Stop me if you’ve heard this before.

Media pundit Howard Fineman begins his Huffpost Politics column today by asking, “Why is America on the edge of a political and fiscal nervous breakdown?” He goes on to answer his own question by providing, as the essay title neatly summarizes, “15 Reasons Why American Politics Has Become An Apocalyptic Mess”. With the exception of gerrymandering, I think a plausible case can be made that at least 13 of the 15 reasons Fineman cites contribute, at least in part (in some cases a very small part), to the current polarized political climate in Washington. DC. (Despite persistent media claims to the contrary, political scientists don’t find much evidence that gerrymandering contributes to partisan polarization.) To be sure, Fineman’s essay would be more useful if he provided some relative ranking of the various reasons in terms of their impact on polarization, but on the whole I don’t think he does serious injustice to the topic.

Except for Reason 5. Under the heading “Two Cultures” Fineman writes: “Americans used to inhabit a world of shared social mores, even if millions of people were coerced into accepting them. Now voters now live in two barely overlapping moral worlds: Secular Metropolitan America and Biblical Traditional America. Americans can spend most of their waking hours enveloped in one journalistic gestalt or another, staring at one cable show/website version of reality or the other. It makes political differences harder to bridge.”

Fineman is not the first to make this assertion, of course; the claim that we are a deeply polarized along cultural and moral lines dates back at least to 1992, when Pat Buchanan used his address during the Republican presidential convention to warn of an ongoing religious and cultural war for the “soul of America”. In the aftermath of the 2004 election, political wags divided the U.S into a Republican-oriented “Jesusland” and a Democratic-leaning “United States of Canada”. And, as my last post notes, journalists continue to trumpet the theme of a deeply polarized America today, most noticeably during reporting about the government shutdown. Fineman is but the latest, but undoubtedly not the last, media pundit to make this claim.

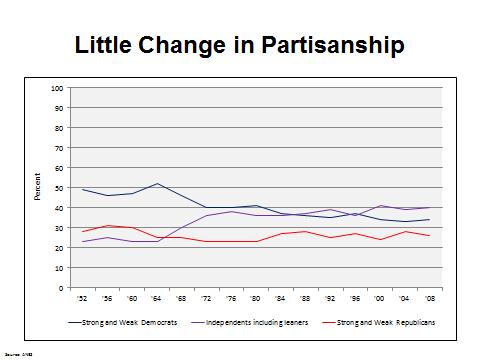

The problem, of course, is that the evidence indicates that Americans are not polarized along party lines – at least not any more than they were five decades ago. Indeed, if anything, they are perhaps less polarized, particularly when it comes to cultural issues. Here are two charts, courtesy of Stanford political scientist Morris Fiorina, that show the partisan and ideological trend lines among Americans during the period 1952-2008. Let’s look first at partisanship.

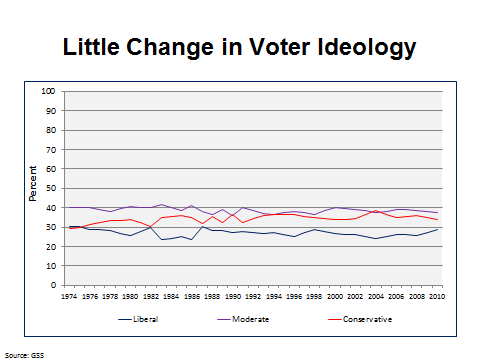

The data show a similar story for voter ideology.

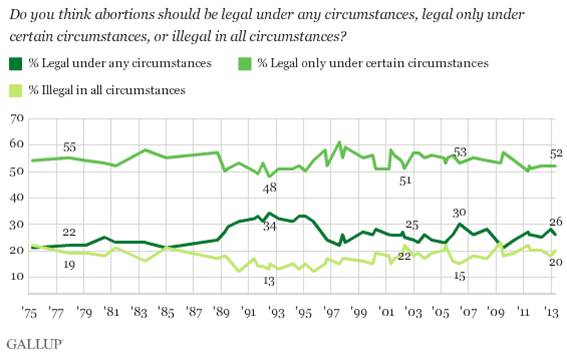

As you can see, then, the trend lines indicate that the number of Americans who self-identify as independents (including leaners) is on the rise, albeit slightly, across the last five decades, while the portion of self-identified moderates (again including leaners) has remained largely stable. This is hardly the picture of an increasingly polarized people. We find similar patterns when we ask Americans their views on key cultural issues, such as abortion.

As you can see, opinions toward abortion have barely budged since Roe v. Wade was decided almost four decades ago. During that entire period, most Americans support the middle way on abortion rights.

As you can see, opinions toward abortion have barely budged since Roe v. Wade was decided almost four decades ago. During that entire period, most Americans support the middle way on abortion rights.

And while Fineman is correct that the cable news shows do present two diametrically different portraits of the political world, the reality is that even the most popular such shows draw proportionally few viewers. Bill O’Reilly’s “The O’Reilly Factor” on Fox, one of the most popular political talk shows on cable, draws about 3.5 million viewers on an average night. Rachel Maddow may draw .5 million on a good night. But 12 million viewers watched the season premiere of Duck Dynasty on cable, and about 8 million watched this epic shot by Big Papi:

[youtube 3nhIr0wJJ-Q?]

Polarized? Not among Americans. And not here in Red Sox Nation.

And really, aren’t they the same thing?

Hi!

Even if we accept the Fiorina argument about polarization not increasing (and we don’t have the last five years of data, remember, so I don’t think that’s worth conceding anyway), there’s no disputing geographic partisan sorting–even if we only care about the so-called “political class”. That geographic echo chamber (coupled with the media echo chambers we all now live in) exacerbates the extremism of the political class. So, you can both be right!

Plus, because of geographic sorting (AND ALSO GERRYMANDERING) districts are less moderate, by PVI. So there is more incentive than ever to pay attention only to the political class. Which makes it worse. And you’re still both right.

Right?

Hi Charlie,

Actually, the latest survey data suggests that the media might finally be acknowledging what we have been arguing for many years now – that rather than becoming more polarized, Americans are retaining their moderate perspective. See: http://nbcnews.to/1cnC0wc (Note that the article is by journalists, so they have to say that the ideological chasm is suddenly shrinking, rather than acknowledging that it never existed, but we have to take what we can get!) In any case, once you talk about the “political class”, you are essentially conceding my point: that media reports about a polarized electorate are fundamentally wrong. Thus, we aren’t both right – Political scientists are right, and the media is wrong. Why is that so hard to accept?

Charlie,

The other point I would make is that in fact I do dispute your claim of partisan sorting by residence. The best evidence I’ve seen suggests we are not increasingly sorting into neighborhoods of like-minded people. It may seem that way because when you are at a cookout and you mention how much you detest Party X, a Party X supporter is probably not going to raise an objection. So you are probably underestimating just how heterogeneou neighborhoods are, politically speaking. Similarly, most of us do not get our news solely from partisan news sources on cable or on the internet. And, at the risk of repeating myself, there’s not much evidence that gerrymandering is contributing to polarization.

Professor Dickinson and Charlie –

I would like to chime in solely to say that I missed these exchanges dearly (which, of course, Professor Dickinson always wins) and am glad that they can continue on the blog.

Also, that grand slam was epic. Go Sox!

Anna – I miss them too! Of course, it’s not about winning (unless we are talking Big Papi) – it’s about challenging our assumptions! Consider these exchanges part of the virtual seminar…. .

Not disagreeing that the broad middle still exists, and that it’s great the media is–to an extent–coming around. So I’m not disputing the main thrust of the post. All I’m saying is that the increase of polarization in Congress is still related to geography, because the political classes are polarizing and doing so to a large extent along geographic lines. (Plus gerrymandering, more homogeneous districts by PVI, etc.) Even if most Americans are as moderate as ever, their congressional districts just aren’t.

“The best evidence I’ve seen suggests we are not increasingly sorting into neighborhoods of like-minded people. It may seem that way because when you are at a cookout…” There we disagree. Election data shows that more Americans than ever are living in precincts where one candidate gets 60+% of the vote. And while I don’t have numbers for this, there is no way that the Internet hasn’t made people get their news from more partisan sources–even if that hasn’t changed for folks over age X, among “the youth” it is undoubtedly the case…

Also, any thoughts on the lack of data since 2008? Do you think that’s changed at all?

Anna, thanks for your witty contributions to the comments section.

Charlie – It’s not clear to me what you mean when you say congressional districts are polarizing – at times you seem to refer to those who represent those districts, but at other times you reference the increase in number of districts in which one candidate gets 60% or more of the vote, thus implying that voters are more polarized. But the increase in “safe” districts is not evidence of polarization among voters – it is evidence of polarization of choices! What you are seeing is the effect of party sorting.

As for gerrymandering causing polarization – if you don’t want to read the article I linked to, then just repeat to yourself: Senate, Senate, Senate! As a alumn of PS 429, you’ll understand the reference (I hope!)

Welcome back Prof. Dickinson,

I’m not able to speak to the statistics, but I think one of Charlie Arnowitz’s point sounds reasonable. Basically, there is a disconnect between what you’re describing as a moderate electorate, and what most people view as its polarized representatives.

You may not see this misrepresentation as a disconnect or maybe you do. Is it naive to think that a polarized government should return to a more accurate representation of its electorate? Or, if the moderate electorate keeps being represented by polarized politicians, is it moderate in intent only and not its deeds? A last question, is there a measurement for how unrepresentative a government is of its electorate, and would the current polarized government be particularly misrepresentative?

Thanks,

Adam