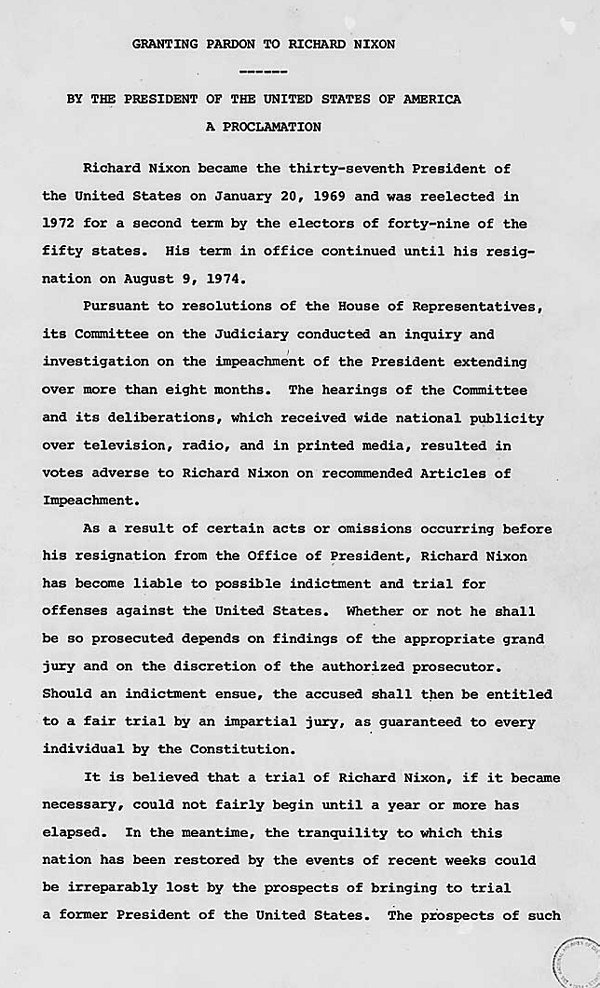

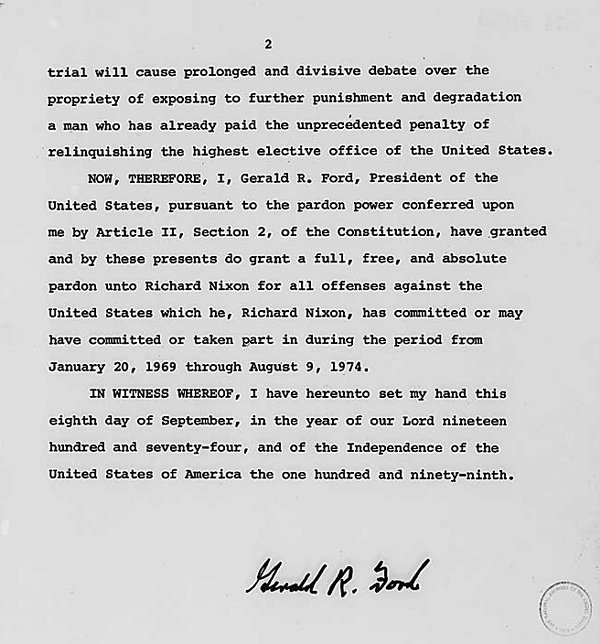

In this week’s trip on the Wayback Machine, we commemorate an anniversary that went largely unnoticed last week in the media focus on Obama’s foreign policy: Gerald Ford’s decision to pardon Richard Nixon. Forty years ago from last Monday, Ford issued the following proclamation granting a “full, free and absolute pardon unto Richard Nixon for all offenses against the United States which he, Richard Nixon, has committed or may have committed” during his time as President:

As Ford noted in his proclamation, he believed developing a case against the former President and bringing him to trial on civil charges would prove to be a prolonged and divisive spectacle that would delay the nation’s ability to heal the wounds inflicted by the Watergate scandal. Ford also thought Nixon, by being forced to resign, had already paid a steep price for his crimes. In his aptly titled memoir A Time To Heal, Ford recalls that he was surprised that the first question at his initial press conference as President “dealt with whether or not I thought Nixon should have immunity from prosecution.” Follow up questions were variations on the same theme. Ford, expressing disappointment that the reporters seemed uninterested in anything else, quickly realized that Nixon’s legal status would be front and center until it was resolved and that adjudicating Nixon’s guilt in a civil trial would likely be a very lengthy process lasting more than a year. “The story,” Ford concluded, “would overshadow everything else. No other issue could compete with the drama of a former president trying to stay out of jail.” And so, after consulting with five of his closest aides, Ford decided to issue the pardon. “The hate had to be drained and the healing begun.” Here is his address explaining the pardon decision:

[youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=eM9dGr8ArR0]Not everyone accepted Ford’s explanation. His press secretary Jerry terHorst resigned in protest, the most visible symbol of a vehement public backlash that Ford confessed he failed to fully anticipate. Most notably, critics suggested there was a secret deal in which Nixon agreed to resign on Ford’s promise to issue the pardon. And, in fact, Nixon aide Alexander Haig had presented Ford with a document describing the pardon power and another blank pardon form. Both later denied that any discussion of a deal took place, but the perception that one occurred damaged Ford’s political standing. His approval rating, as measured in Gallup polls, dropped from 71% before the pardon to 49% after it was granted.

How much of a long-term political price Ford paid for the pardon remains a matter of speculation. In the aftermath of Watergate, and with a poor economy, he was already facing a stiff headwind as he sought reelection in 1976. Early polls showed Ford trailing his opponent, Jimmy Carter, by more than 20%, and Carter was quick to bring up the Nixon pardon during their presidential debates. Polls suggested that the pardon remained an important issue for many voters – but so did an economy plagued by both slow growth and inflation. In the end, although Ford was able to close the gap with Carter (a final Gallup poll actually showed Ford ahead 47%-46%), he lost a very closely contested contest; Carter won 297 electoral votes to Ford’s 240 and took the popular vote by 50%-48%.

In his memoirs, Ford begins his post-election chapter by asking, “What if I hadn’t pardoned Nixon?” – the first, and probably most significant, of several “what ifs” he lists that might have turned the election. However, throughout his post-presidential life he steadfastly refused to express any regret over his decision. And, over time, many who first criticized the decision came to agree with Ford that the pardon was the right thing to do.

In 2001, a bipartisan panel awarded Ford the John F. Kennedy Profile in Courage award for his decision to pardon Nixon. In his acceptance speech Ford noted, “President Kennedy understood that courage is not something to be gauged in a poll or located in a focus group. No advisor can spin it. No historian can backdate it. For, in the age-old contest between popularity and principle, only those willing to lose for their convictions are deserving of posterity’s approval.” When deciding to pardon Nixon, it is clear Ford thought it was the right thing to do for the health of the nation. But, while he understood he would pay a political price, it is not clear to me that he fully grasped the potential impact of pardoning Nixon on his presidential reelection chances. Would Ford have pardoned Nixon if he knew with certainty that it would cost him reelection? When he was sworn in as Nixon’s Vice President, Ford famously remarked, “I am a Ford. Not a Lincoln.” But I am not sure even Lincoln, in a similar situation, could answer that question.

It is fitting, I think, that we give Ford the last word – here is his speech (click here) accepting the Profile in Courage Award and once again defending his decision to pardon Nixon.