Who won the current round of negotiations regarding whether to extend the Bush tax cuts? That is the question currently being debated by the punditocracy. It is also the wrong question. Indeed, many of the assessments regarding the tax deal negotiated by President Obama and members of Congress earlier this week reveal a fundamental misunderstanding regarding the nature of presidential power as exercised in the legislative process.

At the center of debate is a Senate bill that would extend the so-called Bush tax rates for two years; extend unemployment insurance for 13 months, cut payroll taxes, reinstitute the estate tax at 35% (with a $5 million exemption) and offer several other tax breaks to individual tax payers and businesses. The cumulative cost of this legislative package would be about $858 billion, with about $801 billion of that in the form of tax breaks. This compares, for example, to the approximately $800 billion price tag of last year’s economic stimulus.

Predictably, liberals blasted the President for caving to Republicans and reneging on still another campaign pledge – this time his promise not to renew the tax cuts for those earning more than $250,000, and for accepting a lower estate tax rate and higher exemption level than what Democrats wanted. Much better, they argued, that the President draw a line in the sand and threaten to veto any bill that extended the Bush tax cuts, even if it meant no bill and a tax increase on all taxpayers beginning January 1. Most likely, they argued, a veto threat would force Republicans back to the bargaining table to make more concessions. Conservatives, including a leading Tea Party group, are similarly dismayed, but for the opposite reason: they argue that the bill is still another budget-buster that will increase an already historically high deficit while providing little actual economic stimulus. Taken as a whole, they argue, this legislation is a very good deal for Obama and Democrats.

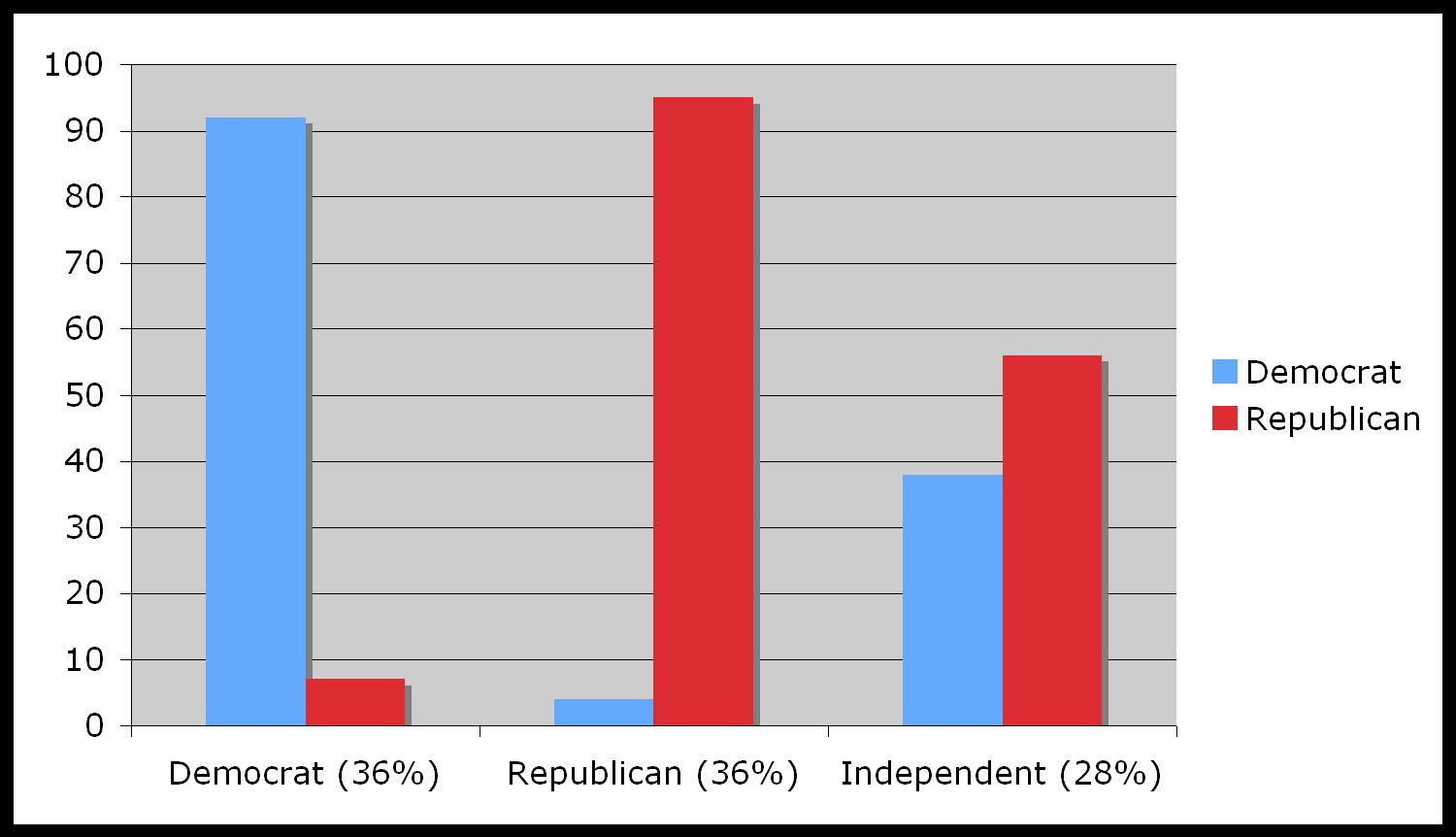

Try telling that to House Democrats; they promptly passed a nonbinding resolution calling on members to reject the Senate bill as currently drafted. In defending the deal during his press conference, Obama reiterated his opposition in principle to extending the Bush tax cuts for those making more than $250,000. But he also took time to criticize both “hostage-taking” Republicans and “sanctimonious” liberals. Party purists on both the ideological Left and the Right reacted by alternately questioning and bristling at Obama’s characterization, but in fact, the President had neither group in mind when he made those statements. Instead, those remarks were targeted at the independents that deserted Obama and the Democrats in droves during the most recent midterm – Obama was telling them that he understood what the midterm results meant. Indeed, it was this electoral calculation – the need to win back those independent voters – which I believe lies at the heart of Obama’s decision to negotiate a deal with Republicans regarding extending the tax breaks. In 2010, Democrats lost independents by roughly 57%-38%, a reversal of their support for Obama in 2008. Obama needs to win back this group if he is to secure a second term. (Here are the exit polls results showing support the midterm vote broken down by Democrats, Republicans and Liberals.)

This electoral calculus is a useful reminder that, contrary to the spin of armchair pundits, negotiations between the President and Congress can rarely be evaluated on the basis of the immediate legislative outcome. Pundits (and some political scientists) too often evaluate these interactions as if they are a one-time, zero-sum game, with clear-cut winners and losers. This is almost never the case. In this instance, Obama and Republicans both made sacrifices to achieve crucial policy objectives, and they did so knowing full well that this was not the end game. All these choices must be evaluated in terms of what happens in 2012, and with the understanding that they will all be revisited shortly thereafter.

Of course pundits on both sides of the ideological aisle are free to urge their political leaders to stand on principle, consequences be damned. They do not have to worry about the consequences if their calculations are wrong, or if no deal is struck. Alas, those at either end of Pennsylvania Avenue do not have this luxury; they understand there will be significant repercussions from a failure to make a deal. The risk of standing on principle is that nothing gets done, taxes go up, and unemployment benefits run out. Moreover, Republicans are going to be in an even stronger bargaining position come January, when the new Congress is sworn in. These deadlines created an incentive to craft a deal – one in which there are no clear winners and losers, but in which everyone gives up something to get something else. And that is almost always the case when it comes to making difficult decisions – Congress does not act until the alternatives of not acting seem more costly.

Did Obama give up too much, too soon? What were the alternatives and what were the risks associated with each? Presidential power, Richard Neustadt famously wrote, is the power to persuade. And persuasion means getting others to do what you want them to do by making them see that it is in their interest to do so. That usually requires bargaining and compromise. Neustadt’s words are frequently cited, but less frequently taken to heart by pundits and even political scientists. Bargaining between the President and Congress is a repeated game played out under conditions of limited information and uncertain outcomes, in which the choices one makes today must be evaluated in part on the impact they have on one’s ability to achieve objectives down the road. No vote is made in isolation, and rarely are there obvious winners and losers. This deal is no exception. House Democrats may be able to tweak some of the details as laid out in the Senate version, such as changing the estate tax rates, but in the end this bill will pass in a form that will make party purists on both sides unhappy and which will have no clear winners or losers. In so doing, it will also remind us once again of the difference between governing and “pundicating” – those in charge must deal with the consequences of their choices (or lack thereof), while pundits can move on to new punditry.