The presidential press conference dates at least back to Woodrow Wilson’s presidency in 1913, although the modern incarnation is of more recent vintage; beginning in 1961, JFK was the first president to hold live, televised conferences. Every president has followed JFK’s lead, but with diminishing returns for both president and the viewing public. In theory, press conferences serve a useful purpose; they allow presidents to explain their policy decisions to the public, and they provide the press, working on behalf of the public, the opportunity to hold the president accountable for those decisions. In truth, press conferences rarely live up to that promise. Reporters try to devise questions that will elicit a newsworthy response, preferably the one that will lead the media coverage and generate ratings. Presidents respond by staying on script in an effort to drive home their preferred talking point. In this elaborate game, reporters have to be careful, because if they go over the edge and appear to be overly hostile to the president, they may not get called on in the next press conference. On the other hand, reporters realize that press conferences are increasingly rare events, and with only about a dozen reporters called on at any one session, they must capitalize on their moment in the sun.

In studying press conferences, there are two trends to keep in mind. Historically, the number of press conferences is declining, as presidents find them an increasingly less useful tool for getting their message out to the public. (Eisenhower reportedly began one press conference by stating, “I will mount the usual weekly cross and let you drive the nails.”) Within any single presidency, the number of press conferences held tends to decline as well, and for the same reason. Before showing you some data on the frequency of press conferences, however, we would do well to define the term. What constitutes a press conference? Consider that before holding his evening press conferences, Barack Obama visited a town in Indiana and took questions there. Is that also a press conference? No, not by the traditional definition. Most scholars tabulate press conferences according to the following criteria:

1. It is a public event in which reporters accredited to cover the president are free to ask any question they desire – if the president calls on them.

2. The proceedings must be on-the-record, with an official transcript of questions and answers available to the public.

3. The press conference should be scheduled and announced in advance, including the location, to provide the press an opportunity to prepare questions. (White House-based press conferences aren’t always held in the East Room; FDR held his in the Oval Office, but that became impossible as the size of the press corps expanded. Some presidents still prefer the White House Briefing Room).

Using these criteria, Martha Kumar calculated the following frequencies for presidential press conferences (source here). (This data is through the second year of George W. Bush’s presidency).

|

President |

Months in Office |

Total Press Conferences |

Avg. per Year |

Avg. per Month |

|

LBJ |

62 |

135 |

26.16 |

2.18 |

|

Nixon |

66 |

39 |

7.08 |

.59 |

|

Ford |

30 |

40 |

15.96 |

1.33 |

|

Carter |

48 |

59 |

14.76 |

1.23 |

|

Reagan |

96 |

46 |

5.76 |

.48 |

|

George H.W. Bush |

48 |

142 |

35.52 |

2.96 |

|

Clinton |

96 |

193 |

24.12 |

2.01 |

|

George W. Bush (first two years) |

24 |

39 |

19.44 |

1.62 |

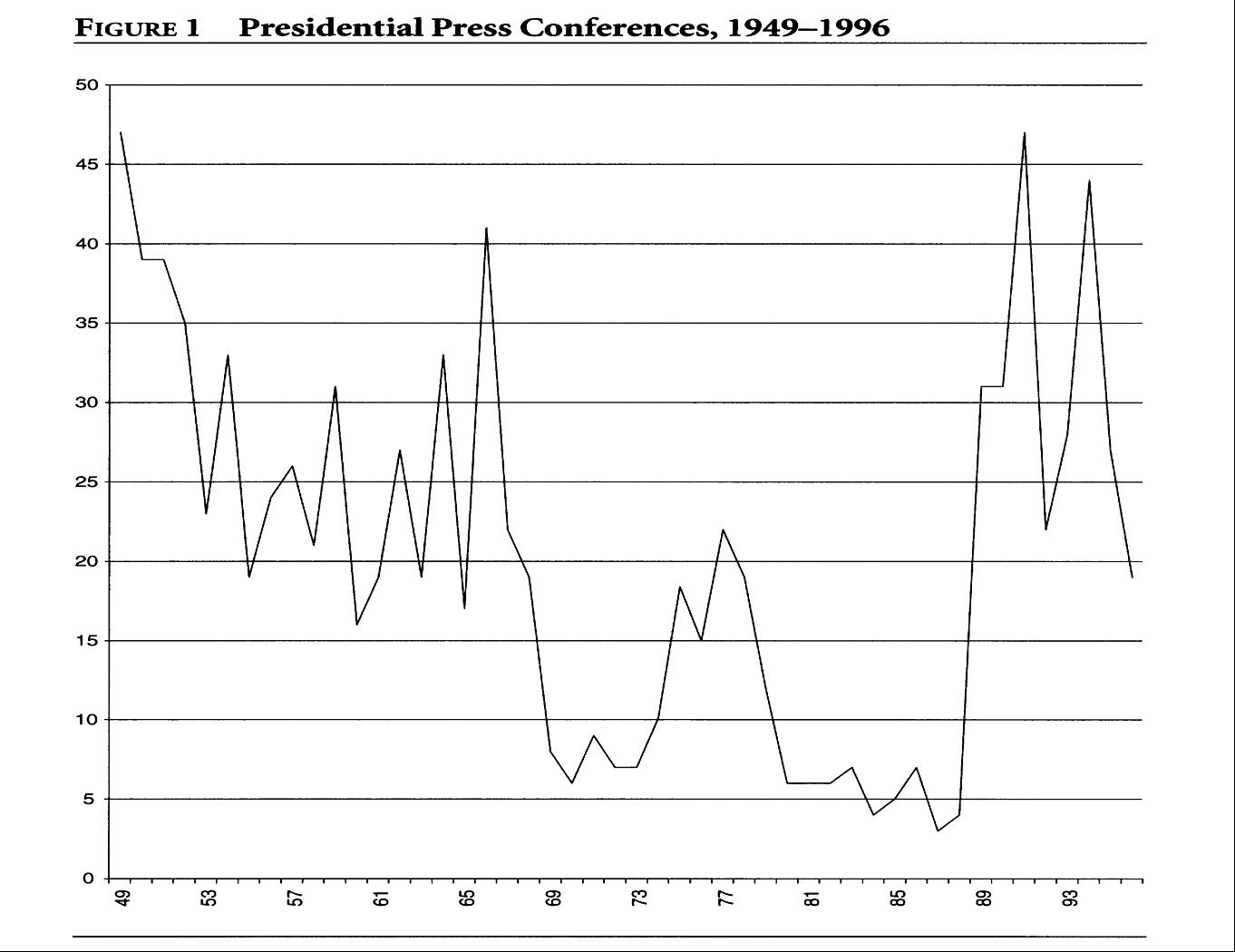

Matthew Eshbaugh Soha, in a political science journal article dating from 2003, extends Kumar’s data back to the second Truman term. Although the numbers are hard to read, what I want you to see is the huge drop in the frequency of press conferences from roughly the tail end of LBJ’s presidency through Reagan’s presidency.

As we can see, the advent of the televised press conferences beginning with JFK has contributed to the decline in the overall number of press conferences; Truman averaged about 40 press conferences per year and Eisenhower about 29. That number has declined to roughly 25 per year under Clinton and about 20 for Bush, and much lower than that under Nixon through Reagan.

Is there a way to make the press conference a useful tool of information exchange that both benefits presidents and the public? I have long argued that presidents ought to negotiate an agreement with the media to reinstitute a form of the exchange used with such great success by FDR during his presidency. Roosevelt held almost 1,000 press conferences, all under guidelines laid out in his first press conference in March, 1933. They are worth repeating here:

Excerpt from President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s First Press Conference

CONFIDENTIAL

Press Conference #1

At the White House, Executive Offices

March 8, 1933, 10:10 A.M.

(Mr. Young introduced the members of the Press to the President.)

THE PRESIDENT: It is very good to see you all and my hope is that these conferences are going to be merely enlarged editions of the kind of very delightful family conferences I have been holding in Albany for the last four years.

I am told that what I am about to do will become impossible, but I am going to try it. We are not going to have any more written questions and of course while I cannot answer seventy-five or a hundred questions because I simply haven’t got the physical time, I see no reason why I should not talk to you ladies and gentlemen off the record just the way I have been doing in Albany and the way I used to do it in the Navy Department down here. Quite a number of you, I am glad to see, date back to the days of the previous existence which I led in Washington.

(Interruption – “These two boys are off for Arizona.” [FDR’s sons] John and Franklin Roosevelt saying “good-bye”.)

And so I think we will discontinue the practice of compelling the submitting of questions in writing before the conference in order to get an answer. There will be many questions, of course, that I won’t answer, either because they are “if” questions – and I never answer them – and Brother Stephenson will tell you what an “if” question is –

MR. STEPHENSON: I ask forty of them a day.

THE PRESIDENT: And the others, of course, are the questions which for various reasons I don’t want to discuss or I am not ready to discuss or I don’t know anything about. There will be a great many questions you will ask about that I don’t know enough about to answer. Then, in regard to news announcements, Steve [Early] and I thought that it was best that street news for use of here should always be without direct quotations. In other words, I don’t want to be directly quoted, with the exception that direct quotations will be given out by Steve in writing. Of course that makes that perfectly clear.

Then there are two other matters we will talk about: The first is “background information”, which means material which can be used by all of you on your own authority and responsibility and must not be attributed to the White House . . . . Then the second thing is the “off the record” information which means, of course, confidential information which is given only to those who attend the [press] conference. Now there is one thing I want to say right now on which I think you will go along with me. I want to ask you not to repeat this “off the record” confidential information either to your own editors or associates who are not here because there is always the danger that while you people might not violate the rule, somebody may forget to say, “This is off the record and confidential”, and the other party may use it in a story. That is to say, it is not to be used and not to be told to those fellows who happen not to come around to the conference. In other words, this is only for those present.

Now, as to news, I don’t think there is any. (Laughter).”

Roosevelt used this system to great effect. Because reporters did not quote him directly unless otherwise authorized, Roosevelt felt comfortable speaking much more candidly than do presidents today whose every word is immediately transmitted live to a vast audience. At the same time, reporters benefited because they received “hard news” rather than the “message du jour” that dominates most presidential responses today. Of course, the advent of the electronic media, and the vast increase in the size of the press corps would necessitate some changes to the Roosevelt “closed” system. But it’s hard to believe that the current system of press conferences can’t be improved. For instance, can you imagine a president today, in a live news conference, saying “I don’t know the answer to that question”? He would get skewered! Under the Roosevelt system, on the other hand, FDR routinely acknowledged when he didn’t have the information, or referred an answer to an aide. How refreshing that would be today! But it’s simply not possible in the modern era, where every verbal gaffe or acknowledgment of ignorance by the President becomes a weapon to be utilized by the political opposition. It’s hard to see how the public interest is served under this system of press conferences.

With this overview, I will next look more closely at the substance of Obama’s first press conference and how it was reported by the media. By way of advance notice, however, let me say that the one thing that stood out was his ability to filibuster by giving lengthy responses. Particularly at the start of the Q&A, Obama gave elaborate, lengthy answers to questions. I thought this served two useful purposes: it ate up a lot of time, preventing other reporters from getting questions in. And – with luck – it meant that his core message would be more likely to lead the media coverage of the conference. I’m not sure how well these long answers played with the viewing audience. On the other hand, press conferences tend not to be widely viewed. I’ll see if I can get the numbers on total viewers on this one and compare it to the audiences for past press conferences.