As we begin assessing the results of the 2012 elections, perhaps the most important takeaway is that, once again, the country has voted for divided government. When this newly-elected Congress finishes its term in January, 2015, we will have had divided government during 42 of the last 68 years, dating back to the first-post World War II Congress in 1947. Much of the media focus, understandably, has been on Obama’s narrow victory, but we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that, as of this writing, it appears the Republicans lost a net of about 6 House seats, and therefore they will retain their House majority with something close to 236 of the 435 House seats. The Democrats, meanwhile, defied expectations (at least mine!) and actually gained two seats in the Senate, upping their advantage there (assuming the two independents Angus King and Bernie Sanders vote with them) to 55-45.

What explains Americans love affair with divided government? In part, our explanations may vary depending on what type of divided government we see – right now the Congress is divided. That is the more rare form of divided government, occurring in just 12 years since 1947. In most other years we see a unified Congress facing a president from the other party. It is tempting to think, but harder to prove, that voters are engaged – consciously, or subconsciously – in some type of partisan balancing act. If they are consciously dividing control, the question is why? One explanation that was particularly popular when split control meant choosing a Republican president and Democratically-controlled Congress is that voters saw the parties having different strengths. Republicans were stronger on defense, and hence better suited for the Presidency, while Democrats were more protective of the social safety net and therefore were given control in Congress. However, the partisan roles have been more often reversed in divided government since 1994, with Republicans controlling at least the House and Democrats sitting in the Oval Office. Note that, as Mo Fiorina reminds us, not all voters need to be engaged in this type of reasoning for split government to occur – divided government only requires a minority of voters to split their ticket. Despite this, critics of the balancing argument suggest this still imposes a relatively high threshold of purposive voting on the part of voters.

A second argument explaining divided government focuses not on ideological or partisan balancing, but instead on structural factors. Thus, one explanation for why Democrats retained control of the House for so long, even as the nation elected Republican presidents, is that Democrats, by virtue of more active political participation in state government, simply fielded a more experienced and hence stronger set of candidates at the national level. That is, they benefited by, in effect, having a stronger minor league program. It wasn’t until 1994, after Newt Gingrich had been actively recruiting Republicans to run for office at the local level for a number of years that this structural imbalance was finally overcome. In recent years scholars have cited a second structural factor – one that advantages Republicans. They note that Republican voters are more efficiently distributed across the country, while Democrats are bunched up in large urban areas along the coasts. This more efficient distribution – one accentuated by Republican-controlled gerrymandering in many states after the 2010 census – means Republicans “waste” fewer votes in congressional elections.

Does it matter that government is divided? In particular, does it lead to legislative gridlock? On this question, scholars are also divided. David Mayhew has shown that major legislation generally gets churned out whether government is unified or not. Others argue, however, that under divided government it is more likely that the national government will fail to address pressing problems. That is, our answer may depend on whether we are looking at pure policy productivity or at the saliency of the legislative Congress passes in relation to societal concerns more generally.

The answer may also depend on more than whether government is divided or not. Larry Dodd and Scott Schraufnagel suggest that Congress’ legislative productivity depends also on the level of partisan polarization dividing the two parties. When the two congressional parties are internally very unified, but the ideological distance between them is large, legislative productivity can be hampered even during periods of unified government. This is because our bicameral legislative process, with its supermajoritarian hurdles, makes it easier for a unified opposition party to stymie action. Under the current conditions of quasi-divided (split Congress) government and high polarization, the tendency toward gridlock is even greater.

The bottom line is that, for whatever reason, the voters last Tuesday essentially opted for the status quo. Despite protestations to the contrary, Obama did not receive a mandate – if anything, his position is weaker now than it has ever been. That means from his perspective, the legislative window of opportunity starts small, and will likely close quickly. To be sure, I don’t expect that both parties, in their lameduck version, will be willing to drive the country over the fiscal cliff come the start of the New Year. But the long-term outlook for inter-party cooperation on legislation in the incoming Congress is not promising. Republicans, responding to their own constituent pressures, are likely to be as unified in the new Congress as they were in the last. This does not mean major legislation won’t be passed. Mayhew shows that it can still happen – but only when it addresses the political interests of both parties. Those cases are rare indeed.

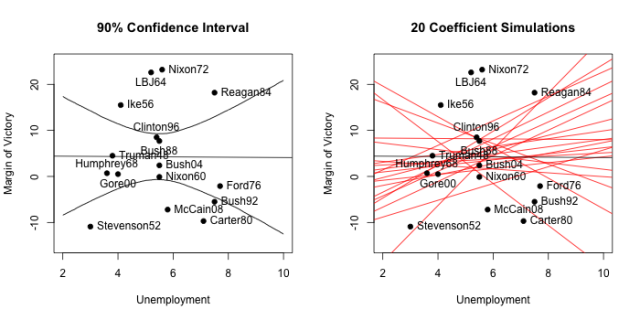

Masket’s conclusion? “The fact is, as the above scatterplot demonstrates, the

Masket’s conclusion? “The fact is, as the above scatterplot demonstrates, the