Several posts ago I defended the existence of the Senate filibuster, which has come under fire from liberals because of its impact on the health care debate. My argument rested on three points:

1. That the increased use of the filibuster during the last half-century reflects not just the growth in partisan polarization in Congress, but also the lowered cost of threatening to filibuster. Senators are much more willing to simply invoke cloture to forestall a threatened filibuster, which means filibustering a bill is a less time consuming process than it once was. This concern with efficiency is a function of the increased desire by Senators to leave Washington, DC in order to do constituency work in their home state. So, we shouldn’t conclude that because filibusters and cloture are used more frequently today that the Senate is more susceptible to gridlock than it was 50 years ago. In fact, according to some political scientists, such as David Mayhew, legislative productivity has not decreased in this time. The Senate is no more prone to gridlock today than before.

2. That – as currently constituted – the Senate could today easily modify or eliminate the filibuster if a majority of 51 Senators wanted to. In other words, it is within Democrats’ power right now to end the filibuster, and there is nothing Republicans could do to stop them.

3. That Democrat senators do not eliminate the filibuster because it is one mechanism that protects regional and state interests. In short, it is an instrument of federalism, and an important safeguard for protecting one’s constituents, whether one is Republican or Democrat.

Judging by your email responses, many (most?) of you remain unconvinced. Several of you emailed articles by Ezra Klein, Paul Krugman and Tom Geoghegan, all of whom criticize the filibuster as a symbol of a broken Senate. And while it is true that their objections to the filibuster are largely rooted in the health care debate (and that none of them seemed to be objecting that much when Democrats were using the filibuster to block George W. Bush’s judicial nominees!), that doesn’t mean their arguments are without merit. As Emerson said, a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.

At the risk of revealing my tiny cognitive capacity, however, let me revisit the argument on behalf of the filibuster by extending my earlier comments. Critics argue that the filibuster is antimajoritarian; that is, it allows a minority of Senators to block proposals supported by large majorities. So, in the case of health care reform, we have a Democrat President who ran successfully on a promise to reform health care, and who was voted into office along with Democrat majorities in both the Senate and House, in part to fulfill this promise. A majority of the public, when polled, supported health care reform. And yet the ability of this majority party to fulfill a basic campaign promise is blocked by a minority of Republicans. This cannot be what the Framers intended when they established a representative democracy. As Bob Johnson quite cogently argues in an email to me, the reason we replaced the Articles of Confederation with the Constitution originally was to prevent individual states from blocking efforts to address national problems.

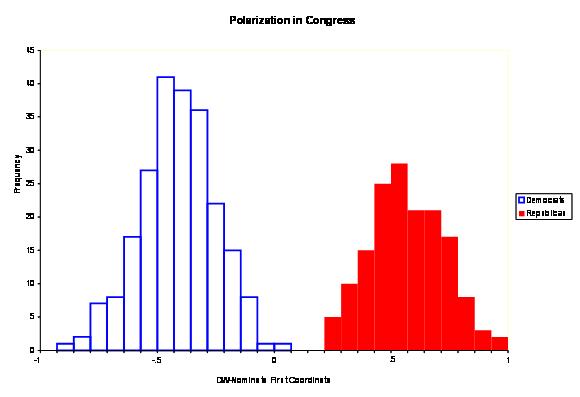

At first glance this looks like a persuasive argument. But let’s think about it in the context of health care and the current Congress. The mistake that opponents of the filibuster often make is to equate the sentiments of a majority of Senators with the views of a majority of the public. But we can see why they are not necessarily equivalent. Recall that the current Congress is the most polarized since the Civil War; as the figure below shows, there’s not much of a moderate middle, and no overlap between the two parties, ideologically speaking. (Blue lines signify Democrats, solid red are the Republicans. The X [bottom] axis measures ideology based on voting, and ranges from extreme liberal on the Left to extreme conservatie on the Right. The Y [left-hand] axis is the number of members of Congress falling within each space on the ideological continuum.)

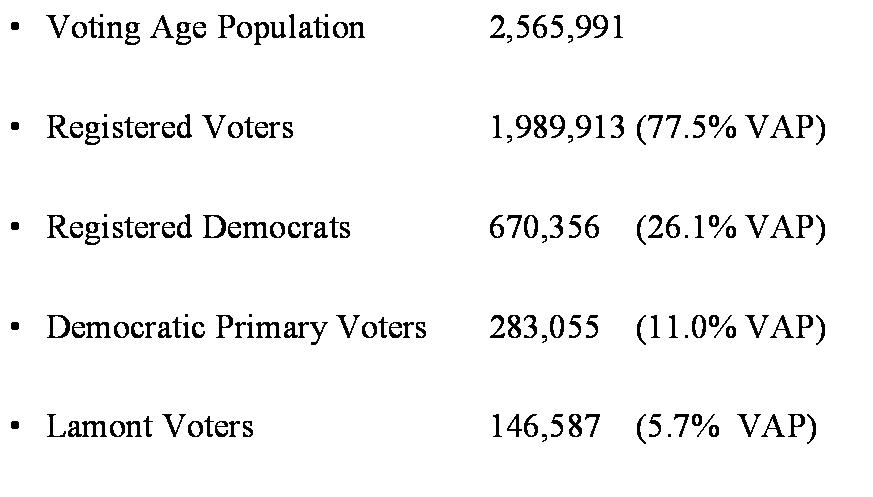

How did Congress get so polarized? One reason is that increasingly candidates must win a party primary in order to run in the general election. (Prior to the 1960’s party leaders often determined who would run on the party ticket.) Primaries, however, tend to attract a smaller number of voters who are not representative of the electorate at large; instead, they are often single-issue voters drawn from a party’s more extreme wings. For example, remember the 2006 Democratic primary in Connecticut in which antiwar activist Ned Lamont beat Joe Lieberman, largely on the strength of Lamont’s antiwar views? As this chart shows, Lamont won with the support of less than 6% of the voting age population in Connecticut.

How did Congress get so polarized? One reason is that increasingly candidates must win a party primary in order to run in the general election. (Prior to the 1960’s party leaders often determined who would run on the party ticket.) Primaries, however, tend to attract a smaller number of voters who are not representative of the electorate at large; instead, they are often single-issue voters drawn from a party’s more extreme wings. For example, remember the 2006 Democratic primary in Connecticut in which antiwar activist Ned Lamont beat Joe Lieberman, largely on the strength of Lamont’s antiwar views? As this chart shows, Lamont won with the support of less than 6% of the voting age population in Connecticut.

Had Lieberman dropped out rather than run as an independent, Lamont likely would have beaten the Republican candidate – one of a wave of Democrats elected into office in 2006 and 2008. Instead Lieberman ran in the general election and soundly beat Lamont, based in large part on support from more moderate voters (and not a few Republicans). Lamont’s case is unusual only in that Lieberman did not give up after losing the primary. Changes in how candidates are nominated increasingly mean that voters are forced to choose between two relatively extreme candidates in the general election, neither of whom – as we saw with Lamont – necessarily represents the policy views of the majority of constituents.

Had Lieberman dropped out rather than run as an independent, Lamont likely would have beaten the Republican candidate – one of a wave of Democrats elected into office in 2006 and 2008. Instead Lieberman ran in the general election and soundly beat Lamont, based in large part on support from more moderate voters (and not a few Republicans). Lamont’s case is unusual only in that Lieberman did not give up after losing the primary. Changes in how candidates are nominated increasingly mean that voters are forced to choose between two relatively extreme candidates in the general election, neither of whom – as we saw with Lamont – necessarily represents the policy views of the majority of constituents.

The result is a Congress in which neither party is necessarily very representative of the more moderate electorate. To see this graphically, imagine a bell curve distribution of voters based on ideology, with the most moderate middle in the center under the highest portion of the curve, signifying the greatest number of people. Now superimpose that on the Congressional polarization chart and you’ll get a sense of what I am arguing – Congress is least representative in the very middle.

Or, consider polling regarding health care. Americans support the idea of health care reform in the abstract. But, as happened in 1993, when asked to sign on to particular legislation, with all the tradeoffs reform inevitably entails, support for healthcare drops. We see this in the following table:

Indeed, the latest Pew survey suggests that health care reform is not even in the top five of issues of concern to Americans. And yet the health care legislation remains the focus of debate for members of Congress and policy activists on both sides, with Obama vowing to get some type of health care legislation passed.

You see my point. A majority of the Senate may favor the current health care bill – maybe even a near supermajority of 59 members. But that is not always the equivalent of the majority of the electorate because the moderate middle of voters is not always proportionally represented in the Senate.

So, why is this a defense of the filibuster? Recall that in 2005, Senate Democrats, although in the minority, used the filibuster to prevent George W. Bush’s judicial nominees from coming to a vote. Harry Reid defended the practice, arguing that Bush’s nominees were not in the political mainstream. Today, Republicans threaten to filibuster the Democratic health legislation, arguing that it goes too far Left and does not have the support of a majority of the public. Both sides may be right. That is, the majority party in the Senate in both instances may in fact have been pushing policy views, or nominees with judicial views, that were out of step with mainstream public opinion.

I do not disagree that the filibuster can be used by a minority of Senators to thwart the will of the majority of the Senate – a majority that represents the majority of voters. We saw that during the civil rights debates when a minority bloc of southern Senators prevented passage of civil rights legislation that most Americans supported. But what Geoghegan, Klein and Krugman ignore in their zeal to see health care legislation pass is that the filibuster can also be used to protect the moderate majority against more extremist policies too. As the Senate becomes increasingly polarized – it is now the most polarized since the Civil War – this latter function of the filibuster is, I argue, increasingly important.

In short, rather than serving only a strictly antimajoritarian purpose, the filibuster serves an additional crucial purpose in the modern Senate: it protects the majority interest by preventing either wing of the two parties from imposing its own more extremist views. Equally important, the increased use of the filibuster, and cloture votes, does not seem to have slowed legislative productivity, at least according to some political scientists. Important laws are still passed. We tend to lose sight of this in the current focus on the inability to pass health care legislation. Health care legislation may be stuck not because of minority opposition so much as due to flagging popular support.

For some of you, of course, catering to the views of the moderate middle is no virtue. I’m not necessarily defending a moderate perspective. I am arguing, however, that the usual case against the filibuster – that it is an antimajoritarian tool that prevents the Senate from fulfilling the will of the people – is not always true. Sometimes it protects the will of the people.

That’s the defense of the filibuster. Let the critics respond!

I’ll be on later tonight, live blogging the State of the Union address. Feel free to join in with commentary (“You Lie!”)