It’s been a rough presidency for Obama so far. His promise to change the tone of Washington politics proved woefully naïve in the face of a deeply polarized Congress and the echo-chamber effect of an increasingly ideologically fragmented news media. He inherited a financial bailout program and an economic recession that has stubbornly lingered despite (or because of, according to critics) Obama’s backing of a $800 billion stimulus bill. The spending on these programs, combined with the economic slowdown, has contributed to a dramatic increase in the budget deficits, dwarfing anything seen under his predecessor. More people continue to disapprove than approve of his signature domestic legislative achievement – health insurance reform – with no indication that these numbers will reverse themselves. His decision to escalate the U.S. military presence in Afghanistan, and to retain Bush-era policies dealing with military commissions, domestic eavesdropping, and other security-related policies did not sit well with his base, and he faces a difficult decision regarding how much of an American military force to leave in Iraq. It has been more than a year, and it looks increasingly like Guantanamo Prison will not close at all. And now he is grappling with the worst environmental disaster in U.S. history, with no evidence that he has any plan to solve the crisis. No wonder that the latest polls show more people disapproving than approving of his job as president. Indeed, in what some interpret as a sign of buyer’s remorse, his main rival for the Democrat nomination Hillary Clinton is now more popular than he is! All this portends bad news heading into the 2010 midterms, as Republicans paint Obama as the face of the Democrat Party while voters appears increasingly to adopt an anti-incumbent attitude.

Is there any good news for Obama anywhere? According to Peter Baumann, there is in fact a silver lining in this grey cloud.

Baumann is a 2010 political science graduate of Middlebury College who wrote his senior honors thesis on the likely impact of Obama’s 2008 election on future presidential elections. (Full disclosure: I was Baumann’s primary adviser. Bert Johnson served in his typically astute fashion as the second reader). As part of the celebrated “youth vote” that came out for Obama by almost 2-to1 in the election, Baumann was curious to see whether that support for the Democrat presidential candidate was now etched into this cohort’s political identity. That is, would the 18-29 year olds continue to vote disproportionately for the Democrat presidential candidate when they were 40 years old? Sixty-four? Did Obama establish a generational political identity? Note that there is a bevy of literature suggesting that voters become politically socialized during this young age period as they adopt partisan leanings and voting habits that thereafter gradually crystallize.

To find out what the Obama youth vote portends, Baumann looked at past presidential elections to see whether the youth vote in any given election could predict partisan support three and seven election cycles down the road. His research was complicated by the absence of individual-level voting data across this period, so he had to make do with aggregate results which pose some problems for interpretation. Nonetheless Baumann was able to tease out some interesting results.

So, is the youth vote destined to break for Democrats 2-1 in all subsequent elections? The short answer is no – one cannot expect this cohort to continue voting Democrat in such lopsided numbers in 2020, or 2036. The reason is that voters are, in Baumann’s words, “constantly adjusting their partisan identification and voting tendencies based on rational decisions about the way candidates or parties are representing their values and policy preferences.” Presidential elections, as you’ve read on this site repeatedly, are driving by the fundamentals in play at any given time. Put another way, if things have gone to hell-in-a-hand basket on a Democrat president’s watch, many Democratically-inclined voters are going to swallow their partisan inclinations and vote for the other candidate.

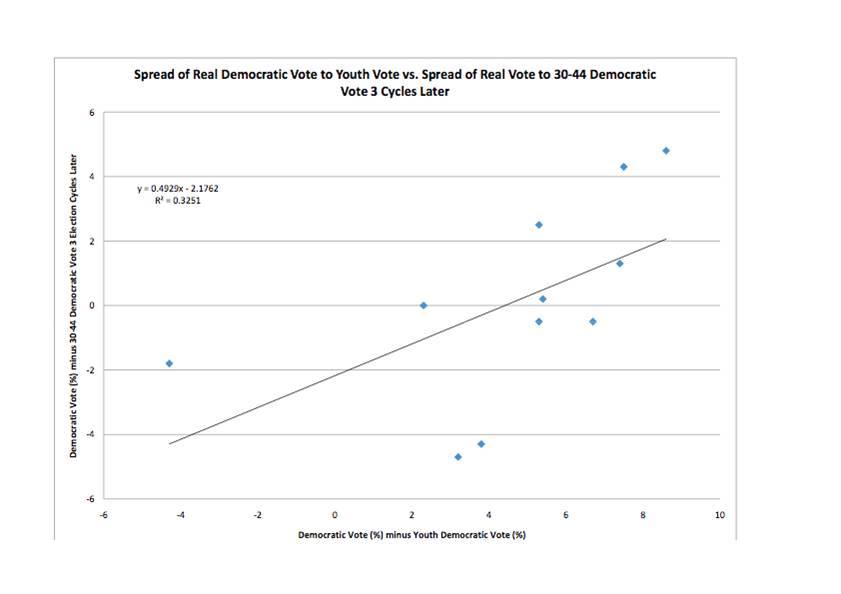

However, Baumann also found evidence that how a cohort first votes does predispose its members to lean in that direction in subsequent elections. That is, some degree of partisanship seems to endure regardless of circumstance, and this appears to affect how voters evaluate current electoral conditions. In Baumann’s words, although “factors existing at the time of the election were far more important in determining an individual’s vote than factors existing at the time of socialization, it became clear that our theoretical hypothesis was correct: the youth vote in a given election offered a viable prediction for how a given group was going to deviate from the overall population over its voting life-cycle, but factors existing at the time of the election were still the most powerful predictors of both an individual’s and a group’s presidential vote.” Here are a couple of graphs showing cohort effects. Essentially, what Baumann does here is to compare the vote of the youth cohort three and seven election cycles later to the overall Democrat share of the popular vote in each of those elections. Does the youth vote, as it ages, show a discernible difference from the overall Democrat vote share in any given election?

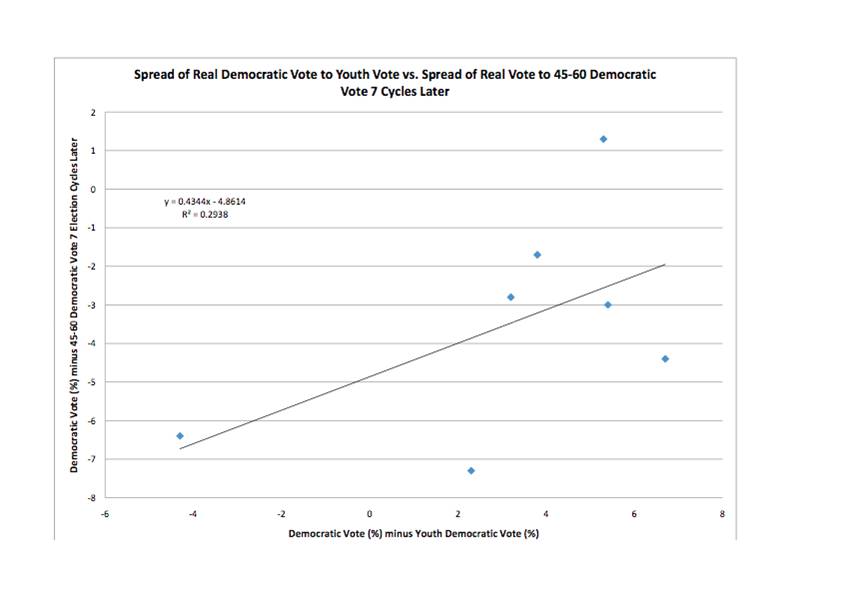

And here’s the figure for comparing the youth vote seven elections later to the overall Democratic vote.

And here’s the figure for comparing the youth vote seven elections later to the overall Democratic vote.

These suggest (with the limits of relying on aggregate data and estimating cohort effects by comparing the cohort to a larger population of which they are a part) that there is a lasting impact of the youth vote. The cohort results are stronger for the election 12 years after the initial youth vote than it is for the election 28 years later. (Indeed, Baumann acknowledges that the seven-election-cycle [i.e., 28-year] results may hinge too much on one data point; take that out and the relationship weakens). Nonetheless, there does seem to be evidence of a small but discernable cohort effect that persists three and to a lesser degree seven election cycles down the road.

These suggest (with the limits of relying on aggregate data and estimating cohort effects by comparing the cohort to a larger population of which they are a part) that there is a lasting impact of the youth vote. The cohort results are stronger for the election 12 years after the initial youth vote than it is for the election 28 years later. (Indeed, Baumann acknowledges that the seven-election-cycle [i.e., 28-year] results may hinge too much on one data point; take that out and the relationship weakens). Nonetheless, there does seem to be evidence of a small but discernable cohort effect that persists three and to a lesser degree seven election cycles down the road.

There are no guarantees, of course. But unless this generation of young voters differs from previous generations, we should expect some type of lasting Obama effect on coming presidential elections. That, not incidentally, provides some ammunition to use against the Clinton-supporters who think the country would have been better off if she had won the 2008 nomination and election. Perhaps so, but she likely would not have inspired as much support among young voters, and thus would have had less of an effect, perhaps, on the future of the Democrat Party.

So, will the current youth cohort still love Obama when he’s 64?

Maybe not. But they should at least demonstrate some affection for the Democrat Party.

That’s some good news for Obama.