Part of American’s fascination with the extended and lavish celebration of Queen Elizabeth’s 60 years on the throne is rooted, I think, in the lack of any equivalent royalty in our country. (I don’t count King [Lebron] James. Particularly after Sunday’s dismal overtime performance and subsequent whining about the officiating. Nor the Kardashians. Maybe Elvis but, alas, he’s left the building.) Indeed, our Constitution explicitly prohibits the government from conferring royal status on anyone; Article I, section 9 states that “No Title of Nobility shall be granted by the United States.” That prohibition reflects a core element of the American political creed – the idea that we are all social equals. Americans tend to believe this, at least as an aspiration. And it’s why our political candidates spend so much time trying to convince us that they are just regular people, even when they are not.

A less well appreciated aspect of that prohibition against titles of nobility, however, is that we have no equivalent of the Queen in our country – no nonpartisan figure who can serve as a unifying symbol of the country. The public embrace by the British of their Queen during these last few days reminds us that despite their foibles and other all-to-human qualities, the royals – particularly the Queen – embody national sovereignty. The British don’t ask God to save the Prime Minister, after all.

Lacking royalty, we have entrusted the head of state functions to the one person that, by virtue of having a national constituency, comes closest to embodying national sovereignty: the President. The combination of the two functions – chief executive officer of the government and head of state – within one individual can be, under certain circumstances, a potent tool that enhances presidential power. This augmentation of presidential power is most likely to occur when the president’s political preferences align with the national interest, as defined by a vast majority of the people. Under those circumstances, the president’s actions are perceived to be addressing broader issues than mere partisan gain – even when they also help the president politically.

A case in point is President Clinton’s nationwide speech in the aftermath of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing by Timothy McVeigh, a right-wing antigovernment extremist. At that point in his presidency Clinton was fighting for his political life due to the historic Republican takeover of Congress in the 1994 midterm elections. Clinton’s speech eulogizing the victims was part of the national mourning process. In his book POTUS Speaks, Clinton’s speechwriter Michael Waldman writes, “For many people, during those days, for the very first time, [Clinton] truly became a president.” But , as Waldman also acknowledges, the speech gave Clinton political leverage: Clinton “saw the political opening the bombing had created, for while Timothy McVeigh was planning an anti-government explosion in the heartland, the Republican in Congress were planning an anti-government “Republican Revolution” in Washington.” For Waldman, the Oklahoma City speech was a turning point in Clinton’s presidency – the moment when he used his ceremonial duties to enhance his political prestige. We can quibble with the relative impact of the Clinton speech versus a strengthening economy in explaining Clinton’s political resurgence (I’ll take the economy), but Waldman’s larger point remains: presidents can gain politically when they perform the ceremonial functions associated with serving as head of state. George W Bush found this out in the days immediately after 9-11.

But there are risks inherent to performing these ceremonial functions, as Barack Obama found out when he gave this speech in January 2011 eulogizing the victims of the Arizona shooting.

[youtube /v/ztbJmXQDIGA?version=3&feature=player_detailpage”><param name=”allowFullScreen” value=”true”><param name=”allowScriptAccess” value=”always”>]

Although Obama’s speech was generally well received, the event became caught up in a larger partisan-tinged debate regarding whether Sarah Palin’s heated rhetoric along with her infamous map putting gunsights over congressional districts she was targeting had somehow created a climate that contributed to the Arizona shootings. Given those partisans overtones, some critics suggested that Obama’s speech was more a political pep rally than a eulogy. The debate diminished some of the impact of Obama’s speech by casting it in a more political light than he likely intended.

It is also the case that the President’ s head of state function can serve to further U.S. national interests abroad. Perhaps the most famous example occurred during FDR’s presidency when, on the eve of World War II, King George VI became the first British monarch to visit the United States. By inviting the King, Roosevelt hoped to personalize the British monarchy, thus bolstering domestic support for stronger ties to Great Britain. The visit was an unbridled success as crowds lined the streets of Washington DC to watch the King and Queen as they visited national landmarks including the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier.

The highlight of the four-day visit, however, was the picnic the President held at his home in Hyde Park, New York. There, in a distinctly American touch that horrified some, the President – no plebian, mind you – served the Royals hot dogs while sitting on the front porch of a Roosevelt cottage. Here’s the lunch menu, according to the FDR Library website:

MENU FOR PICNIC AT HYDE PARK

Sunday, June 11, 1939

Virginia Ham

Hot Dogs (if weather permits)

Smoked Turkey

Cranberry Jelly

Green Salad

Rolls

Strawberry Shortcake

Coffee, Beer, Soft Drinks

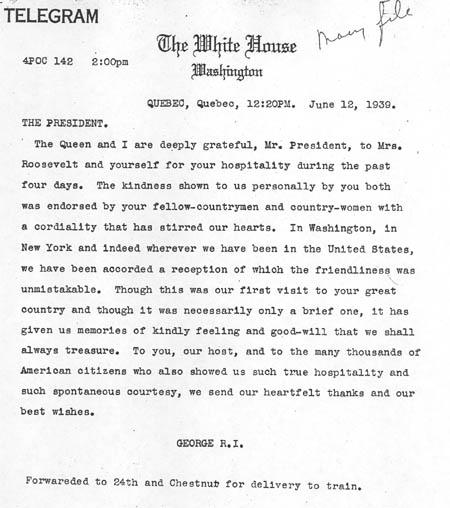

To their credit, the King and Queen seemed to enjoy the fare, and the visit more generally, as this telegram indicates.

More importantly, the visit helped win over the American people so that when three months later Great Britain declared war on Germany, Roosevelt had stronger – although certainly not unlimited – domestic support for intervening on the British behalf.

By virtue of serving as head of state, then, a president can, under certain circumstances, enhance his political standing. But there are risks to engaging in these functions if the public perceives them as primarily motivated by political interests. Rather, they are most potent when they flow naturally from the functions we associate with being head of state, rather than as leader of a political party.

In contrast, precisely because her actions are not tinged by partisan considerations, the Queen’s ceremonial functions are both more important and more accepted by almost all of her subjects. She truly does embody national sovereignty in a way that American presidents cannot.

Perhaps Johnny Rotten, of the Sex Pistols, put it best in their best-selling song “God Save the Queen” released during Queen Elizabeth’s silver jubilee in 1977:

“God Save the Queen. She Ain’t No Human Being.”

[youtube /v/sR8dhUfoj-s?version=3&feature=player_detailpage”><param name=”allowFullScreen” value=”true”><param name=”allowScriptAccess” value=”always”>]

Ok, maybe not.