My colleague Bert Johnson specializes in, among other issues, campaign finance and elections, and he has graciously agreed to weigh in on the recent Supreme Court decision allowing corporations to independently spend money in political campaigns. As many of you know, media editorial boards and political pundits have reacted to the Court’s decision with howls of protest, essentially arguing that corporations will now be able to “buy” candidates and determine the outcome of any election that interests them. Rather than a democracy, we’ll be ruled by a plutocracy.

The probable outcome, as Bert suggests here, is not quite as dramatic:

“Three days have now passed since the Supreme Court issued its ruling in the case of Citizens United v. FEC. The Court’s ruling – that corporations and unions must be allowed to engage in independent expenditures in political campaigns – has generated a lot of hyperbole among commentators and activists. The decision’s implications are in fact more modest than most people are claiming, for reasons I’ll discuss below.

Will the Aggregate Amount Spent on Politics Change?

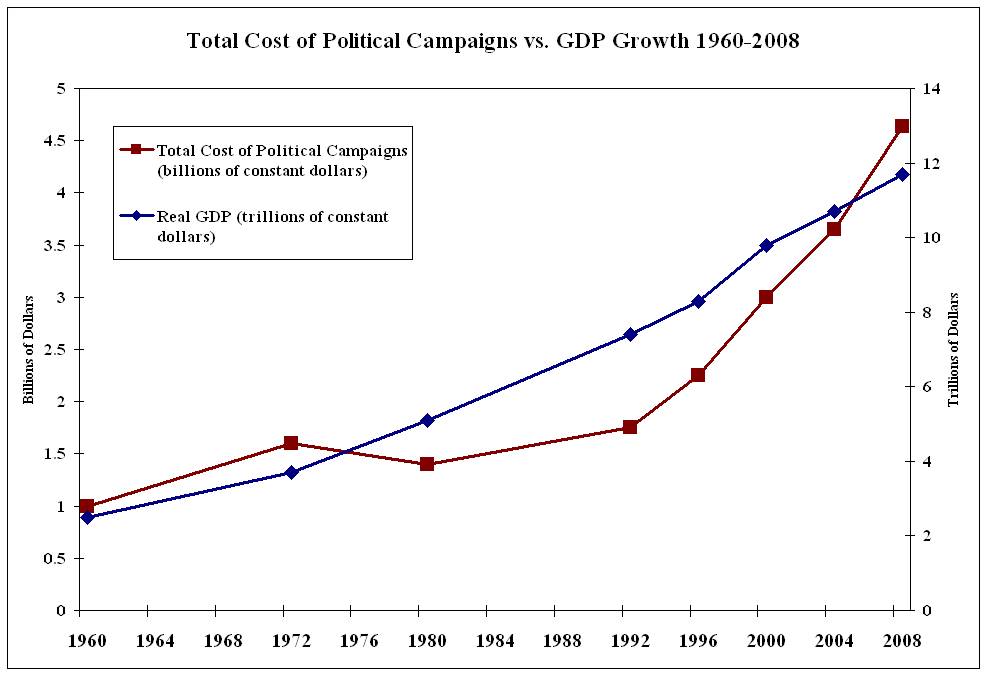

The historical record suggests that the ruling may shift spending around somewhat, so we may in fact see more independent expenditures relative to other types of expenditures, but the overall amount of political spending is unlikely to change much. No regulatory scheme (at least in the U.S. or comparable countries like the U.K.) has made much of a difference in the aggregate level of money spent on political activity. Money spent on politics is very closely related to a country’s gross domestic product, as you can see from the figure below.

The relationship between GDP and political spending is one of the most consistent and longest-standing political science findings, and was first identified by Louise Overacker in the 1930s. An intuitive way to see this is to note that the McCain-Feingold bill banned so-called “soft money” after 2002. This major regulatory change might have been expected to have a clear effect on political fundraising. Soft money funds made up over $250 million in party spending in 2000 and $245 million in 2002, according to FEC figures. After 2002, though, fundraising trends continued along their previous path.

Political scientists Stephen Ansolabehere and James Snyder have found that this relationship holds true in highly regulated environments such as the U.K., as well as in virtually unregulated environments, like California state politics.

Will Corporations Rush to Enter the Political “Marketplace”?

Even if the aggregate total of money spent on politics remains the same, will we see a rush by previously-uninvolved corporations into the political arena? This, too, is unlikely. Under the pre-Citizens United regulatory framework, corporations have had ample opportunity to enter politics, but surprisingly few have done so aggressively. The most natural way of entering the political arena is to form a Political Action Committee (PAC), but fully 40 percent of Fortune 500 companies have no PAC at all (this figure comes from Ansolabehere & Snyder’s research). The average corporate PAC contribution is far below the maximum allowed: in 2006, for example, the FEC reports that the mean corporate PAC contribution was $1,473 (the median was $1,000), even though the law allows a maximum of $5,000 per candidate per election. This relatively low level of investment in political activity under the old rules will likely continue under the new rules.

Will Voters be Deluged with Corporate Ads that Will Affect Election Outcomes?

It’s likely we’ll see more independent expenditures under the new regulatory framework, relative to other kinds of political activity. But the relatively low level of political spending by most corporations suggests that firms will not all leap to involve themselves in independent expenditure campaigns. In 2008, for example, the highest spending corporate PAC was “United Parcel Service, Inc. PAC”, which spent about $4.7 million. This is about 1/5 of one percent of that year’s UPS corporate profits of $3 billion (data come from the FEC and from corporate financial reports). Spending in political campaigns just isn’t very important to UPS (and to other corporations that spend less).

But, say corporations and outside groups *do* start spending a lot in elections. Will they be able to control the outcomes of congressional and presidential races? I’m skeptical. As Matt has drilled into all of our heads, elections primarily hinge on the fundamentals: the state of the economy, presidential approval, and so forth. There’s not a lot of evidence that campaign ads, for example, make a huge difference. Experimental research on media effects suggests that ads can teach people new information, can affect people’s level of enthusiasm, and might play some role in affecting the agenda. They don’t typically change people’s minds. The “swift boat” ads didn’t have a huge effect on the outcome of the 2004 race (contrary to the conventional wisdom), nor did McCain’s “Celebrity” ads in 2008.

OK, Even if the Effect is Small, What’s the Harm in Pushing for A Corporate Independent Expenditure Ban?

Since the Supreme Court’s decision Thursday, reformers have pushed for Congressional action to overturn the ruling. Would this be a good idea? One response might be to argue against it on constitutional grounds, claiming, as the American Civil Liberties Union puts it, that a ban on corporate ads represents a “poorly conceived effort to restrict political speech.”

But as a political scientist rather than a constitutional scholar, I’d prefer to focus on the practical consequences. Reformers interested in improving our system of representation could choose a more productive way to go. The real problem with representation in our system is a lack of competitive races. Robust competition increases voter knowledge, voter interest, and electoral participation, yet House members have a 90 percent-plus reelection rate and only a few dozen races are truly contested each cycle. Limiting expenditures does little to improve competitiveness, and is often counter-productive. Encouraging competitiveness is usually a matter of more spending, not less – but the spending has to be on the challenger side. Incumbents can spend whatever amount of money they want, but it is challenger spending that is the better predictor of competition and of incumbent defeat. (As Gary Jacobson first pointed out in the 1970s, the highest spending incumbents are often the ones who lose, since high spending levels indicates that they’re in trouble.)

The Citizens United ruling does little to either increase or decrease the amount of resources available to challengers. A better way to go might be to reduce restrictions on the entities that have an incentive to increase the competitiveness of campaigns: the political parties. As RNC Chairman Michael Steele said in a statement the other day, this would help to improve competition and to “encourage a vibrant debate on the issues.”

Bert – I agree that the actual impact on elections from the CU case won’t be huge, but the signal feels horrid, asserting corporate rights at a time that most Americans feel victimized by the business world.

Personally, I think the proper solution is full public financing of elections to ensure that challengers need not be personally monied or supported by wealthy benefactors, and to try to create a level playing field. As a media scholar, I focus on the fact that broadcasters get free licenses to the airwaves while raking in political ad dollars (the political ad sector is second only to automobiles, which is astounding when considering how seasonal politics are). If broadcasters were required to provide free access to the airwaves for candidates as a condition of their license, I think much of the corruption of our political system would be lessened.

I guess I’d be in favor of free airtime, as long it was done more effectively than it was in the 1996 presidential campaign. I’d support public financing too, as long as there were no spending limits attached.

Bert, do you think that expensive television advertising will become less meaningful with the rise of internet video (youtube et al) that is free to post political advertisements on?

Hi Alex! Jason might have a more informed opinion of that than I do, but the one thing I can say is that the amount of money that candidates spend on TV does not appear to have diminished as a percentage of their overall budgets. I’m sure it’s tougher to reach the average viewer on TV than it used to be, but that might just mean candidates will run ads more frequently.

Alex – the cost of TV advertising has actually been rising, despite ratings declines, and because of the spread of audiences across channels & platforms, it’s harder to reach a critical mass, requiring more ads to be purchased (like Bert said). As for the question of YouTube, it’s definitely a useful and cheaper tool, but what I’ve read suggests that viral ads & videos don’t really reach the undecideds as much as the core supporters. But it’s still too soon to see real trends in the impact of online video, I think.