President Obama, a huge basketball fan, once again went on ESPN to fill out his NCAA Division I tournament bracket. (He picked Duke, Ohio State, Kansas and Pittsburgh to reach the Final Four, with Kansas beating Ohio for the championship.) Predictably, as we head into an election year, the political opposition took umbrage at Obama’s actions. Potential Republican candidate Newt Gingrich typified the Republican response when he reportedly told the Washington Times: “Obama picking basketball teams may come to rival Jimmy Carter scheduling the tennis courts in the White House as a symbol of failing at big stuff and trivializing the presidency.”

Is Gingrich correct? Will Obama go down in history as the President who dribbled while Japan burned?

Presidents, of course, have always jumped at the opportunity to demonstrate that they can kick back and enjoy sports, just like Joe and Jane Six Pack. Richard Nixon, also a huge sports fan, once spent an entire (well publicized) day picking his all-time baseball team. Bill Clinton was a dyed-in-wool Arkansas basketball fan who attended Razorback NCAA tournament games.

Of course, given recent events in Japan and in the Mideast – and because we are well into the silly season of elections – it was inevitable that Obama’s participation in March Madness this year would draw partisan criticism. It was in part to blunt this that he began his ESPN presentation by urging viewers to contribute to the Japan relief fund.

What I found most interesting about the reaction to Obama’s ESPN, however, is Gingrich’s allusion to Jimmy Carter scheduling the White House tennis courts, particular in light of my last post based on Jim Fallows’ famous 1979 article “The Passionless Presidency”.

In fact, it was Fallows’ article – and Carter’s response to it – that permanently elevated the tennis court story into what has become a lasting metaphor for Carter’s tendency to immerse himself in trivial detail, at the expense of the big picture. In the May (published in April) 1979 Atlantic Monthly article Fallows wrote: “Carter came into office determined to set a rational plan for his time, but soon showed in practice that he was still the detail-man used to running his own warehouse, the perfectionist accustomed to thinking that to do a job right you must do it yourself. He would leave for a weekend at Camp David laden with thick briefing books, would pore over budget tables to check the arithmetic, and, during his first six months in office, would personally review all requests to use the White House tennis court.” Fallows noted that he knew Carter was approving court use because, as a former collegiate tennis player, Fallows would send in personal requests to use the White House courts, and he would receive his answer, via a checked box (yes or no) from President Carter.

As I noted in my previous post, Fallows’ two-part Atlantic Monthly article created a minor news sensation at the time both for the criticisms he raised about his former boss as well as the propriety of a recent employee writing a “kiss and tell” article so soon after stepping down. (Never mind that the article was in many respects actually quite effusive in its praise of Carter – as Hamilton Jordan noted in his draft response to Fallows, the overall fallout from it severely hurt Carter’s public image.)

Interestingly, however, as Fallows notes, he wasn’t the first to raise the tennis court issue with Carter. A few months before, during a one-on-one interview with President Carter on his PBS show, Bill Moyers also addressed the issue:

MR. MOYERS. You were criticized, I know, talking about details, for keeping the log yourself of who could use the White House tennis courts. Are you still doing that?

THE PRESIDENT. No—and never have, by the way.

MR. MOYERS. Was that a false report?

THE PRESIDENT. Yes, it was.

It was inevitable, then, that when Fallows’ article came out in April, 1979, the media would try to resolve the apparent contradiction between Carter’s response to Moyers and Fallows’ claim. They got their chance soon enough, when Carter held a press conference on April 30, 1979 to discuss his energy plan. The exchange went like this:

“Q. Mr. President, how do you respond to the statements by Jim Fallows, who was your chief speechwriter for more than 2 years, on a number of things, but specifically that while you hold specific positions on a number of individual issues, that you have no broad, overall philosophy about where you’d like to see the country go? And on another point, Fallows says that you signed off personally on the use of the White House tennis courts, but you told Bill Moyers that you didn’t. What’s the truth about that?

THE PRESIDENT. Let me say, first of all, that I think Jim Fallows is a fine young man. And he didn’t express these concerns to me while he was employed by us. This is the kind of question that has to be faced by any President when someone leaves the White House. It’s happened many times in the past.

Jim Fallows and I agree on most things. His assessment of my character and performance is one of those things on which we don’t agree— [laughter] —and this is unfortunate, but understandable. He left the White House employment with a very good spirit of friendship between me and him, and with no insinuation that there were things about which he was disappointed.

The White House tennis court: I have never personally monitored who used or did not use the White House tennis court. I have let my secretary, Susan Clough, receive requests from members of the White House staff who wanted to use the tennis court at certain times, so that more than one person would not want to use the same tennis court simultaneously, unless they were either on opposite sides of the net or engaged in a doubles contest.”

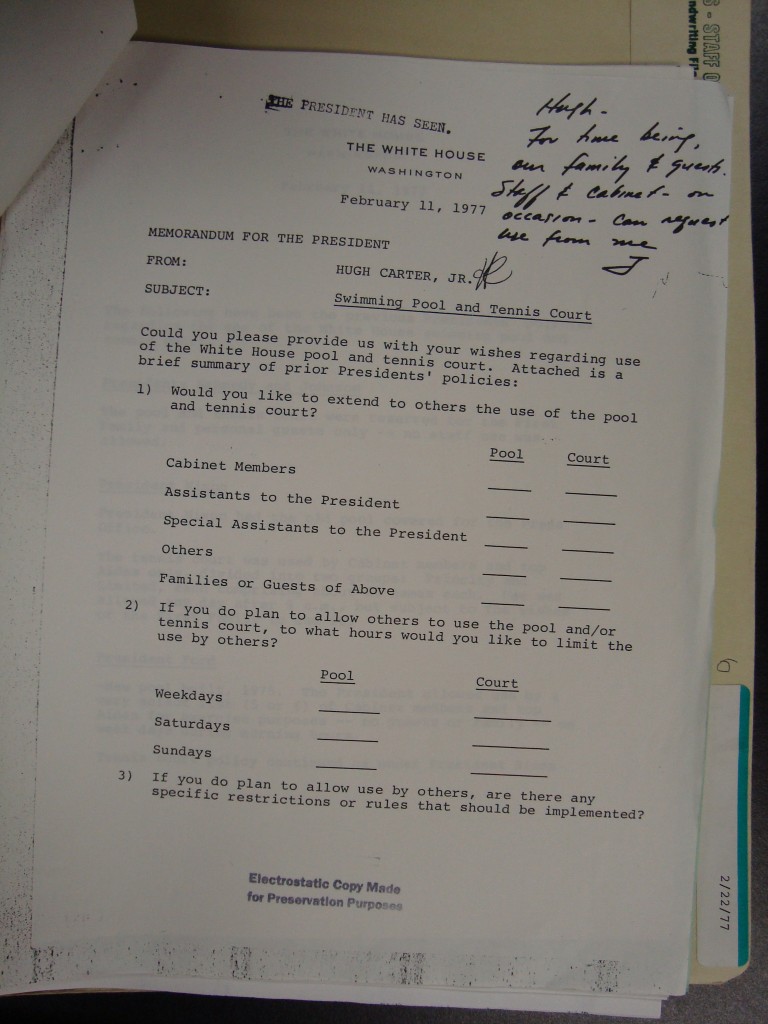

This is media-speak for a “non denial-denial”. Clearly, Carter had walked back from the strong assertion he made to Moyers that the story was simply false, although he still refused to acknowledge that he personally approved who played on the White House tennis courts. Even this revised version, however, was not the complete truth. In fact, as this memo from the Carter Library shows, Carter did instruct his aide (and cousin) Hugh Carter very early on his presidency that use of the White House swimming pool and tennis courts would be restricted to immediate family members, but that “staff and cabinet can – on occasion – request use from me.”

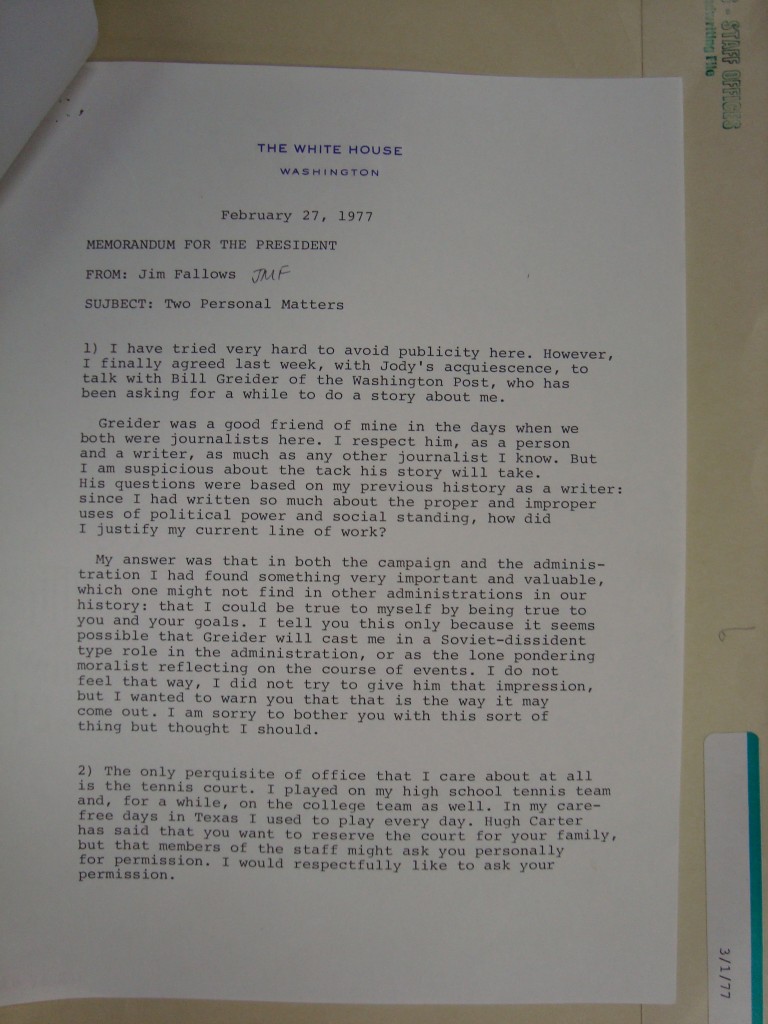

And, as Fallows noted, he was one of the staff members who made those requests – here’s a memo from him to Carter dated February 27, 1977, in which Fallows allows that “The only perquisite of office that I care about at all is the White House tennis court.” He then goes on to make a request to use the court. (I can’t tell from the archival record how Carter responded in this instance, but Fallows indicates in his Atlantic article the he did get permission on some occasions.)

So, is Obama destined to suffer Carter’s fate, with the basketball court substituting for the tennis court? It’s doubtful. The tennis court incident came to symbolize Carter’s presidency because it was an accurate short-hand for his leadership style. He did tend, particularly early in his presidency, to micromanage excessively – it takes but a week in the archives to realize just how detailed-obsessed he could be. (This included, for example, correcting his staff’s grammar on their written memos!)

While partisans may carp about Obama’s foray into the world of March Madness, my guess is that most Americans care more about whether they win their own pool or not than they do about the President taking time out to have some fun. And few Americans will begrudge the President the opportunity to indulge one of his favorite passions. Still, if I was the President, I might delegate responsibility for playing on the White House basketball court to someone else.