When it comes to writing about polarization in American, who can blame journalists for expressing confusion? The Washington Post’s Dan Balz is the latest reporter to grapple with conflicting evidence and, perhaps more importantly, conflicting interpretation of the evidence by political scientists. In this recent article Balz discusses the results of a new study conducted by the Program for Consultation at the University of Maryland that shows there is little difference in the policy views of citizens in “red” and “blue” congressional districts. (Their findings mirror those of Fiorina, Abrams and Pope in their Culture Wars?) In the same article, however, Balz also quotes political scientist Alan Abramowitz’s take on other data that Abramowitz suggests shows Americans are in fact deeply polarized.

But it is not just the conflicting interpretation of data that journalists must deal with – it is also the loose use of the term polarization itself that contributes to the problem. In common usage, polarization refers to the divergence of political attitudes toward ideological extremes, or a sharp division of a population or group into opposing factions. Understandably, when stories proclaim that Americans’ political views are increasingly polarized, most readers believe this means Americans must be dividing into two camps based on increasingly divergent political views. So, we must be seeing an increase in conservatives and in liberals, and a decrease in those holding more centrist views. (And, in fact, this seems to be what Professor Abramowitz, among others, believes is happening.)

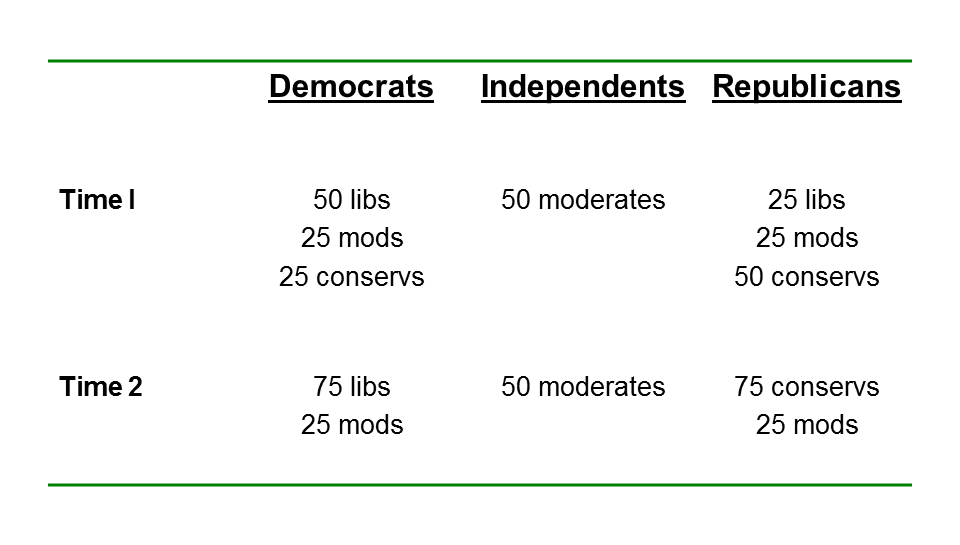

However, as I have discussed in several posts, most of the evidence used to support this claim does not show a process of polarization, as commonly understood. Instead, it shows a process of party sorting. To understand the difference, consider these two graphs taken from a recent paper by Sam Abrams and Mo Fiorina that discusses polarization and sorting. This first graph illustrates what most people think of when they hear the term political polarization. It shows the elimination from Time 1 to Time 2 in the number of moderates, as well as non-liberals in the Democratic Party and non-conservatives in the Republican Party. The end result is an increase in the number of liberals and conservatives, and the disappearance of moderates, consistent with what many people understand polarization to mean.

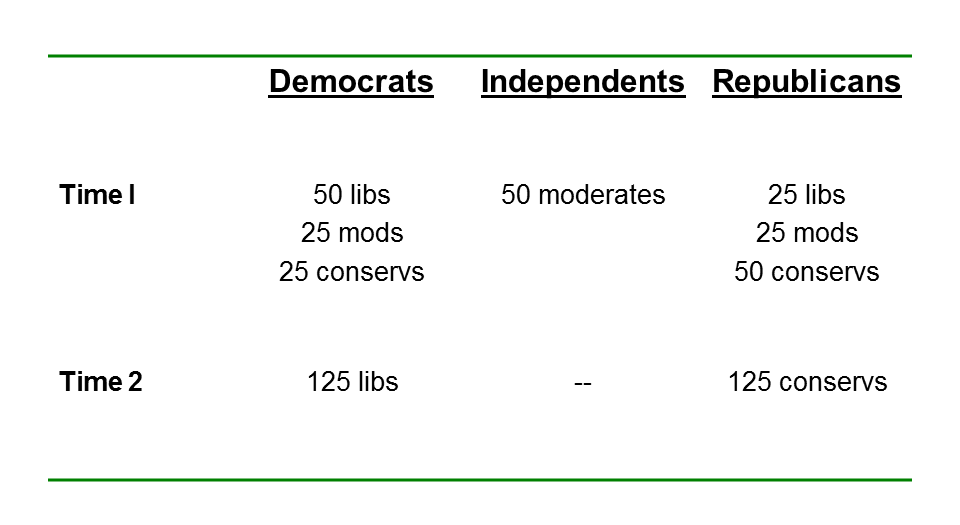

Now, consider graph 2. Here the total number of moderates does not change from Time 1 to Time 2, but both parties purge themselves (through conversion and migration) of most of those who are out of step with the party’s dominant ideology (although some moderate leaners remain in each party). However, there is no increase in the total number of liberals or conservatives – indeed, in the aggregate, the distribution of political ideology hasn’t changed at all. All that has occurred is a better sorting of party affiliation with ideology, so that the Democratic Party has become more uniformly liberal and the Republican more uniformly conservative.

Now, consider graph 2. Here the total number of moderates does not change from Time 1 to Time 2, but both parties purge themselves (through conversion and migration) of most of those who are out of step with the party’s dominant ideology (although some moderate leaners remain in each party). However, there is no increase in the total number of liberals or conservatives – indeed, in the aggregate, the distribution of political ideology hasn’t changed at all. All that has occurred is a better sorting of party affiliation with ideology, so that the Democratic Party has become more uniformly liberal and the Republican more uniformly conservative.

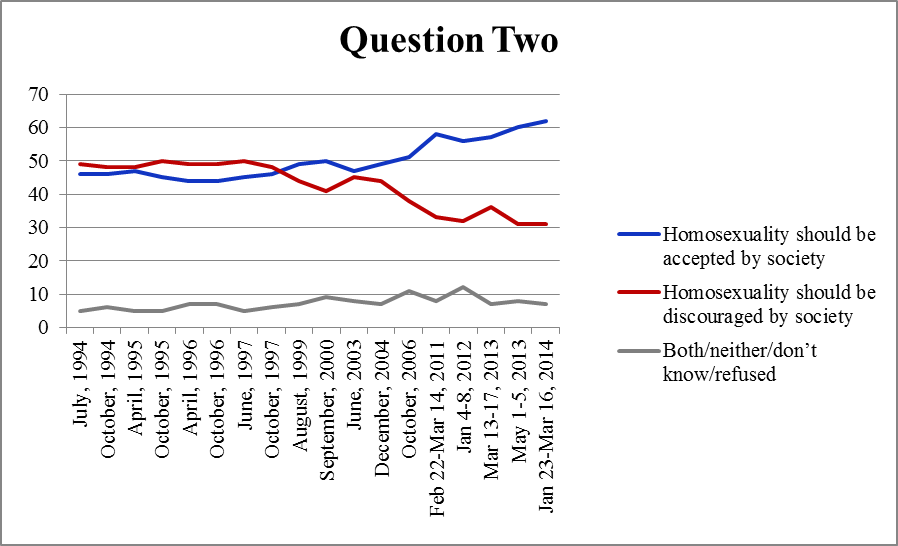

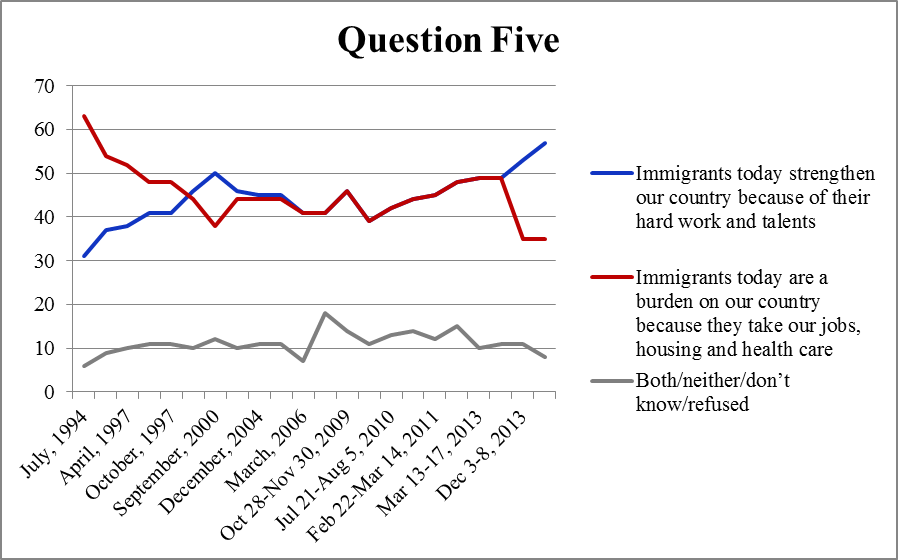

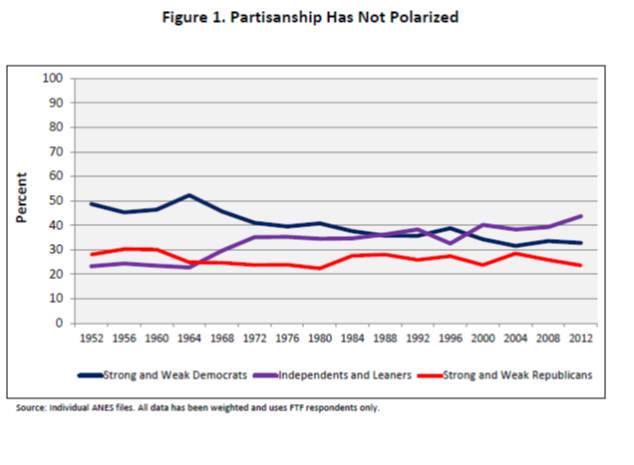

Which is more consistent with what has actually happened in the United States? You decide. Here is a chart, again from Abrams and Fiorina, showing the change in the distribution of partisan affiliation, based on American National Election Studies surveys, since 1952. As you can see, if there is any long-term movement, it is in the slight increase in the number of self-described independents and those leaning independent.

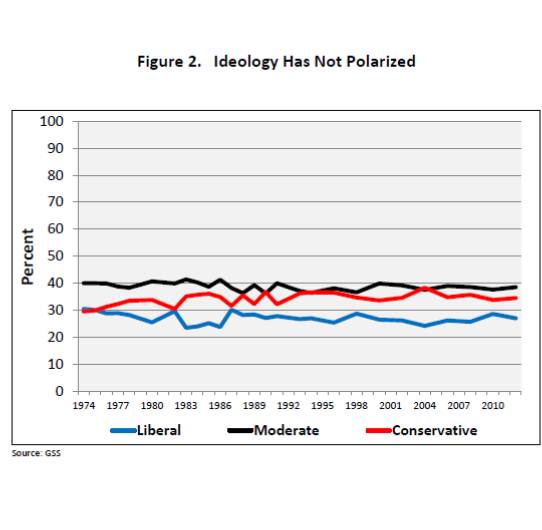

How about changes in ideology over time? Again, as the following chart shows, we see very little movement in those calling themselves liberals, moderates and conservatives.

How about changes in ideology over time? Again, as the following chart shows, we see very little movement in those calling themselves liberals, moderates and conservatives.

Both sets of data, then, are consistent with what Fiorina (and others) have described as party sorting, rather than political polarization. Nonetheless, some colleagues in the profession suggest that party sorting is itself simply another version of polarization. The argument is that even if the parties, or the number of liberals and conservatives, have not grown larger at the expense of the moderate middle, the center of ideological gravity in each party has certainly shifted toward the extremes. So we have seen a process of partisan polarization, albeit not the kind that comports with what many laypeople understand polarization to mean.

Both sets of data, then, are consistent with what Fiorina (and others) have described as party sorting, rather than political polarization. Nonetheless, some colleagues in the profession suggest that party sorting is itself simply another version of polarization. The argument is that even if the parties, or the number of liberals and conservatives, have not grown larger at the expense of the moderate middle, the center of ideological gravity in each party has certainly shifted toward the extremes. So we have seen a process of partisan polarization, albeit not the kind that comports with what many laypeople understand polarization to mean.

I am uncomfortable with this broader use of the term polarization for several reasons. First, most laypeople, including journalists, don’t always appreciate the differences in the two processes – when they see the phrase polarization, they assume it means a general movement within the public toward the ideological extremes at the expense of the center. (It doesn’t help that stories often drop the adjective partisan when describing polarization.) It bears repeating that there has been no real growth in the number of Democrats or Republicans, which some might argue should be happening based on the term partisan polarization. Second, encompassing different processes under the single term robs polarization of some of its analytical bite. If the processes are different, we ought to acknowledge that by using different terminology. It is confusing enough for journalists and laypeople to hear social scientists give different interpretations based on the same set of data. We shouldn’t further muddy the waters by using the same term to describe very different processes. (Otherwise we should expect more stories with the headlines similar to “We’re Not That Polarized. Oh Yes, We Are”.) If journalists are going to rely on social scientists for guidance on these issues, we need to strive for clarity and precision in terminology. Finally, the implications of a growth in party sorting are much different than those emanating from increased political polarization. To use one example, if the public is more polarized, then it becomes harder to blame Congress for partisan gridlock, since they are simply mirroring broader divisions within their constituencies. But if the views of red state and blue state denizens are not so divergent on major issues, as the survey Balz cites suggests, then we must look elsewhere to place the blame.

In my view, polarization and sorting are two different processes, and we ought to recognize this. We can start by retitling Balz’s story: “We’re Not That Polarized. But We Are Better Sorted. And the Distinction Matters.”