It’s Sunday, and that means time for some short takes on trending stories:

In this earlier post I argued, tongue only partly in cheek, that Hillary Clinton may not be rich enough to be a great president. As I pointed out, our greatest presidents as rated by historians are, beginning with George Washington, often extraordinarily wealthy. Indeed, wealth seems to be a predictor of greatness! Despite this, I noted a spate of media stories of late suggesting that Hillary’s wealth may somehow prove to be a stumbling block for the presidency. Not surprisingly, given this narrative, Republican Party operatives have established a website designed to make Clinton’s wealth a campaign issue.

That Republicans are using Clinton’s wealth against her does not surprise Democratic pundit Paul Waldman. However, that the media seem to embrace the same logic does surprise him. As he writes in this Washington Post opinion piece, “But what may be even more remarkable is that so many in the press go right along with this stupidity… There’s a hidden assumption in some of this coverage that candidates should be nothing more than advocates for their class. If you’re rich, then you can’t sincerely care about the well-being of people who aren’t, and anything other than advocacy on behalf of other rich people is odd, even suspect.” The irony here, of course, is that Waldman’s Democratic colleagues used precisely this logic to attack Mitt Romney’s candidacy during the 2012 campaign.

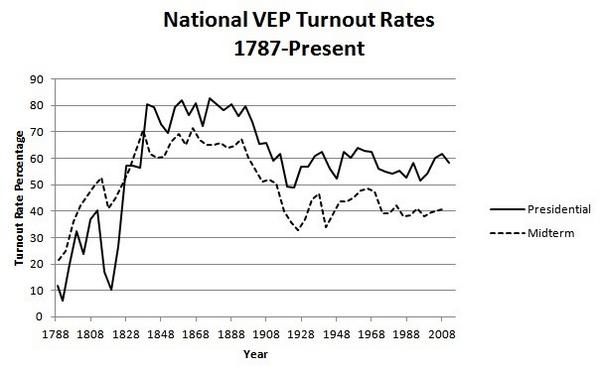

Meanwhile, in an otherwise illuminating discussion of the reasons why midterm election turnout is typically much lower than that for a presidential election campaign, Pew Research Center author Drew DeSilver posted this graph based on research by Michael McDonald, a University of Florida political scientist:

As you can see, turnout out for congressional midterm elections was actually higher than for presidential elections during the period 1789-1824, which runs contrary to the norm for most of our nation’s history. What explains this apparent anomaly? DeSilver’s answer: “History break: As McDonald’s chart shows, in the early decades of the republic, midterm elections typically drew more voters than presidential contests. Back then, most states only gave voting rights to property owners, and Congress — not the presidency — tended to be the federal government’s main power center and focus of electoral campaigns.” What DeSilver’s explanation does not say, however, is that for the first several presidential elections, many states did not choose electors through the popular vote. In 1792, for example, George Washington won reelection, but only 6 of the 15 states chose electors based on some form of popular input. It is no wonder, then, that turnout for congressional elections was higher – many people simply did not have the opportunity to vote for the president (or, more properly, for the electors who chose the president). Indeed, it was only after most states began using the popular vote as a means of choosing electors, along with a decline in property-based voting requirements, that popular participation in presidential elections began increasing. That increase in participation provided presidents, beginning with Andrew Jackson in 1828, with an independent base of power and rescued the office from a dangerous dependency on Congress.

Peter Rothschild brought the following Security Weekly article on immigration by Scott Stewart to my attention. You might think, given the extraordinary media attention to the immigration issue, most recently in reaction to Texas Governor Rick Perry’s decision to post the National Guard at his state’s border with Mexico, that we are facing a record influx of illegal immigrants. Think again. Stewart writes, “Lost in all the media hype over this ‘border crisis’ is the fact that in 2013 overall immigration was down significantly from historical levels. According to U.S. Border Patrol apprehension statistics, there were only 420,789 apprehensions in 2013 compared to 1,160,395 in 2004. In fact, from fiscal 1976 to 2010, apprehensions never dropped below 500,000. During that same period, the Border Patrol averaged 1,083,495 apprehensions per year compared to just 420,789 last year.”

Of course, as Stewart acknowledges, apprehensions may not be the best indicator of the rate of illegal border crossings. Still, the data seems to belie the media narrative that the country is enduring an illegal immigration crisis. But it is easy to lose sight of this with the media focus on the apparent increase in undocumented children crossing the border. That story has far greater media legs than does one focusing on the fact that “the Border Patrol will apprehend and process hundreds of thousands fewer people this year than it did each fiscal year from 1976 until 2010.”

Finally, we are scheduled to begin occasional “simulposting” with the Christian Science Monitor sometime this coming week. If past experience is any clue (see the comments to this post on the debt ceiling crisis!), the more visible platform is likely to mean more comments from readers who often have strongly-held views. That’s fine – I always enjoy the comments from readers from both sides of the political aisle and try to respond to all of them. I also exercise a very light touch on the censor button – as long as the comments are civil, I don’t care how passionate the language or what political views are expressed, although it is worth reminding everyone that my response to a comment doesn’t necessarily imply agreement (or disagreement) with that comment. This is a non-partisan blog – it says so right in the title! I learn a lot from readers, and my hope is that we can continue this dialogue in the months to come.

Have a great Sunday!