggesting that he start panicking. Instead, the talk remains about how he continues to defy expectations. Yes, I understand the news coverage is driven as much or more by perceived polling trends as it is by absolute levels of support and polling margins. But if we do focus on trends, isn’t it also worth noting that Bernie Sanders’ national polling support has basically flattened out during the month of September? Clinton does not seem to be losing support to him of late as much as she is to the “undecided” category and to Vice President Joe Biden, who is undergoing his own “discovery” phase right now despite not formally committing to running. More generally, relative to their contenders, would one rather be in Hillary’s polling position right now, or The Donald’s?

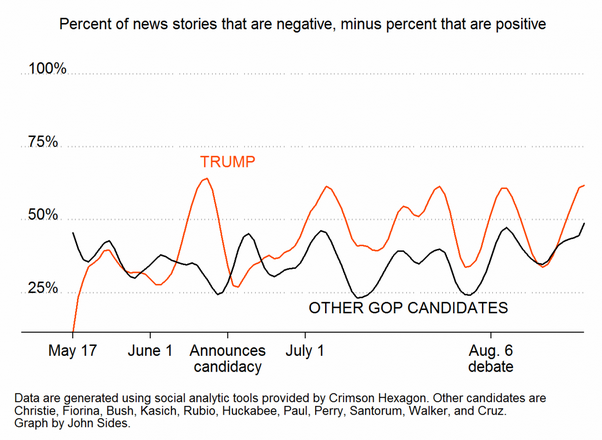

Poll results this early, of course, are not very indicative of who is likely to win the nomination, as I’ve pointed out elsewhere. And state polling is probably a more useful measure of candidate viability than are national polls in any case. Nonetheless, if the media persists in reporting on national polls, they might try harder to put these numbers in a more realistic context. Of course, this has been a problem with the media’s coverage of Trump more generally, a point that David Uberti makes in a very nice piece he wrote for today’s Columbia Journalism Review. While acknowledging that the media’s disproportionate focus on Trump is partly responsible for his staying power atop the polls, Uberti points out that Trump’s ability to drive media coverage through his recurring rhetorical firebombs and personality-driven campaign tactics makes it harder for journalists to cover him as they might a more traditional candidate. As he writes, “When the press does attempt to hold Trump accountable, he parries and pivots to highlight his strengths, however abstract.” This is not to say that Trump hasn’t received his fair share of negative media coverage. As this graph by John Sides indicates, the proportion of negative news coverage, at least through August, is greater for Trump than for the other Republican candidates.

But much of that negative coverage has focused on his personal attacks on other candidates and his outlandish pronouncements which don’t seem to matter nearly as much to potential voters as they do to journalists. And it has been counterbalanced by the media’s usual focus on the horserace numbers, which right now show The Donald trumping the Republican field. It is no wonder that as Trump’s polling numbers went up we’ve seen a steady climb in his favorable ratings over the last two months as well, despite the negative news coverage.

It is tempting, of course, to argue that rather than the outsized media coverage, Trump’s support is instead driven by unprecedented voter anger at the political establishment. But to quote one wise media pundit, “I have two words for that theory: absolutely ridiculous.” The fact is that anti-incumbent fervor has been running particularly strong for at least the last three election cycles, if not longer. And in terms of right track/wrong track measures, polls indicate voters were more bearish on the country’s future four years ago than they are today.

Similarly, trust in government was also lower four years ago. In short, this doesn’t look like an unusually angry group of voters, at least not by recent standards. Of course, even if overall levels of voter anger aren’t any higher, much of it might be disproportionately fueling The Donald’s campaign. But, as John Sides points out, it is hard to see why this would explain changing levels of support for Trump.

If, as I believe, Trump is largely a media-enabled political phenomenon, how might journalists adjust their coverage to balance their very understandable desire to cover “newsworthy topics” (read: ratings generators) with a more accurate and useful assessment of his candidacy? One way is to put polling results in a better historical context, a point I made to Uberti. A second way, as I suggested in this earlier post and again in Uberti’s article is to press Trump to go beyond broad policy pronouncements (“I will build a yyuuge wall”) to focus on specifics – how does he intend to remove 11 million undocumented immigrants? A third way, as Greg Sargent points out in his Morning Plumline post today, is for journalists to spend more time focusing on the structural impediments built into the political system that have made it so difficult for previous presidents to work with Congress in areas like government spending, immigration and entitlement reform. How does Trump propose to overcome the partisan polarization and gridlock that characterizes Congress today? Does he understand the very real limits on presidential power – limits that have stymied previous presidents who took office promising to change the Washington, D.C. political culture? In short, why should we believe he would be any more effective than previous presidents in getting things done? It’s not difficult to do this. For example, instead of asking The Donald about why he didn’t correct a questioner at a Trump rally who believes Obama is a Muslim, why not ask him what he will do differently from presidents Bush and Obama to get immigration reform legislation passed?

It is easy for pundits to characterize most Republican voters as a bunch of angry, gun-toting, bible-thumping xenophobic no-nothings. The truth is, however, that for all the media coverage of Trump’s standing atop the polls, about 70% of Republicans haven’t bought into his candidacy. Frankly, this does not surprise me. When I watch Republican campaign events and listen to the questions voters ask candidates, and when I talk to them later, most are genuinely interested in the details of what those candidates have to say, whether it is solving the immigration problem or creating jobs or dealing with ISIS, than they are about the Donald’s pronouncements regarding Carly Fiorina’s looks. Yes, voters are angry, although perhaps no more so this election cycle than in previous years, and yes, some of that anger may have led them to take a longer initial look at Trump (and other nonpoliticians) than he might otherwise have received. But the simple truth is that by focusing on what Uberti aptly describes as “Trump’s blowhard improvisation”, and failing to place polls in their historical context, the media has both contributed to his polling support and made it far easier for Trump to avoid answering the difficult questions regarding the specifics of his policy beliefs, and how he proposes to implement them. This does a disservice to voters and, I think, to Trump himself. If journalists are content to generate media ratings by focusing on the more circus-like aspects of Trump’s improbable candidacy, he has very little incentive to change his game plan. And we are all the worse off because of it.