For this Saturday’s trip to the archives we take the WayBack machine to March, 1968 for an inside view of President Lyndon Johnson’s possible reelection strategy, courtesy of an incredibly candid 10-page memo written by his White House Special Counsel Harry McPherson. I’ve written about McPherson before – he was a longtime Johnson aide who served as the President’s speechwriter/domestic policy adviser, following in the footsteps of Samuel Rosenman under FDR and Ted Sorensen under JFK. McPherson’s memoirs A Political Education are required reading for any student of the Johnson presidency.

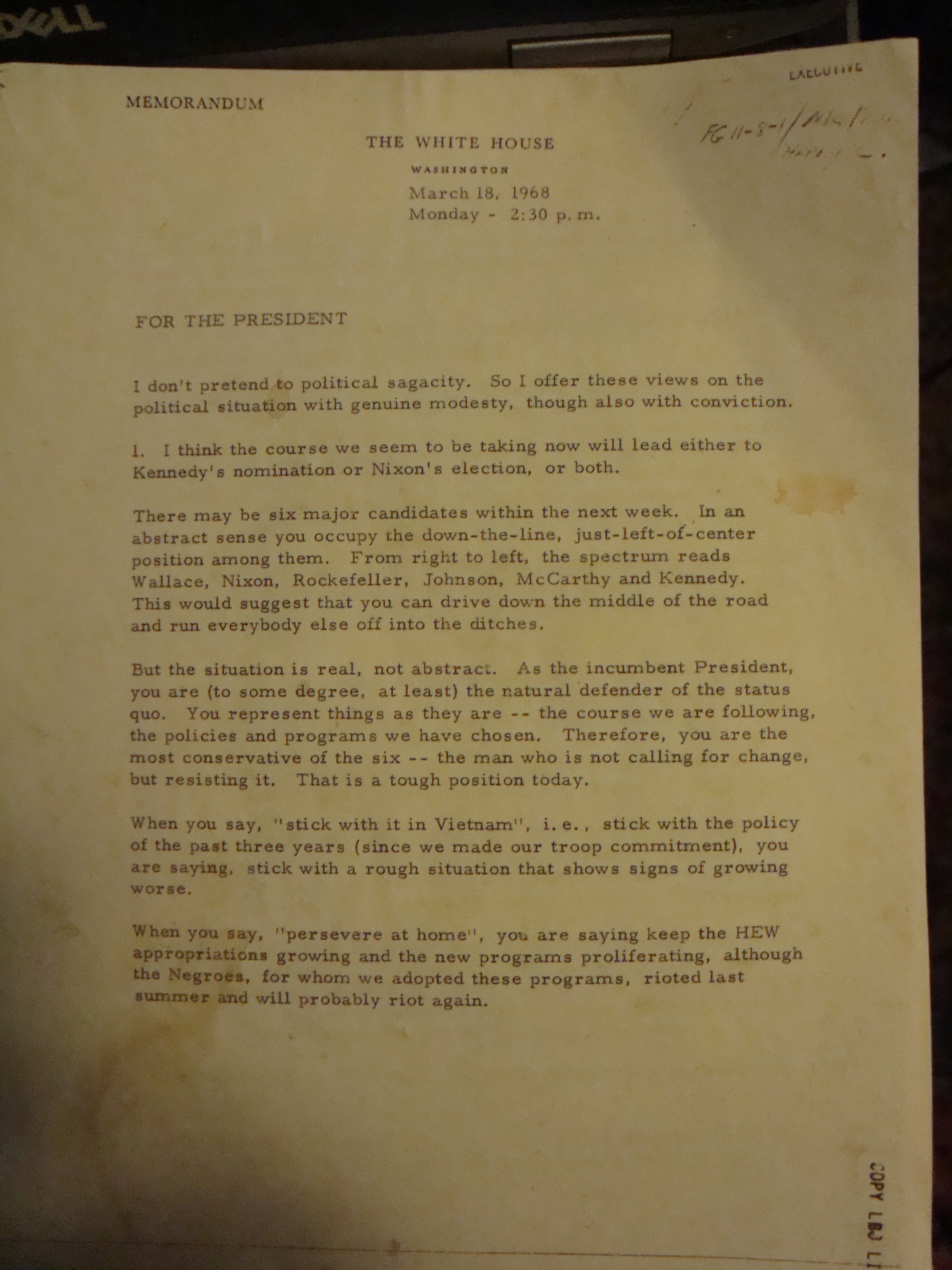

This particular memorandum was written on March 18 – a crucial time in one of the nation’s most momentous presidential races. Heading into the presidential election, it was widely assumed that Johnson would run, and likely win, a second full term. Despite growing opposition to the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, no member of his party was willing to challenge a sitting president – except for Minnesota Senator Eugene “Clean Gene” McCarthy, who decided to run on an anti-war platform. On March 12, with strong support from college students, McCarthy won a surprising 42% of the vote in New Hampshire’s first-in-the-nation primary, finishing second to Johnson’s 49%. Four days later Robert Kennedy, who had previously said he would back the President for reelection, jumped into the race for the Democratic nomination. That set the stage for this 10-page McPherson memo which laid out his strategy for Johnson’s reelection. McPherson wrote, as he stated at the start of the memo, in the belief that “the course we seem to be taking now will lead either to Kennedy’s nomination or Nixon’s election, or both.”

To prevent that outcome, McPherson argued that LBJ needed to resist the natural tendency, as the incumbent, to defend the status quo and to “drive down the middle of the road and run everybody else off into the ditches.” This was a losing strategy, McPherson thought, because it meant Johnson was easily linked, unfairly or not, to circumstances – rising crime, increased drug use, urban riots and, of course, the Vietnam War – that were of growing concern to voters.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the McPherson memo are his capsule summaries of the other candidates. On the conservative* side “Wallace offers a violently different way of doing things” while Nixon “offers a modified version of the Wallace change.” Rockefeller is the “Republican Kennedy.” As for the Democrats McCarthy “would provide a genteel, witty, and distinguished front for a pull-out” from Vietnam. Regarding Kennedy McPherson wrote “he will try to occupy the same relation to you that his brother Jack occupied to the Eisenhower-Nixon administration: imagination and vitality vs. staleness and weariness, movement vs. entrenchment, hope of change vs. more of the status quo.” (Where have we heard that before?) McPherson acknowledged that “many young liberals are bitter about [Kennedy’s] opportunistic entry into the race after McCarthy’s strong showing, but Kennedy is cynical enough to believe that they will forget, given time, razz-ma-tazz, and the development of momentum behind his candidacy. He is right about that.”

What could LBJ do to secure his nomination? “I recognize that to some degree you are the prisoner of the status quo. But there is no need to embrace your imprisonment.” Here McPherson lays out a series of policy readjustments designed to portray LBJ as “restlessly eager to change things as anyone else – and a great deal more knowledgeable about the problems involved in effecting a change.”

In Vietnam, that mean reducing the scope of U.S. involvement but also showing the enemy “that we cannot be thrown out of Vietnam”. On urban violence, he should ask his attorney general to invite 50 big city mayors and police chiefs to Washington for a conference on their concerns.

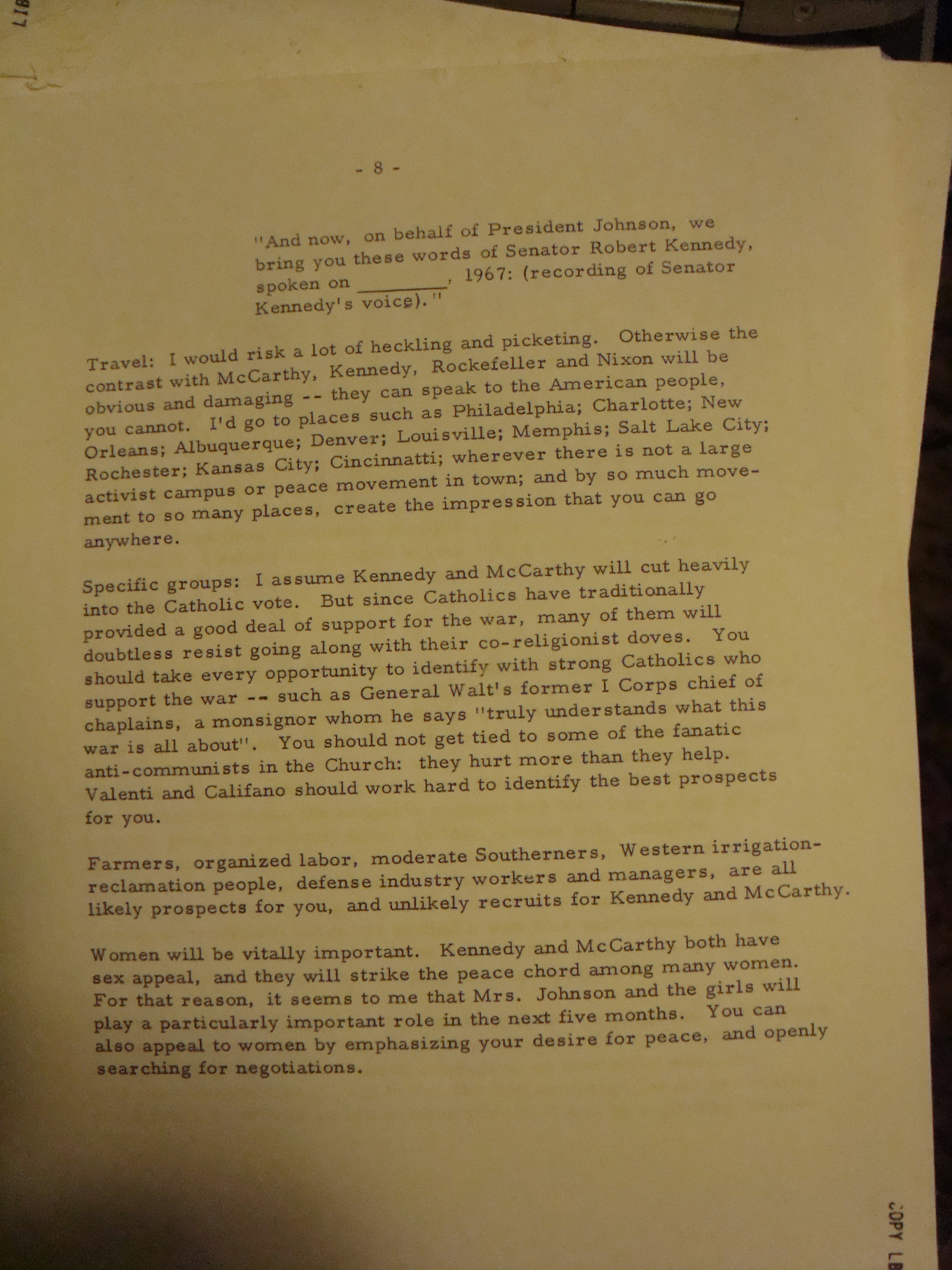

McPherson then pivots to discuss specific campaign strategy. His comments here on the Catholic vote, and on women and Kennedy’s and McCarthy’s “sex appeal” are particularly interesting:

The memo concludes with this exhortation: “Movement, candor, dissatisfaction – together with your strength, experience, and achievement – these can win it for you.”

Twelve days later Johnson made this bombshell announcement. McPherson, like all of LBJ’s aides, never saw it coming.

[youtube.com/watch?v=rYqmO0PJ5Zk]*Correction: an earlier version of this post listed Wallace with McPherson’s description of Republicans – he was a Democrat of course.