This weekend the WayBack machine takes us to 1979 and an inside look at archival documents from Jimmy Carter’s White House during a particularly volatile time in his presidency, when he struggled to deal with the fall of the Iranian government under the Shah Pahlevi – a situation not dissimilar to what President Obama is confronting in Syria and Iraq today. As you will see in the document below, Carter’s difficulties were exacerbated by divisions within his own administration regarding the proper strategy to follow in dealing with the Iranian Revolution – and the willingness of his Iranian experts, particularly in the State Department, to use media leaks to force policy in their preferred direction.

As always, some background is in order. Beginning in late 1978 into 1979, Iran was in the throes of revolution against the repressive regime of Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlevi. Although Carter had taken office in 1977 promising to push human rights on a global basis, for geopolitical reasons the President valued the Shah’s leadership despite his authoritarian ways. Iran generally had good relation with Egypt and Saudi Arabia, and it had provided oil to Israel at a time of the Arab boycott. And, not least, Iran shared a 1,500-mile border with the Soviet Union which appeared increasingly willing to flex its foreign policy muscles. (Recall that the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan at the end of 1979).

For all these reasons, despite growing civil unrest in Iran, Carter was initially eager to see the Shah remain in power, backed by the Iranian military. In a trip to Iran at the end of 1977, Carter toasted the Shah, and called Iran “an island of stability in one of the more troubled areas of the world.” But as it became clear a year later that the Shah was losing control, and that some of the opposition to his regime was beginning to coalesce behind the radical exiled cleric the Ayatollah Khomeini, Carter faced a dilemma – one not dissimilar to what Obama faces today in Syria and Iran – regarding how deeply to become involved in Iranian domestic affairs. Should he go all in to prop up the Shah in the hope that the autocratic leader, with military support, could lead a transition to a more moderate and democratic government? Should he allow (or even implicitly suggest to) the Shah to crack down on the dissidents? Or should he leave Iran to its own affairs, and risk watching the strategically-situated nation fall under the control of Khomeini and his clerical supporters, with uncertain consequences?

It didn’t help that his advisers were split on the issue. William Sullivan was Carter’s Ambassador to Iran at the time, and although he initially advocated backing the Shah, by November 1978 he was pushing Carter to force the Shah to negotiate with opposition leaders. By the end of the year, despite the Shah’s effort to mollify the opposition by establishing a civilian government that actually had some power, it was increasingly clear that he had to step down. The Shah was reluctant to do so, however, and at the end of 1978 he appointed a relative moderate, Shahpour Bakhtiar, as Prime Minister. Bakhtiar, hoping to shore up his support with the opposition, immediately called for the Shah to leave Iran. The Shah argued that he should do so on his own timetable and Carter agreed, hoping to gain time for Bakhtiar, backed by the Iranian military, to solidify his position. However, at this point Ambassador Sullivan advocated a more complete break with the Shah, and an effort to open up a direct dialogue with the exiled Khomeini.

Carter began suspecting, as he notes in his memoirs Keeping Faith, “deviations within the State Department from my policy of backing the Shah while he struggled to establish a successor government.” As a result, and with the backing of his Secretary of Defense Harold Brown, Carter sent a military envoy, General Robert Huyser to Iran, ostensibly to keep Carter informed regarding Iran’s military needs. Eventually Carter asked his Secretary of State Cy Vance to remove Sullivan, but Vance convinced him Sullivan’s withdrawal would further destabilize the situation in Iran. However, Carter no longer trusted Sullivan to support the President’s policies and he increasingly relied on Huyser as his source of information and conduit to the Iranian government. Moreover, he was backed in his efforts to prop up the Shah by his national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski (you know – Mika’s dad). In his memoirs Power and Principle, Brzezinki argues that once the Iranian crisis “had become a contest of will and power, advocacy of compromise and conciliation simply played into the hands of those determined to effect a complete revolution.” This hard-line message, he suggests, was not adequately conveyed by the State Department.

At this point, with unrest growing, the Shah finally left Iran and, on February 1, Khomeini flew into Teheran, while Bakhtier struggled – ultimately unsuccessfully – to retain some authority. With the country seemingly on the brink of civil war Carter brought Huyser back to the White House to brief him on the situation, where Huyser informed the President that Sullivan’s interpretation of American policy differed greatly from Huyser’s. In his memoirs, Carter writes that after meeting with Huyser, “I became even more disturbed at the apparent reluctance in the State Department to carry out my directives fully and with enthusiasm.”

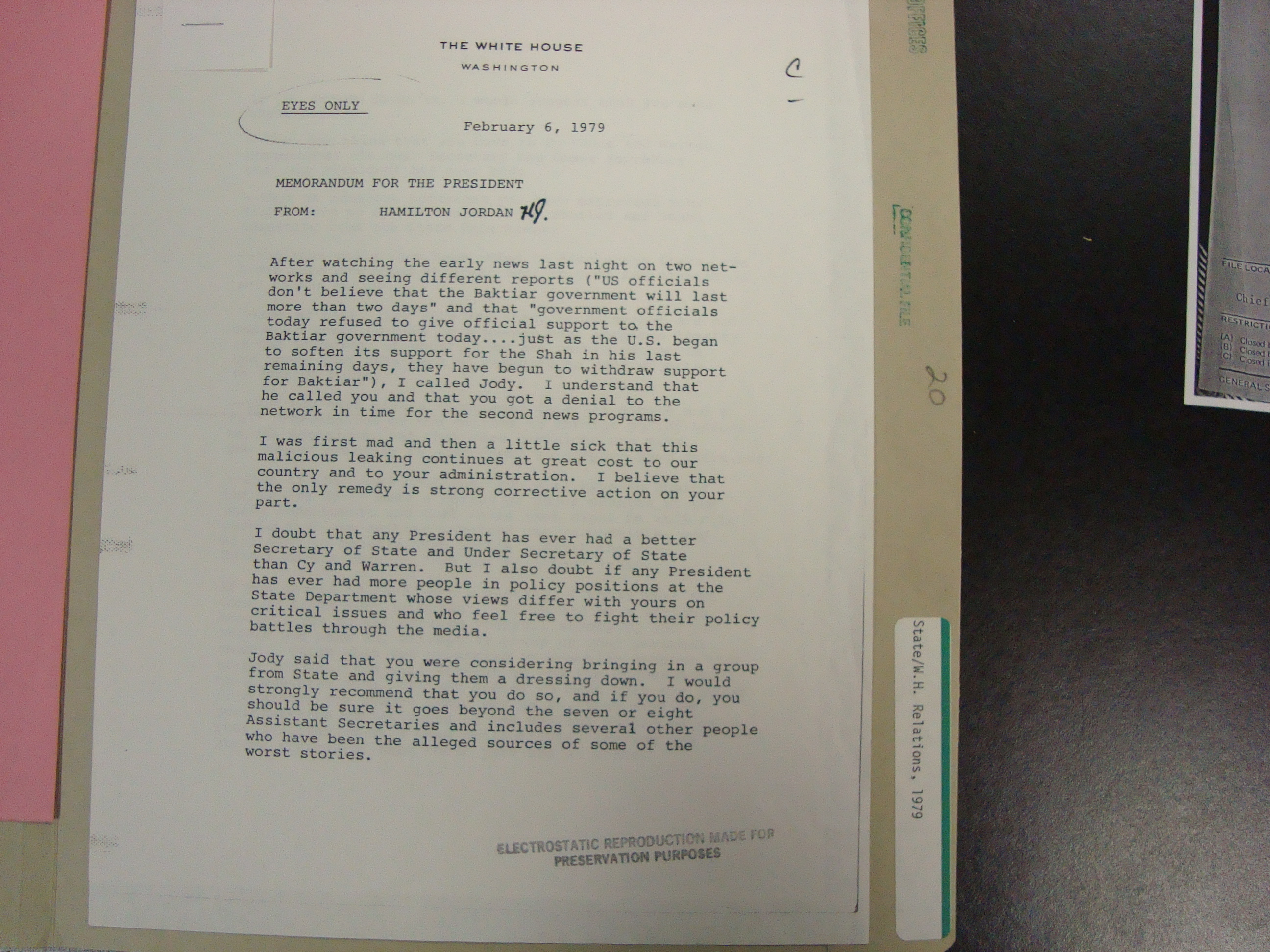

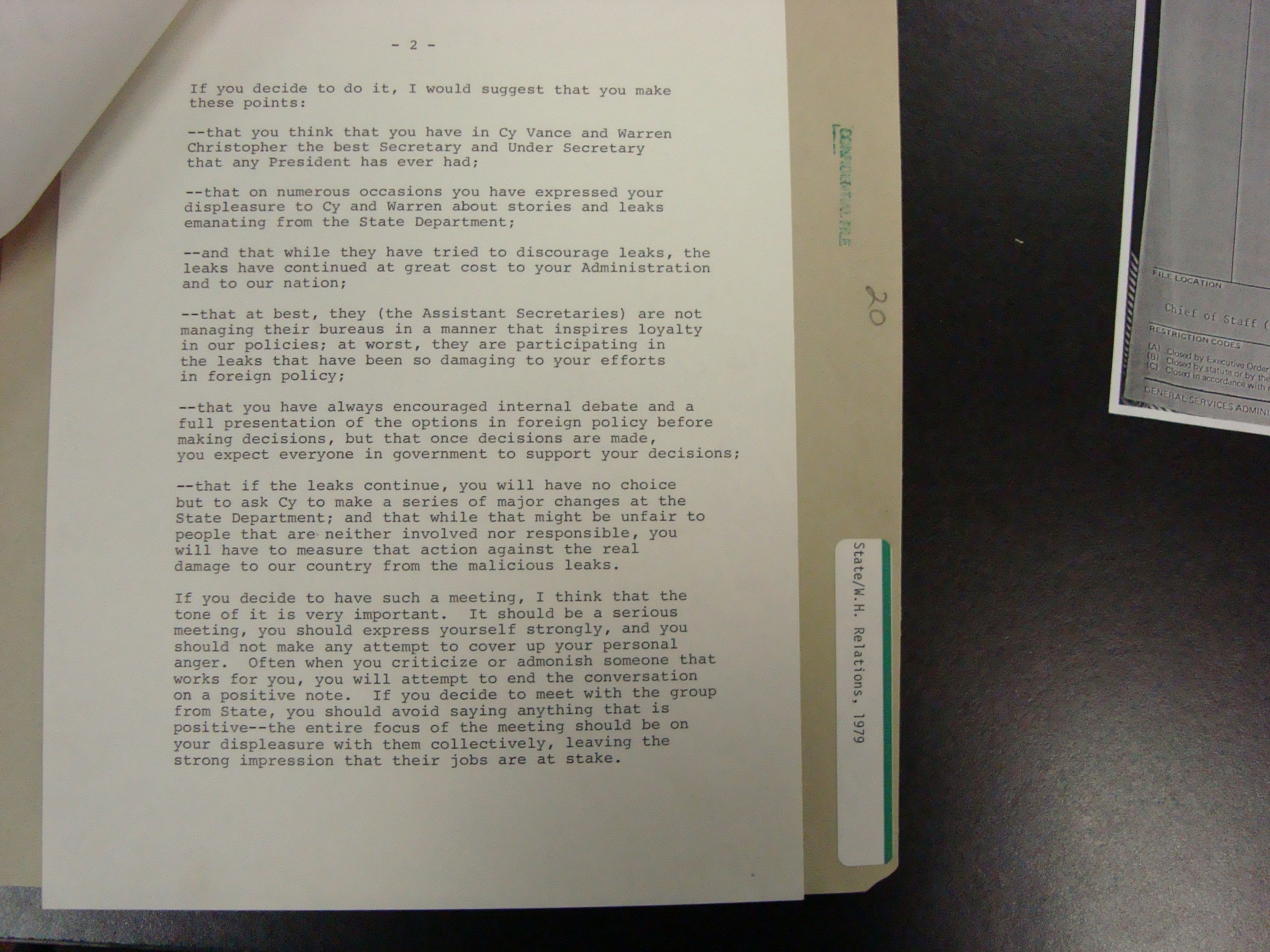

He was not the only one. On February 6, 1979, Carter’s chief White House aide Hamilton Jordan drafted this confidential “eyes only” memorandum for the President. As you can see, Jordan expresses his anger, particularly at State Department officials, for “this malicious leaking [that] continues at great cost to our country and to your administration.” Jordan goes on to recommend that Carter meet directly with State Department officials to warn them that unless the leaking stops, there will be repercussions. Toward this end Jordan concludes the memo with this: “[Y]ou should avoid saying anything that is positive—the entire focus of the meeting should be on your displeasure with them collectively, leaving the strong impression that their jobs are at stake.”

Carter took Jordan’s advice. In his memoirs he recalls asking the State Department Iranian desk officers and others to come to the White House. There Carter “laid down the law to them as strongly as I knew how…There had been a stream of news stories in Washington, seeming to originate with those who opposed my judgment that we should give our support to the Shah, to the military leaders, and later to Bakhtiar. I told them that if they could not support what I decided, their only alternative was to resign….I….repeated that they would have to be loyal to me or resign.”

The dispute of how to deal with the Shah was just one clash of many between Carter’s State Department under Cy Vance and Brzezinski’s national security team. Vance eventually resigned in protest over Carter’s decision to attempt a secret mission to rescue Americans held hostage by the Khomeini-led Iranian government – a mission that Brzezinski not only backed, but which he wanted combined with a retaliatory military strike.

In Carter’s diary entry from Feb. 7 (as reprinted in his memoirs) the President placed part of the blame for the differences between State Department and NSC officials on the news media which “constantly aggravate the inevitable differences and competition between the two groups.” But the differences run deeper than a media-driven effort to fan the flames of controversy. They reflect an ongoing tension between a president’s need for expertise and his desire for loyalty. To fully reap the benefits of aides’ expertise, presidents must give those specialists the freedom to disagree, and to propose and actively argue for policies that a president may oppose. Of course, it is the case that many specialists well-versed in their field and who truly believe that their advice is in the best interests of the nation are going use multiple tactics to make sure that message is heard by decisionmakers – including selective leaking via the press. And just as inevitably, presidents and their closest White House advisers are going to see these leaks as signs of disloyalty. In the end, when faced with dueling recommendations, presidents typically choose loyalty over expertise. It is one reason why, as I’ve discussed previously in this post regarding Hillary Clinton’s nomination as Secretary of State, that over time presidents tend to rely more on their NSC staff, and often grow increasingly skeptical of the advice they get from State. For presidents, the foreign policy establishment often seems more sympathetic to the interests of the countries in which they are stationed than they are to the president’s perspective.

However, to the extent that efforts to stifle leaks and close ranks cuts presidents off from contrary advice, it is a tendency that should be resisted – even if it means tolerating public reports of internal dissension. I have no doubt that we are seeing this type of selective leaking by foreign policy experts within the Obama administration now, as Obama struggles to fashion a policy for fighting the Islamic State and for dealing with civil unrest and war in both Iraq and Syria. And Obama appears no happier about it than Carter did. Of course, journalists have been complaining for some time that the Obama administration’s efforts to prosecute leakers is having a chilling effect on investigative journalism. Such arguments, coming from journalists, are unlikely to exercise much sway with the President, particularly when the administration feels these national security leaks break the law.

I would argue, however, that even efforts like Carter’s that fall short of legal prosecution, but nonetheless are designed to tamp down dissent, are potentially costly for the President. The reason is that they run the risk of reducing the willingness of specialists to convey advice that the President and his closest aides are not initially inclined to hear. Sometimes those specialists can’t be sure that their advice is reaching the President, and hence they use alternative channels, including the media, to make certain their views are known and to encourage a more robust debate regarding policy options. Understandably, the President hopes to keep that dissent in house, in order to provide a united front to the public and other audiences who are watching for signs regarding what the President will do. Just as understandably, specialists – particularly those who feel cut out of the decisionmaking process – may choose to make their views known through alternative means.

No president likes dissent, particularly when it is expressed through media leaks. In his memo to the President, Jordan asserts, “I … doubt if any President has ever had more people in policy positions at the State Department whose views differ from yours on critical issues and who feel free to fight their policy battles through the media.” I’m willing to guess that, contrary to Jordan’s claim, almost every president in the modern era feels they confront the most damaging leaks. But those leaks are the inevitable byproduct of governing in a system in which political actors, responding to their own incentives and from different vantage points, must collaborate to make policy, and presidents should accept them as the cost for encouraging productive debate.