Vox founder Ezra Klein posted this diatribe last week explaining why he believes “moderate voters are a myth” that was extreme even by Ezra’s standards. Drawing on this draft paper by Douglas Ahler and David Broockman, Klein argues that the notion of moderate voters is a statistical artifact that occurs when researchers aggregate responses to several survey questions into a single ideological scale. So, greatly simplified, the idea is that if an individual gives a very conservative answer to one question, and a very liberal one to another, the “index” based on these responses might classify her as a “moderate” by, in effect, balancing the two extreme responses. But in fact all the survey responses show is that she has diverse but extreme opinions – not moderate ones.

In principle, Klein’s criticism is correct. Indeed, scholars have long been aware of this problem when it comes to creating indexes of ideology. Note, however, that it is not only a problem with indexes that purport to show that voters are mostly moderate – other indexes professing to show that Americans are becoming more polarized also suffer from similar coding issues. (In this vein, see this Fiorina, Abrams and Pope’s critique of this Abramowitz/Saunders article on ideological realignment in the United States. Their essential point is that slight movement in responses to one question can, depending on coding, make it appear that voters are changing positions from moderate to extreme on an ideological index .)

Had Ezra stopped there with a caution to be careful about interpreting indexes that purport to measure ideology, I would have been happy. But he doesn’t. Instead, Ezra goes on to dismiss the idea of a moderate middle entirely: “The deeper point here is that the idea of the moderate middle is bullsh*t: it’s a rhetorical device meant to marginalize some policy positions at the expense of others. There’s no actual way to measure it, or consistent definition animating it, and it doesn’t spontaneously emerge in any of the data.”

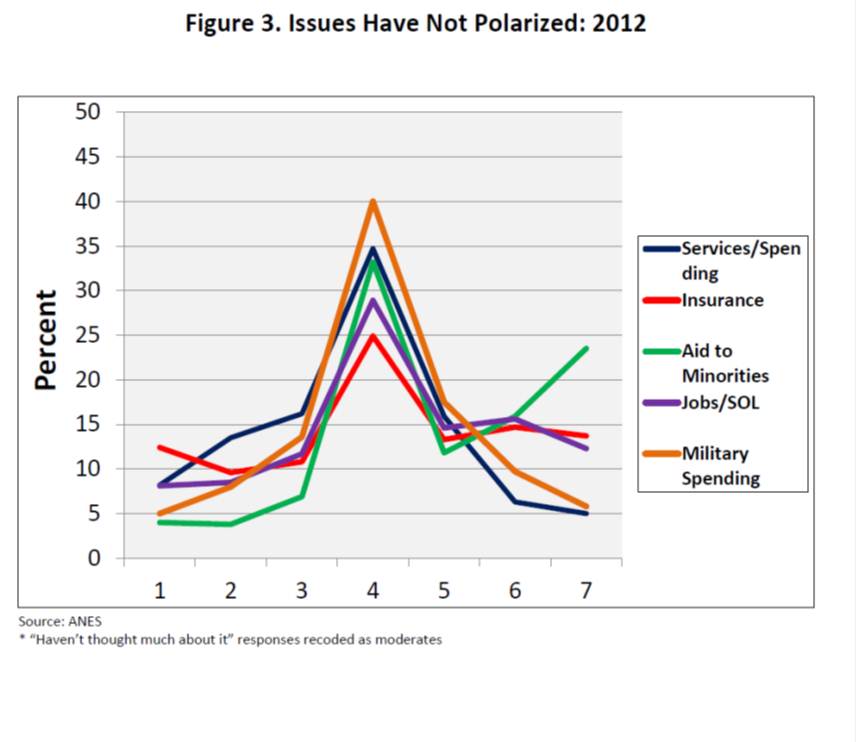

I’ll have more to say about the Ahler/Broockman paper in another post. (By way of preview, I think their findings actually support the notion of a moderate middle.) But the notion that the existence of a moderate middle is “bullsh*t”, to use a scientific term is, well, cow dung. Even if many Americans hold inconsistent views, and thus it is hard to classify them ideologically does not mean that on most issues the preferred position among Americans is an ideologically extreme one. Consider, for example, this analysis by Abrams and Fiorina regarding the distribution of responses from 1 to 7 to five policy questions asked by the American National Election Studies in 2012. (Typically, the questions lay out two alternative policy positions on an issue, such as whether the government should or should not make an effort to help the social and economic standing of African-Americans, and asks respondents to place themselves on a 7-point scale in terms of where they stand on the issue. Position 4 is the most moderate one, with 1 and 7 holding down the extremes.)

As you can see, the modal response to questions asking where the respondent stands is the moderate one on all five issue areas. (Note: the authors code the “don’t know/haven’t thought about it” as a moderate response based in part on comparing responses with other surveys that do not include these response options, and finding little difference in the distributions of responses.) Nor is this unique to 2012. Day Robins went back and looked at responses to these questions through several decades and found that for almost every survey the modal response on these five issues is the middle, or moderate, one. I’ll show some of this data in graphical form in a separate post.

As you can see, the modal response to questions asking where the respondent stands is the moderate one on all five issue areas. (Note: the authors code the “don’t know/haven’t thought about it” as a moderate response based in part on comparing responses with other surveys that do not include these response options, and finding little difference in the distributions of responses.) Nor is this unique to 2012. Day Robins went back and looked at responses to these questions through several decades and found that for almost every survey the modal response on these five issues is the middle, or moderate, one. I’ll show some of this data in graphical form in a separate post.

This is not the same as showing that at the individual level voters are mostly moderate, of course. It could be that different moderate coalitions consisting of different individuals show up on each issue. On the other hand, it doesn’t justify dismissing the idea of a moderate middle either, at least when it comes to choosing policy options in a number of issue areas. As Philip Bump reminds us, we need to be careful when we adopt short-hand language for any concept. But while Klein is right to point out the dangers of creating indexes to measure ideology, when it comes to the American voter I’m not ready to throw out the concept of a moderate middle in its entirety. That would be too extreme.