Trustee or delegate? It is the classic dilemma every elected official faces. Political scientists are fond of reminding their students that Edmund Burke once explained to his constituents that as a member of Parliament he would be a trustee, not a delegate; that is, he would vote his conscience, rather than simply doing what his constituents wanted. “Your faithful friend, your devoted servant, I shall be to end of my life, [but] a flatterer you don’t wish for.” Burke promptly lost his bid for election.

It is not clear whether House Democrat Dan Maffei, who conceded his race in New York’s 25th district to Tea Partier Ann Marie Buerkle on Tuesday, knew of Burke’s fate. As Jeff Garofano reminds me in an email, Maffei’s seat had been reliably Republican for several decades – as had been much of upstate New York – until Maffei won it for the Democrats in 2008. Once in office Maffei supported the Democratic leadership on a number of controversial votes. In his concession letter, Maffei – much like Burke! – expressed few regrets: “Not only do I not apologize for my positions on the stimulus, the health care bill, financial reform, and the credit card bill, but my only regret is that there were not more opportunities to make healthcare more affordable to people and businesses and get more resources to the region for needed public projects – particularly transportation and public schools. I am also deeply proud of my commitment to energy reform and mitigating global climate change.”

Maffei may be proud of his votes – he was no flatterer! – but in the end his seat became, by my unofficial count, the 63rd lost by Democrats in this election cycle, pushing the overall House totals to 242 Republicans and 192 Democrats. And, as I discuss below, there is evidence suggesting that the votes about which Maffei expresses such pride may have cost him – and Democrats more generally – their seats.

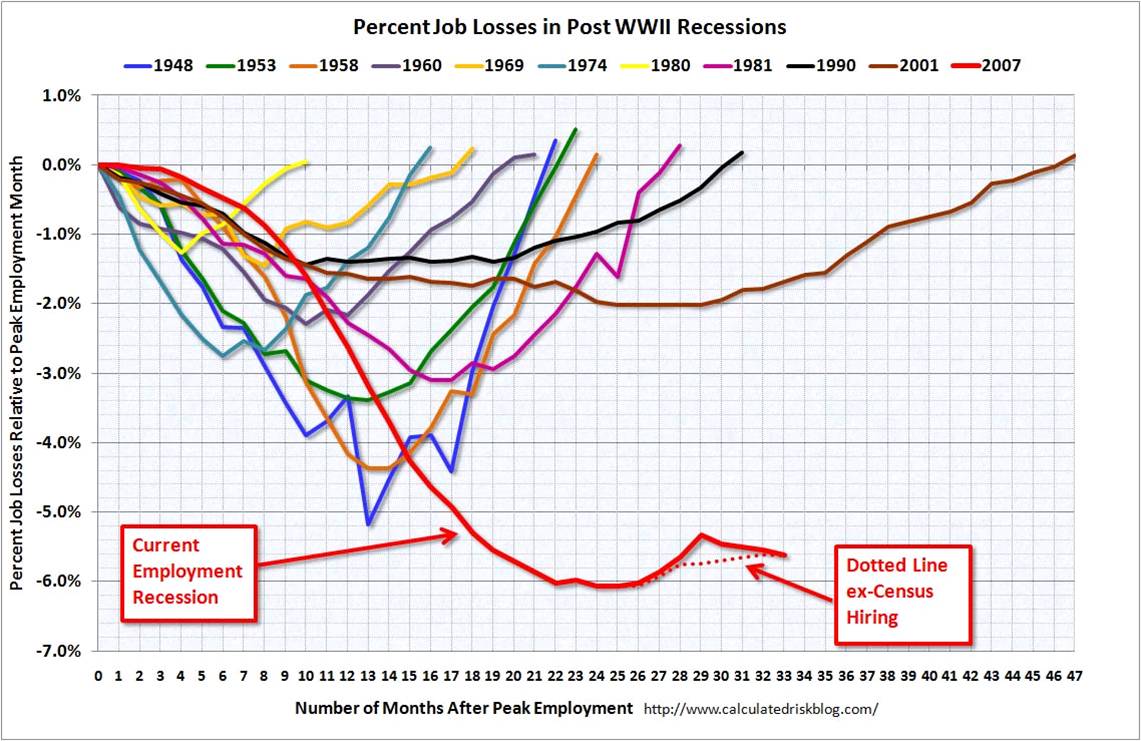

To be sure, as I argued in my last post, the size of the Republican wave that washed so many Democrats like Maffei out of office was largely due to the unprecedented nature of the economic recession. In that vein, Mo Fiorina passes along the following chart:

As you can see by the red line, the depth and duration of the current jobless cycle is unprecedented in the post-Depression era. I also suggested in that previous post, however, that some Democrats, like Maffei, paid a price for their votes on a number of high profile issues, such as health care. In this vein, Bill Galston finds based on polling data that 17% of midterm voters cited health care as the biggest influence on their vote. “Of those voters, 58 percent had an unfavorable view of the health-reform law, 58 percent thought it would make the country worse off, and 56 percent thought it would leave them and their families worse off. Not surprisingly, health care voters went for Republican over Democratic candidates by a margin of 59 percent to 35 percent. (Non health-care voters were divided 44 percent to 44 percent.)”

But can we be sure that support for health care, or other controversial high-profile issues like TARP, the stimulus bill or cap and trade, really cost Democrats seats? A number of political scientists have sought to look more systematically at the electoral effect, if any, in 2010 on Democrats who supported these issues. One such study by Eric McGhee and John Sides analyzed the estimated impact of a Democrat’s support for cap and trade, the stimulus bill and health care, and the impact of supporting only health care and cap and trade, while controlling for the district’s previous House vote, presidential support in 2008, and campaign spending by candidates. As the following two charts indicate, they estimate that in the aggregate support for the stimulus bill, health care and cap and trade cost the Democrats 35 seats, while a vote for just health care and cap and trade cost 24 seats. (The charts compare the actual results with the estimated results if Democrats had voted against the controversial bills.)

They calculate the average loss of support for Democrats per controversial vote as follows: 2.8% for the stimulus, 2.1% for cap-and-trade, and 4.5% for health care. Of course, the estimated loss varies across each district, although it tends to increase as districts become progressively more Republican. They conclude that the net impact on Democrats of just these three controversial votes might have been enough to cost them control of the House. These estimates, of course, are subject to a large margin of error (the red lines in the charts above). Moreover, as Jonathan Bernstein points out, we can’t really be sure what would have happened in the absence of the health care vote, or the absence of any of these votes for that matter, because the context of the election most assuredly would have changed without these votes. Finally, one might conclude, as Maffei evidently did, that passing health care or the stimulus package was worth the political cost of losing one’s seat, not to mention majority control in the House. In the case of the stimulus bill, or TARP, one might argue that Democrats had no choice but to support both pieces of legislation – otherwise the banking industry might have collapsed and the economy might have gone into a deeper recession. As McGhee and Sides remind us, however, Democrats certainly had the option not to push for health care reform, or cap and trade legislation.

They calculate the average loss of support for Democrats per controversial vote as follows: 2.8% for the stimulus, 2.1% for cap-and-trade, and 4.5% for health care. Of course, the estimated loss varies across each district, although it tends to increase as districts become progressively more Republican. They conclude that the net impact on Democrats of just these three controversial votes might have been enough to cost them control of the House. These estimates, of course, are subject to a large margin of error (the red lines in the charts above). Moreover, as Jonathan Bernstein points out, we can’t really be sure what would have happened in the absence of the health care vote, or the absence of any of these votes for that matter, because the context of the election most assuredly would have changed without these votes. Finally, one might conclude, as Maffei evidently did, that passing health care or the stimulus package was worth the political cost of losing one’s seat, not to mention majority control in the House. In the case of the stimulus bill, or TARP, one might argue that Democrats had no choice but to support both pieces of legislation – otherwise the banking industry might have collapsed and the economy might have gone into a deeper recession. As McGhee and Sides remind us, however, Democrats certainly had the option not to push for health care reform, or cap and trade legislation.

In short, although profiles in voting courage may provide material for Pulitzer prize-winning books, it is likely that because of these votes Republicans now control the House, and are poised to take the Senate in 2012. If they also win the presidency, who knows whether health care will even survive? So, were these votes worth the electoral pain they inflicted? Unfortunately, elected politicians don’t have the luxury of hindsight when trying to estimate likely voter reaction to how they vote. Maffei may now tell his constituents that he is proud of his votes, and he may even believe it. On the other hand, what else can he say? “Wait! I want a do-over! Health care was a horrible piece of legislation!” My guess – and it is only a guess – is that if he knew these votes would cost him his seat, he would have voted no on several of them. Instead, his district is now represented by a Tea Partier who is certain to try to undo all the legislation Maffei supported.

That brings me to the final element in my post-election analysis: the impact of the Tea Party. I’ll address that in my next post.

With the issues of the stimulus, the cap-and-trade system, and the Health care bill, one of the major issues was the lack of a strong push by Democrats. I think that Republican delaying tactics significantly weakened the bills, as did the less-than-dramatic results. Too much of the stimulus was spent on tax cuts to try to gain non existent Republican votes; too little was spent on infrastructure spending and other items that could further help cut unemployment. Tax cuts don’t have nearly as much of a multiplier as direct spending.

Zach – You may be right regarding the relative efficacy of tax cuts versus government spending when it comes to stimulating the economy. Politically, however, the Democrats had little choice but to meet at least some of the Republicans half way – as I recall, without Snowe and Collins there’s no bill at all. Tax cuts was the price these Republicans extracted. Note that comparatively speaking, the stimulus bill passed rather quickly.

Health care was a different animal – here the long drawn out legislative process certainly cost Democrats in terms of public support for the legislation. But I’m not sure what they could have done differently, particularly after Brown’s win in Massachusetts.