Thirty five years ago this evening, President Jimmy Carter went on nationwide television to give his infamous “malaise” speech. You can watch the speech in its entirety here.

[youtube.com/watch?v=KCOd-qWZB_g]If you listen carefully, you’ll notice that he never actually uses the word “malaise”. Instead, he talks about the “crisis of confidence” that threatened the nation’s “will” and “unity”. It is an emotionally searing speech, noteworthy for the candor and level of introspection Carter displayed to a national audience that has rarely, if ever, been expressed by any elected official again. Unfortunately, through the years, the “malaise” speech has come to symbolize all that went wrong with the Carter presidency. As a result, pundits – and presidents too – have tended to draw the wrong lesson from this event.

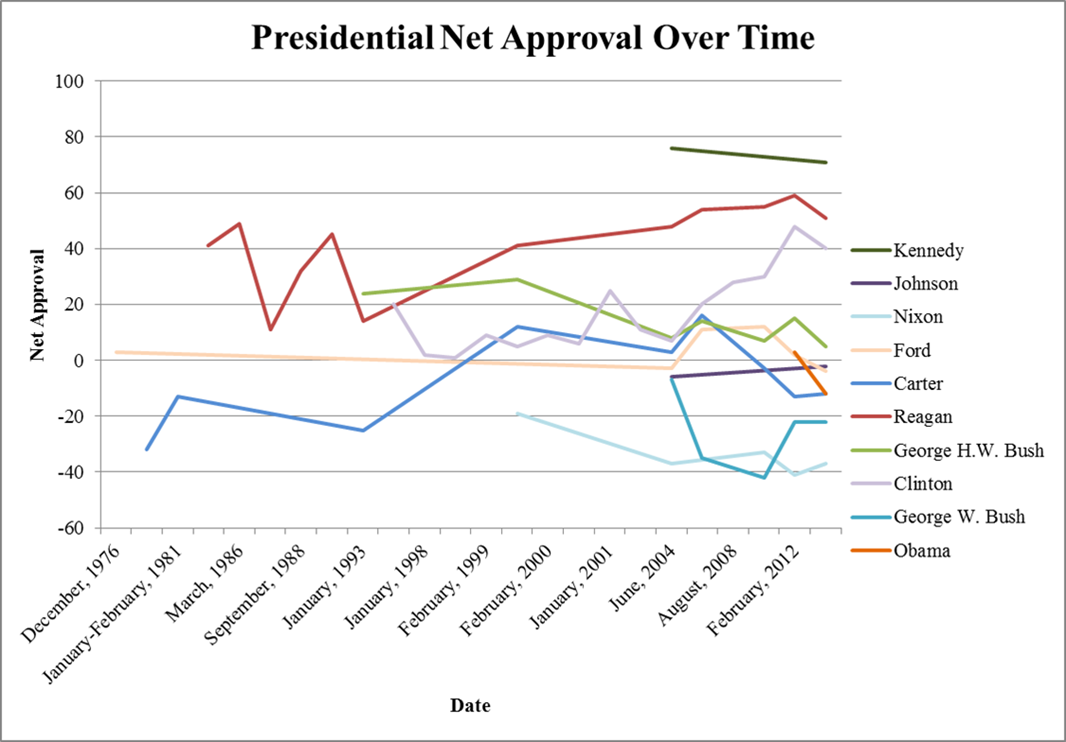

Some context is useful in understanding why Carter gave the speech. Three years into his presidency Carter’s approval ratings had dropped below 30% and were at the low point of his presidency to date. While he was preoccupied with two important overseas trips – one to sign the SALT II treaty with the Soviet Union and then a diplomatic visit to Japan and South Korea – Americans back home were waiting in long gas lines as they suffered through another energy crisis triggered in part by the Iranian revolution that overthrew the American-backed Shah. Initially Carter planned on giving still another speech urging Congress to address the energy crisis, but ultimately he decided that it would be waste of his time, since he had already given several talks on this topic. Instead, he retreated to Camp David, and summoned leading public figures, including many prominent religious leaders, to meet with him to discuss the state of the nation. Then, like Moses coming down the mountain, Carter went on television to give his famous address, one that went well beyond discussing the energy crisis, although he discussed that too. But most of the speech showcased Carter, the former Baptist preacher, as the nation’s “minister-in-chief”, beginning with his self-flagellation as he recounted criticism of his leadership, and then addressing what he believed to be a growing loss of confidence in the nation’s leaders and institutions.

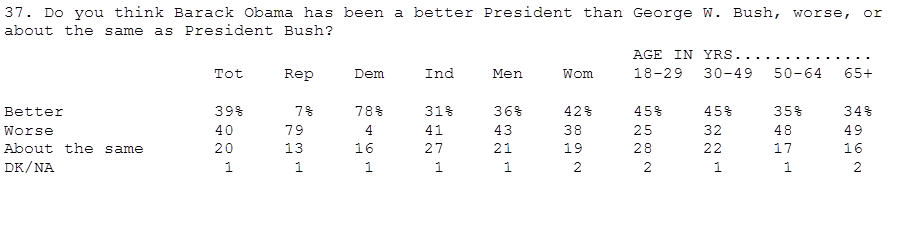

As you might expect, the speech generated a mixed reaction. In part this was because Carter undercut the message of unity by which he ended the speech when three days later he asked for the resignations of his entire cabinet and key White House advisers (he accepted three cabinet resignations). Gallup polling data that I can find suggests a modest boost, from 29% to 32% in his already tepid approval ratings, although the polls are taken so far apart (the first on July 10 and the next on July 30) that it’s hard to know how much movement to attribute to the speech and subsequent firings. (Reportedly, internal White House polling showed a much bigger overnight boost in approval, but this was before the cabinet firings.)

The long-term impact of the speech, however, may have been more significant. Like the ebullient FDR running against the dour Hoover during the depths of the recession in 1932, Ronald Reagan, with his sunny optimism, was immensely successful during the 1980 campaign at portraying Carter as the nation’s “scolder-in-chief” who was too willing to blame Americans rather than his own inept leadership for the nation’s ills. Although polling suggested that many Americans’ views on the issues were closer to Carter’s than to Reagan’s, it did not prevent Reagan from winning the election. When Reagan won reelection in a landslide four years later by campaigning on the “It’s morning again in America” theme, the die was cast. But it wasn’t just Reagan who capitalized on Carter’s failed attempt to level with the public – Ted Kennedy later noted that the speech convinced him to challenge the incumbent president for the Democratic nomination.

Mindful of the purported lesson of Carter’s “malaise” speech, no national candidate would ever again make the mistake of speaking so candidly, and in such critical tones, about the American people even if much of that criticism was self-directed and perhaps even true. Instead, candidates on the hustings are much more likely to take a page from the Reagan playbook by emphasizing the indomitable American spirit, can-do work ethic, etc. And woe to any candidate who slips up and leaves himself open to the charge that Americans might be at fault for anything, as in this Romney reaction to an Obama statement. That is the lasting legacy of the “malaise” speech.

Meanwhile, Carter went on to have a much more successful post-presidency – indeed, he has arguably been one of the most effective ex-presidents in history due to his philanthropic efforts through the aegis of the Carter Center. He has never expressed any regret to my knowledge regarding the “malaise” speech – indeed, the only regret I have ever heard from him regarding his presidency was his failure to include one more helicopter in the ill-fated Iran rescue mission. But that is a topic for another day. For now, let’s remember when it was morning, again, in America.

[youtube.com/watch?v=EU-IBF8nwSY]