Last week Larry Summers announced that he would resign as director of President Obama’s National Economic Council (NEC) after the upcoming midterm elections. As the head of the NEC, Summers – working from his West Wing office – served as Obama’s primary economic adviser and was largely responsible for coordinating the administration’s economic policy process. As such, he played a key role in the major economic policy debates that led to the stimulus bill and legislation overhauling the nation’s financial system, among many issues. Following on the heels of the earlier resignations by Obama’s OMB director Peter Orszag and his CEA chair Christina Romer, Summers’ departure means that only Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner remains from the economic policy team with which Obama began his presidency (not counting the Fed chair, of course).

It is tempting to read Summers’ resignation as a sign that Obama is revamping his economic team and possibly his policies in the face of a stubbornly high unemployment rate and the more general economic listlessness. Publicly, Summers’ decision to leave is being portrayed as a personal choice motivated by his desire to get back to Harvard. That may very well be true. But the timing of the announcement almost certainly reflects Obama’s realization that the midterm results, now less than two months away, will turn largely on voters’ perceptions of Democrats’ handling of the economy. And while Obama can do little to change the economy between now and November, he can signal to voters that he is open to new economic advice and ideas.

Both progressives and conservatives have been unhappy with Summers’ performance, albeit for different reasons. Their dissatisfaction, however, is a reminder of just how complex – substantively and politically – the economic problems Obama inherited are, and how difficult it is to design policies that can entail even marginal economic improvements without incurring huge political costs. Rather than as an opportunity to debate Obama’s economic policies, however, I want to use Summers’ resignation to illustrate another important point: that turnover rates among the presidents’ senior policy staff have gone up in the last several decades, potentially making it more difficult for presidents to sustain politically-risky policy commitments.

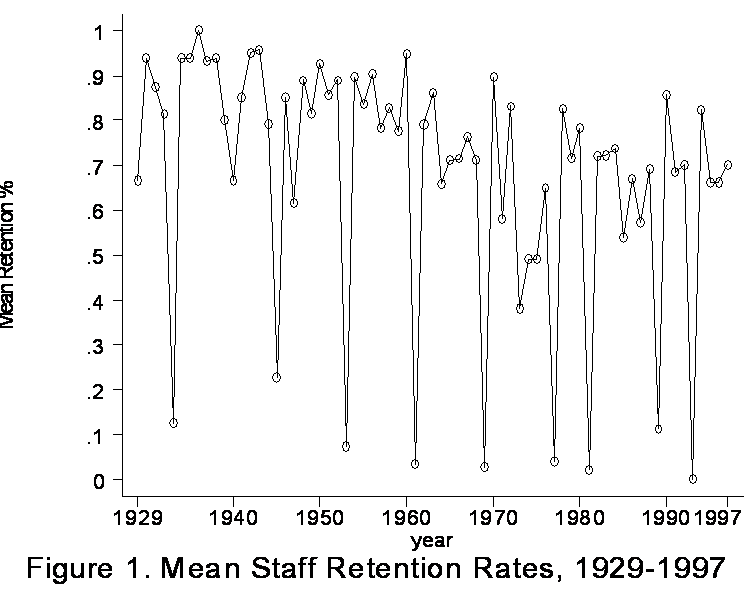

The trend toward shorter staff tenures as illustrated in the almost complete turnover in Obama’s senior economic team, I believe, is rooted less in the personalities or policies of particular presidents and their advisers, and is due more to changes in national politics during the last several decades. I first made this argument several years ago in two published research articles I co-authored with Professor Katie Dunn Tenpas. Those articles documented a gradual but noticeable decline in retention rates among the presidents’ senior White House staff and leading cabinet officials during the period 1929-96 – a decline illustrated in the following graph. (Note that the lowest retention rates reflect the transition to new presidents.)

As you can see, there has been a decline in retention rates across the nearly seven-decade period, particularly since the 1960’s, punctuated by nearly complete staff turnover when a new president comes aboard. What explains this decline? It is tempting to think that it is a function of the increased workload that modern presidential staffs take on, which leads senior advisers to burn out more quickly. However, there is not much evidence that aides are worker harder or for longer hours today than they did back under FDR or Truman. In my interviews and research with former White House aides, some dating back to the Truman presidency, the recurring story is the same: long hours at the office, with almost no time off. For example, Ken Hechler, a former Truman junior White House aide, remembers how at the end of the day a group of junior-level White House staff would collapse into a single car and fall instantly asleep, to be woken only when the car arrived at their respective residence. One by one they would be dropped off, only to start the process all over again early the next day. Work at the White House, it appears, has always entailed long hours and little sleep.

If senior officials aren’t working longer or more arduously, then what explains the declining retention rates? Tenpas and I hypothesize that it partly reflects the changing political environment within which presidential aides work. In particular we cite the change from a party-controlled election process to a candidate-centered one. Increasingly, presidents are running their reelection campaigns from out of the White House, rather than entrusting this function to the party chair and his minions, as used to be the case. Rather than oversee the reelection campaign, the party instead has been relegated to serving primarily as a fundraiser, while strategy and tactics are developed by the President’s personal staff, working out of the White House. (Note that because by law purely electoral activities cannot be paid for from out of the White House operating budget, White House aides have to take care to separate the two functions). At the same, there is anecdotal evidence suggesting that the increasingly polarized nature of presidential politics makes service in the White House less enjoyable. I don’t have systemic evidence to bring to bear on this issue, but more than one former White House adviser from recent presidencies has made this point to me. Decisionmaking, they say, is increasingly driven by electoral concerns.

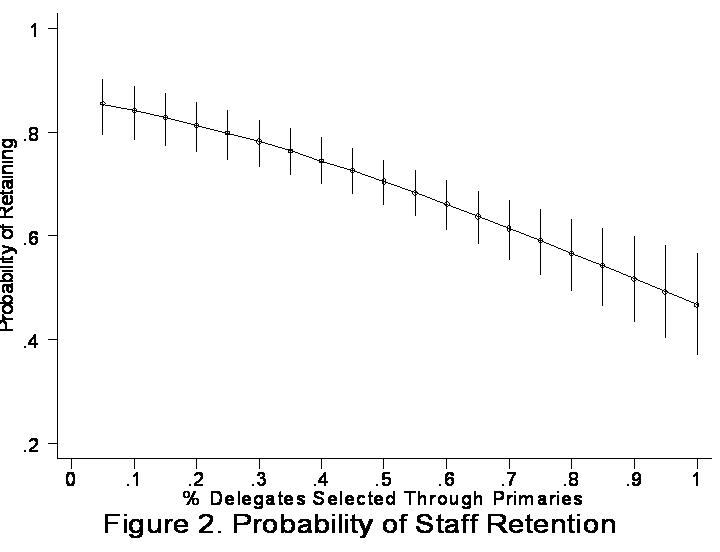

The change in the nature of presidential campaigns, and of the operating environment more generally, is probably best illustrated by the rise in the role of primaries during the nominating process, beginning particularly after 1968. Why does this affect the president’s senior staff? Because by essentially the end of the president’s second year in office, he must begin campaigning for reelection. This is when the substantive policy types who are so important for governing begin to leave the White House. To see this, in the next figure I’ve graphed retention rates as a function of the growth in the number of delegates selected through primaries.

Note that as the percent of delegates selected through primaries goes up, staff retention rates decline. (The bars around each mean measure the uncertainty of the estimate). Viewed historically, then, the resignation of Obama’s major economic advisers is neither unprecedented nor surprising. On average, in the period 1972-1996, only about 75% of a president’s senior cabinet and White House advisers are retained from the first year of the president’s term into his second year, and only 64% of second-year staffers make it to the third year. This compares to a roughly 85% retention rate for both presidential years during the pre-1972 era. I’ll try to update these figures through 2008 if I can, but I hope my point is clear: life in the White House is a Hobbesian existence (and I don’t mean Calvin’s imaginary friend): nasty, brutish – and increasingly short.