Last night’s Democratic debate in Detroit offered two distinct visions for the future of the Democratic Party, and of the nation more generally. The two progressives, senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, shared center stage literally and figuratively, collectively making the case that it is time for big ideas to reform the political and economic system, including Medicare-for-All; more restrictive trade agreements, higher minimum wage, a more progressive tax system, free college tuition, and immigration laws that don’t criminalize those entering the country illegally. In contrast, the pragmatists – who included almost everybody else on the stage (Pete Buttigieg and Beto O’Rourke are more difficult to categorize although on many issues they seem closer to the progressive wing) – chided the Big Two for, as former Maryland Representative John Delaney put it, pushing “fairy tale economics.” Similarly, Montana Governor Steve Bullock chastised what he called the progressives’ “wish-list economics.” And Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar, after blasting the progressives’ health care and college tuition plans, warned that her colleagues on stage seemed “more worried about winning an argument than winning an election.” But the progressives pushed back, arguing that the pragmatists were pushing “Republican talking points.” As Warren put it, “I don’t understand why anybody goes to all the trouble of running for president of the United States just to talk about what we really can’t do and shouldn’t fight for.”

Who had the better argument? Polling suggests that pluralities of voters are skeptical of some of the progressives’ more ambitious policy proposals. Ohio Representative Tim Ryan alluded to this when he warned, “…in this discussion already tonight, we’ve talked about taking private health insurance away from union members in the industrial Midwest, we’ve talked about decriminalizing the border, and we’ve talked about giving free health care to undocumented workers when so many Americans are struggling to pay for their health care. I quite frankly don’t think that that is an agenda that we can move forward on and win.” However, Sanders and Warren believe that the president’s job is to lead public opinion – not be limited by it.

Political science can’t help voters make a choice between these two paths. But it can potentially shed some light on the electability argument. Are more ideologically extreme candidates less electable? As Seth Masket tweeted earlier today, there’s plenty of evidence suggesting the answer is yes – that moderates do perform better at the polls, at least in House elections. As an example, in previous posts I’ve talked about the electoral price Democratic incumbents who voted for Obamacare paid at the polls during the 2010 midterms. That policy was viewed as relatively extreme at the time and helped contribute, along with Democrats’ votes in Congress on the stimulus bill and climate change legislation, to the rise of the Tea Party movement and the Republican takeover of the House in the 2010 midterm elections. Moreover, the Obamacare example is consistent with a broader finding by Andrew Hall showing that parties pay a clear electoral price when they nominate extremist over more moderate candidates. Looking at House elections from 1980-2010, Hall calculated that “when an extremist—as measured by primary-election campaign receipt patterns—wins a ‘coin-flip’ election over a more moderate candidate, the party’s general-election vote share decreases on average by approximately 9–13 percentage points, and the probability that the party wins the seat decreases by 35–54 percentage points.”

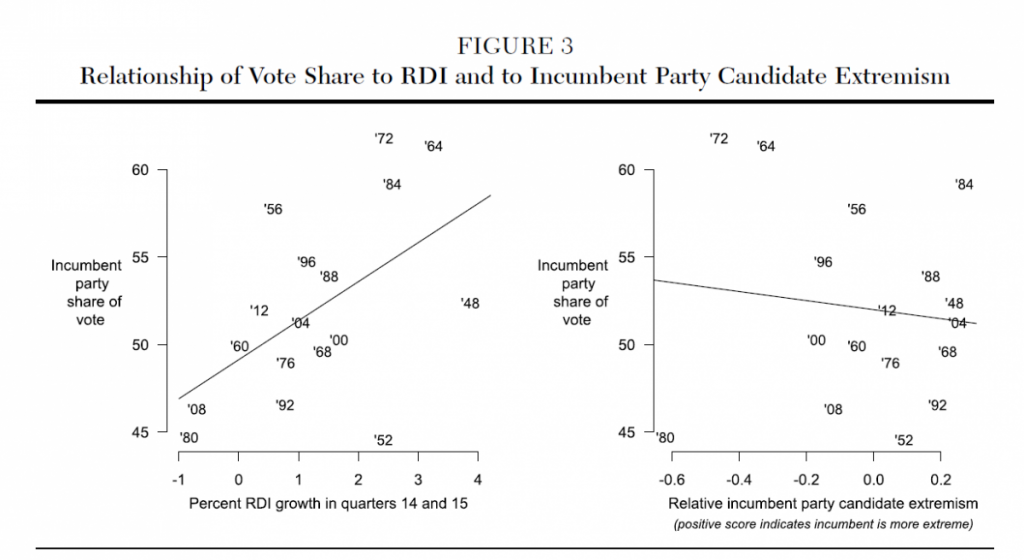

However, it is unclear whether ideological extremism costs presidential candidates, at least during the general election. At least one study by Cohen et al., indicates that more ideologically extreme presidential candidates did NOT pay an electoral price at the voting booth during the period 1948-2012, once you control for other factors influencing election outcomes. The chart below captures their findings. It shows a strong positive relationship between economic growth and the incumbent party’s popular vote share, but a weaker one between vote share and the relative incumbent party ideological extremism. While I’m not sure I agree with the interpretation of the results, their research should give one pause about using House elections to generalize about presidential results.

Of course past performance is no guarantee of future results. It is perhaps telling that the pragmatists’ embrace of the public option is now viewed as the moderate alternative to the progressives’ preference for Medicare-for-All; in 2009, Obama dropped the public option from his health care legislation when it became clear it was viewed as too extreme to pass the Senate. Clearly, the Democratic Party has shifted left in the ensuing decade – but how far left, and has the broader public moved with them? We are about to find out!

A couple of thoughts as we head into tonight’s debate.

In my experience, normal people don’t generally look at debates in terms of who “won” or “lost.” Rather, they tend to discuss what they heard from specific candidates on particular issues, and whether they agreed with it or not. Here I’m using “normal” in its statistical sense to reference the majority of people who have neither the time nor inclination to obsess about which debaters’ comments went “viral” or what a talking head on cable television said about the meaning of what just transpired. What normal people want from a debate is some idea of what the candidate believes, and how they plan to govern. Of course, this is not to say that the subsequent framing of a debate by pundits has no impact – if enough analysts agree on a key debate theme or takeaway, that conventional wisdom can shape public opinion – up to a point. Nonetheless, those instant takes can be misleading. So, if you plan on watching tonight’s debate, I urge you to turn off your social media feed while doing so, lest you succumb to the idea that those on twitter, Facebook and other interweb platforms somehow represent what normal Americans are thinking. They do not. Instead, listen to what the candidates actually say – not what the chattering class tells you they are really saying.

In that vein, I think anyone who watched last night’s debate carefully came away with a clear sense of the quite different choices facing them in the fight for the Democratic presidential nomination. At least part of the credit for that should go to the CNN moderators who did a decent job encouraging the candidates to talk to one another in a way that highlighted policy differences, even if the candidates were not given enough time to fully explain those differences. In this respect, the real winners last night were the voters.

As for tonight – I expect a slightly different dynamic. To be sure, as we saw with Bernie last night, I fully expect Biden to come out far more energized and aggressive compared to the first debate, where he appeared somewhat surprised at Kamala Harris’ decision to confront him regarding his opposition to federally-mandated forced busing to integrate public schools back in the 1970’s. And make no mistake – Biden, and to a lesser extent Harris – have a giant target on their backs, as second-tier candidates (I’m looking at you, Bill de Blasio!) trying to insure a place on the September debate stage will undoubtedly try to score points at the front-runners’ expense, much as the pragmatists – all of whom are polling in low single digits – did last night. The difference is that Biden is not just the frontrunner – he’s also closer to the pragmatists, particularly on the electability issue. So I expect the shoe to be on the other foot tonight, with Harris, Booker and Castro making the case that Biden’s time is past, and that they represent the future of the Democrat Party, demographically and ideologically. For his part, I expect Biden to reprise the pragmatists’ electability argument from last night, while wrapping himself in the comfortable blanket of the Obama presidency.

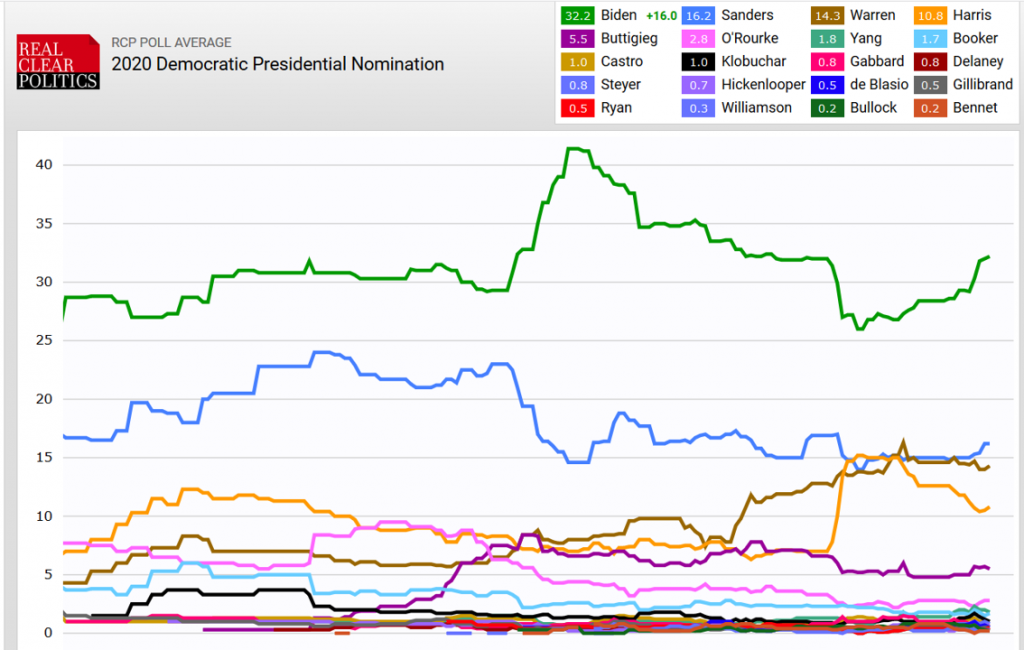

Second, we shouldn’t overreact to short-term movements in polling numbers based on either or both of these two debates, despite pundits’ constant efforts to identify “game changing” moments. Many analysts decided Harris had “won” the first debate due to her highly-publicized exchange with Biden regarding his views on forced busing. And, initially, that analysis seem validated by Harris’ poll numbers, which spiked in the immediate aftermath of the debate, while Biden’s went down. But as we see in the RCP poll, she’s since lost about half of that surge, and Biden’s numbers are back up to about where they were before the debate.

In short, beware of instant punditry – particularly the kind practiced by the cable news commentators who need to fill time after the debate is over.

So where should you go to understand what happened tonight? Move on over to Channel 3 to watch my live post-debate analysis and, not incidentally, gauge the progress of my living room ceiling repairs!

I really like that you touched on how extremists are usually detrimental to a party getting elected. My brother and I are starting to get more into politics and we want to start backing candidates we like. I’ll keep your article in mind so that we learn more about which candidates we should donate to so they are successful.