Will the results of the January 3 Iowa caucus even matter to the outcome of the 2012 Republican presidential nomination? My colleague Bert Johnson and I have discussed this matter here. Bert’s basic point is that the Iowa caucus helps voters solve what he calls a coordination problem, in which those who share a similar ideology and policy preference must decide which candidate to coalesce behind. In so doing, they give that candidate “momentum” going into later contests. Bert’s claim is consistent with conventional wisdom among political scientists which argues that Iowa’s significance lays not so much in who wins the caucus as it does in who loses. Simply put, those who fail to meet expectations drop out of the race, thus helping solve the coordination problem.

While I don’t disagree with the basic logic that says early nomination contests help winnow the field, the historical record indicates that Iowa has not played much if any role in that winnowing process. In looking at previous Iowa caucus results dating back to the start of the modern primary-centered nominating process in 1972 there has been only one year by my admittedly back-of-the-envelope calculation where the results in Iowa have served to directly winnow the field in significant numbers. As the table below indicates, that would be the Democratic contest in 2008, which eliminated three candidates of the six Democrats actively campaigning there: senators Joe Biden and Chris Dodd, and Governor Bill Richardson. (Note: I only included candidates who received 1% or more support in the Iowa caucuses.)

| Year | #Democratic Candidates | # Who Withdraw After Iowa | # Republican Candidates | # Who Withdraw After Iowa |

| 1972 | 6 | 0 | No Republican contest | – |

| 1976 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 1980 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| 1984 | 7 | 0 | 1(Reagan Unopposed) | – |

| 1988 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| 1992 | 5 | 0 | 1 (G. H. W. Bush Not Challenged in Iowa) | 0 |

| 1996 | 1 ( B. Clinton Unopposed) | – | 8 | 0 |

| 2000 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| 2004 | 5 | 1 | 1 (G. W. Bush Unopposed) | – |

| 2008 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 0 |

In most years, however, the Iowa results do not seem to precipitate a significant number of withdrawals. Indeed, in 15 contested caucuses since 1972 involving 80 candidate-races, only six candidates dropped out as a result of doing poorly in Iowa.

Now, this may underestimate Iowa’s actual impact on the nominating process. To begin, I don’t count those candidates, like Tim Pawlenty this year, who drop out before the caucuses are held because they perceive a lack of support in Iowa. Moreover, candidates who exceed expectations in Iowa may receive a boost in support down the road, and those who fail to clear the expectation bar may see their subsequent support decline. But strictly speaking, the vote in the Iowa caucuses rarely culls the candidate herd in large numbers by itself. Indeed, in most years it has no impact on the size of the field whatsoever.

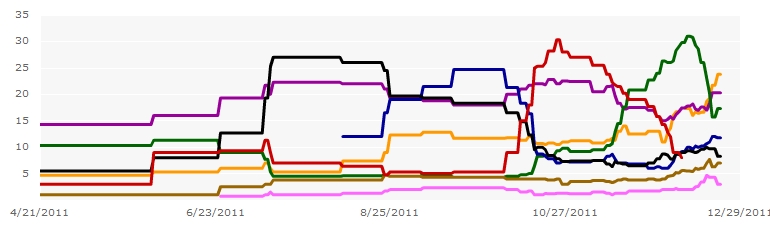

So, what does this suggest come January 3? Two more Iowa polls came in during the last two days. This Rasmussen poll has Romney leading the field with 25%, followed by Paul at 20% and Gingrich at 17%. A second poll commissioned by Iowa St. has Paul as the first choice of 27.5% of those surveyed, followed by Gingrich at 25.3% and then Romney at 17.5%. Of greater relevance to this post, however, both polls showed Bachmann and Santorum trailing the field among active candidates. (Perry is 4rth in both.) These results are consistent with the latest RealClear Politics composite poll, which shows only Bachmann, at 8.3%, and Santorum, at 7% as polling in single digits in Iowa. (Santorum is black and Bachmann brown in the graph below. Huntsman, in pink-purple at the bottom, is not actively campaigning in Iowa.)

Assuming they finish as the bottom two in Iowa, will either Bachmann or Santorum drop out? With the New Hampshire primary one week later, on January 10, my guess is both may stay in to see whether social conservatives will decided to coalesce behind one or the other of them, thus giving that candidate a boost heading into South Carolina. Unfortunately, New Hampshire is not a particularly hospitable climate for their brand of political conservatism, which means one or both might decide to continue even if they do poorly in New Hampshire. All this assumes, of course, that they have enough money to do so.

Make no mistake about it. The Iowa caucus will be a huge media event. It is less likely, however, that it will be a significant political event that helps to winnow the field. Indeed, if history is a reliable guide, at least six and possibly all seven Republican candidates now in the race are likely to be still in the contest after Iowa. Is Iowa relevant? Yes. Decisive? Probably not.

But is the act of candidates dropping out of the race a good indication of Iowa’s role in winnowing the field? If your colleague is right that it helps address the coordination problem, it can do that whether or not individual candidates (with individual egos) choose to stay in the race. Especially with the proportional division of delegates in the early races, it’s easy to imaging candidates justifying their decision to keep running even after the Iowa results have directed potential supporters to a more ‘viable’ candidate. The mere fact of their remaining in the race doesn’t seem to be a very good indicator of Iowa’s role. It would be much more helpful if pollsters over the next week or two included a question of who voters *had* supported, so we could try to see that coordination problem being worked out in real time.

Jason,

You are right and I didn’t mean to suggest otherwise. As I wrote, “Moreover, candidates who exceed expectations in Iowa may receive a boost in support down the road, and those who fail to clear the expectation bar may see their subsequent support decline. But strictly speaking, the vote in the Iowa caucuses rarely culls the candidate herd in large numbers by itself. Indeed, in most years it has no impact on the size of the field whatsoever.” So, even before Republicans adopted proportional allocation, Iowa did serve a coordinating function by signaling which candidate(s) were likely to be culled in the future, even if they chose to remain in the race despite finishing back in the Iowa pack. The winnowing process that began in Iowa often culminated with the trailers dropping out after New Hampshire. I was making a narrower point designed to push back against the idea that in this election cycle the field of candidates will narrow after Iowa. Strictly speaking, that hasn’t been the case in past years and, as you point out, it may be even less so this time around with the proportional allocation of delegates in place. In the end, however, those with deep pockets will play a major role in deciding who gets winnowed and when.