Bob Johnson, as is his wont, chastises me once again for implicitly suggesting in my previous post that Americans last Tuesday again voted for divided government. Bob writes, “In fact I suspect that we could and in fact may be getting divided government despite the wish of every voter that the national government be unified — under their party’s leadership, of course.” In one respect Bob is right, of course; as I should have said more directly in my post, most Americans are not voting for divided government. However, that is not the same as saying most Americans who voted on Tuesday preferred to have unified government under Democratic control! (Or Republican control, for that matter.)

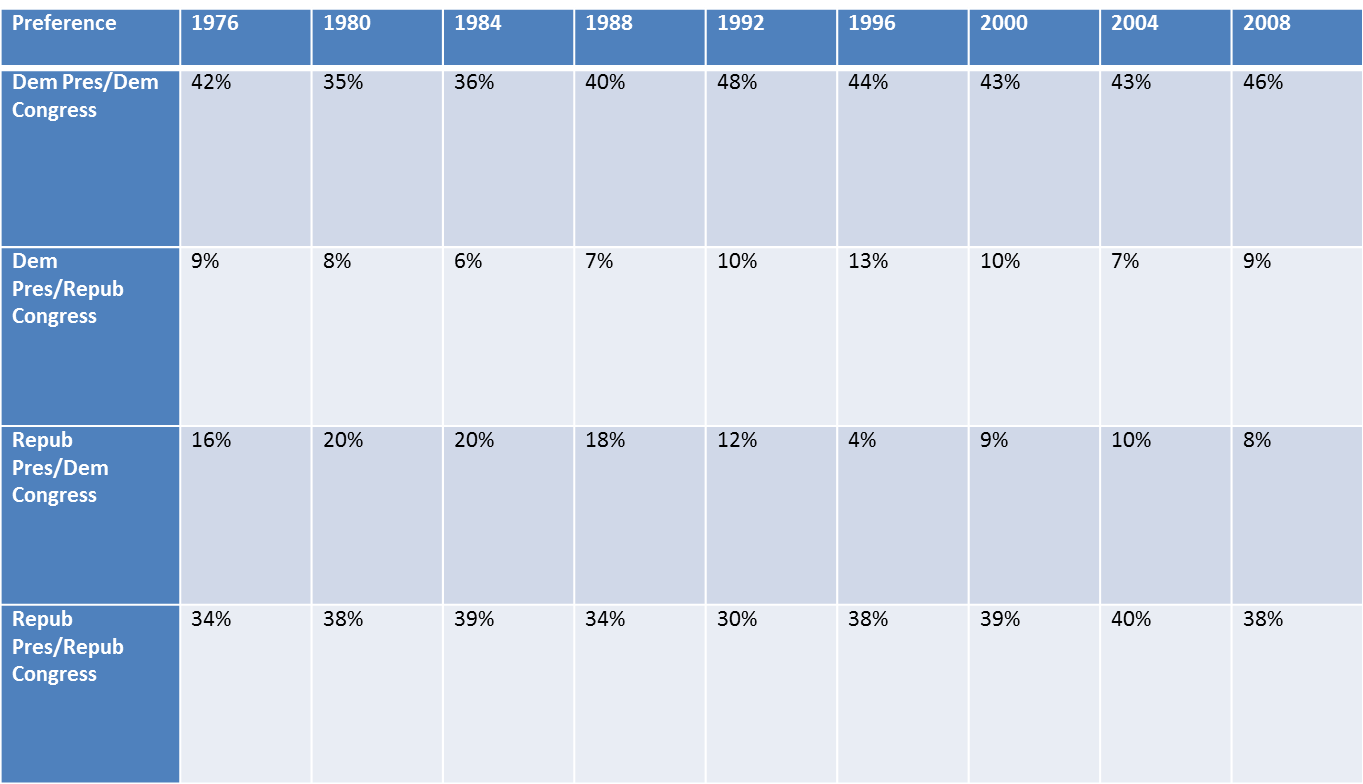

It is true that, in the aggregate, Democrat candidates likely won slightly more popular votes in House races than did Republicans. House votes are still being counted, and we need to be careful about counting votes in districts where incumbents from the same party were pitted against each other. But at this point preliminary numbers suggest that, in the aggregate, Democratic House candidates tallied about 50.3% of the vote to about 49.7% for Republicans, for a margin of about .6% in Democrats’ favor. And, of course, Obama won the popular vote; although the final numbers aren’t in, he’ll likely get close to 51% of the vote. Not surprisingly, Obama supporters cite these numbers to argue that most Americans voted for unified government under Democratic control. But this is probably not the case. Consider the National Election Study data regarding split ticket voting in the nine most recent elections to Congress and the Presidency, as summarized in this table:

As you can see, going back to 1976, not once did a majority of voters, at least based on the NES data, vote for unified government under Democratic or Republican control. Bob is correct, of course, that a strong majority of voters would prefer unified government – if their preferred party was in control. However, there is always a small plurality of voters who, for whatever reason, split their ticket. And that means a majority of voters typically oppose unified control under the opposition party.

Put another way, the 50.4% of voters who voted for Obama last Tuesday are almost surely not the same 50.3% of voters who voted Democratic in the Congressional race. Indeed, on average across the last 9 national elections, about 13% of voters have supported the Democratic presidential candidate while voting Republican at the House level. That percentage has dropped in recent years, as has split-ticket voting more generally, but even if we restrict out analysis to the last four elections, it is still about 8% of voters who split their ticket in this fashion. Another 10% on average across the last four elections have opted for the Republican presidential candidate but supported a Democrat in the House race. So, we see a bit more than 17% of voters splitting their tickets in the last four elections. This is in part a testament, no doubt, to the power of incumbency in House races.

But it is also reminder, apropos Rob Mellen’s comment, that we do not have a parliamentary system, in which our president is selected based on the popular vote for the legislative branch. Instead, ours is a system of separated institutions, each with its own electoral base, sharing powers. As Bob notes, it is that combination of staggered elections and separated electoral constituencies that makes it easier for elections to produce divided government.

But is divided government really all that bad? Bob will undoubtedly be happy to learn that David Mayhew has come out with still another book, Partisan Balance, extolling the virtues of our system of shared powers, despite – because of? – its propensity to return divided government. Mayhew’s essential point is that despite the intense partisan polarization that characterizes government at the national level, the system of staggered elections and different constituencies means the policy process never systematically tilts too much in favor of one party at the expense of the other. This, of course, drives party purists at both ends of the ideological spectrum nuts – far better, they argue, that one party be allowed to control the government, pass their agenda, and be held accountable for the results, than to have to endure a policy process characterized by partisan bickering, fiscal cliffs and incremental change at best.

That might be true. But polls indicate that, although there is variation across time, typically as many Americans support divided government as do prefer unified government, although opinion varies by whether their preferred party controls the presidency or not. Moreover, consistent with the NES data, there’s never been a majority of Americans surveyed who express a preference for unified government; most are either opposed or indifferent.

Yes, we are facing two more years of divided government. That’s nothing new. And it may not be a problem, at least from the perspective of Joe and Jane Sixpack. And, for that reason, I’m guessing Tuesday’s results would please “Little Jemmy” Madison as well, even if modern-day party purists are frustrated once more.