I want to continue the discussion from my last post regarding media bias and the Obama administration’s decision to take on Fox News. At a minimum, as Jason suggests in his comments on my last post, we expect a news organization to accurately report the news. Jason argues that Fox’s record in this regard is dubious. He may be right – but I have no evidence regarding the relative accuracy of different news outlets beyond the occasional anecdote. Here liberals and conservatives trot out their pet examples (see, for example, Dan Rather, CBS and the Bush-National Guard story vs. Fox News and Obama’s support for “death panels”.) Nor is Jason the only one to critique Fox News – Jacob Weisberg at Slate is among many who argue that there exists persuasive evidence that Fox is not a legitimate news organization (see here.) Evidently, the Obama administration has calculated that by building on these sentiments, they have more to gain than they have to lose in publicly taking on Fox News. I think this is a mistake, in large part because the strategy risks distracting from the coverage of their major policy initiatives. The more coverage devoted to the Fox news controversy, the less time spent on the details of health care. In this respect they are stepping on their own story. More problematic, however, I think they risk alienating the moderate middle of this country, particularly independents that worry less about partisan point scoring and more about whether the Obama administration has effectively addressed their concerns.

To see why Obama may be making a mistake, and to more systematically address the question of media bias, consider the following study, published in 2005, of news coverage by the major U.S. news organizations, including Fox News (actually, Brit Hume’s old Fox news show). This study, by Tim Groseclose and Jeff Milyo is one of the few (maybe the only) efforts of which I know that tries to measure media bias in a more systematic fashion. (I urge you to read the original article here.) Essentially, what they do is create a measure of media bias for several major media outlets, including Fox, across a 10-year period. (More accurately, they select an observation period for each media outlet that yields 300 observations – enough to draw valid conclusions.) They do so by counting the times that a particular media outlet relies on particular think tanks (for example, Brookings, or the Heritage Foundation) or policy groups (such as the ACLU or the NRA) as a source for their story, and then they compare that to the number of times that members of Congress cite those same sources in their public comments. Since we have reasonable measures for the ideologies of members of Congress, we can use this data to place the news outlets that cite these think tanks and other sources on an ideological spectrum. For example, we would expect the liberal Ted Kennedy to rely more on research from the left-leaning Brookings Institution than on studies from the conservative Heritage Foundation. If the New York Times, in its stories, also relies on Brookings more than Heritage to the same degree as Kennedy, Groseclose and Milyo code the Times as having a similar bias as Kennedy. The underlying logic of this measure rests on the idea that journalists rely on their sources to write their stories, and if those sources tend to represent one side of the ideological divide, then their stories will tend to reflect that bias. The authors assume that the public, ideologically speaking, is located somewhere at the middle of the Congressional spectrum.

Using this methodology, what do Groseclose and Milyo find? On the whole, they show that the major news outlets in the United States do show a consistent liberal bias. In their words,

“Our results show a strong liberal bias: all of the news outlets we examine, except Fox News’ Special Report and the Washington Times, received scores to the left of the average member of Congress. Consistent with claims made by conservative critics, CBS Evening News and the New York Times received scores far to the left of center. The most centrist media outlets were PBS NewsHour, CNN’s Newsnight, and ABC’s Good Morning America; among print outlets, USA Today was closest to the center. All of our findings refer strictly to news content; that is, we exclude editorials, letters, and the like.”

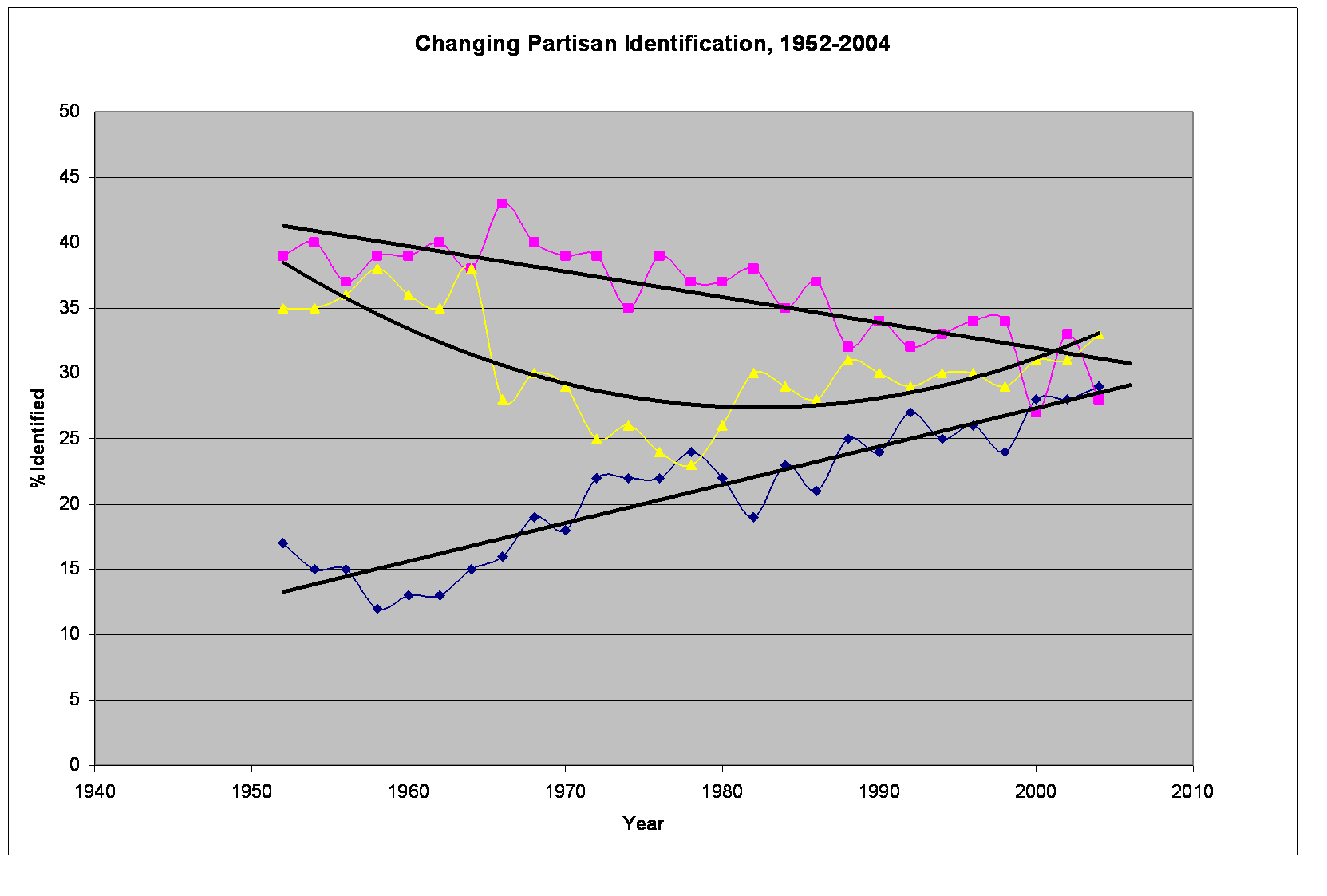

The following table, taken from Groseclose’s website, provides a graphical representation of their findings. (Note that the Wall St. Journal rankings refer to their regular coverage of the news – not their editorials!). The higher the ranking on the table, the more liberal the views/coverage. The “average” U.S. voter is placed at about 50 on the ADA scale, located on the left of the table. It runs from zero (most conservative) to 100 (most liberal).

The table suggests that Fox News (more specifically, the Fox News Special Report with Brit Hume) is more conservative than the other major news outlets – but it is also closer to the “average” American voter/member of Congress than are most of those other news outlets. In short, there is evidence to support both liberals’ claims that Fox is out of step with the mainstream media, and Fox defenders who argue it provides news coverage that is more in synch with the views of most Americans.

The study is not without critics (see, for example, here and here). But it is one of the few efforts made to develop a measure for bias that is replicable by other political scientists, and which goes beyond the commonly cited anecdotal evidence that so often characterizes the often heated debate regarding media coverage. As such, it’s a welcome step forward in trying to put this debate on more systematic footing.

I should add that it is consistent with Bert Johnson’s comments at the end of my last post. Bert took my structural bias argument a step further to suggest that the major news outlets give their audiences what they want to hear – the key word being “audience.” In an era of dwindling audiences, news organizations are struggling to maintain readers (or viewers), and to do so they are increasingly trying to differentiate their product in a way that distinguishes their news coverage from that of their competitors. That means pitching their content toward the attentive audience, rather than simply the “average” U.S. voter. As Bert notes, the attentive audience typically has more ideologically extreme views than that of Mr. and Ms. Sixpack from Palooka, USA. It follows, then, that in an increasingly segmented news industry, cable outlets and other news sources will abandon any pretense of ideological “neutrality” in a rush to stake out an unocccupied spot on the ideological spectrum of attentive viewers. The Groseclose/Milyo study suggests this is precisely what is happening; news outlets are differentiating themselves by catering to the more opinionated and attentive portion of the news audience. They do so for structural reasons related to market share and profits, and not because they are in the hip pocket of the Democratic (or Republican) party.

The danger, of course, is in their rush to stake out a position along the ideological extremes, the news media may exacerbate the polarization of political discourse in this country. Even worse, they may ignore the interests of the moderate middle spectrum of Americans who care very little about the purity of partisan politics, and instead simply want a government that works well, regardless of ideology.