Stereotypes

What are stereotypes?

Stereotypes are oversimplified but widely-held beliefs about a group of people, often superimposed upon and used to subjugate a category or class of people.

What are ‘female’ stereotypes?

Women are uniquely subject to harmful stereotypes, which are simultaneously gendered, raced, and classed. Stereotypes exist for black women, gay women, Latina women, trans women, powerful women, women in STEM fields, women in the workplace, women in news and business magazines, the list goes on and on. These stereotypes are often replicated in media portrayals and consciously or unconsciously weaponized to reinforce patriarchal dominance.

How are stereotypes used in advertising?

Advertising is a unique venue of stereotype representation – it represents a conscious efforts on behalf of a corporation to capitalize on preexisting notions of identity, body image, and position in society. Marketing toward women presupposes certain stereotypes, which are mobilized to position women in need of products and processes to either correct or reinforce certain attributes (Caputi 314). As a purveyor of postfeminist media, the advertising industry constructs and reproduces often harmful and historically oppressive stereotypes of women, deploying these stereotypes as innate or even desirable.

From the (postfeminist) literature:

Popular stereotypes about women reinforce dangerous notions of gender, power, and capability. An implicit assumption of postfeminism is that “women’s status has improved,” drawing attention away from necessary social action and thus rewarding compliance with neoliberal, postfeminist norms (Anderson 13).

Stereotypes simultaneously denigrate and reward women (and the market-based behaviors that women enact by buying products). Using postfeminist logic, commodity culture is envisioned as a sphere in which women can purchase their own liberation. By purchasing products, women enact the liberation that has not been afforded to them by feminist movements; corporations become the main purveyors of freedom and liberation, and participation in capitalist consumption affords women the chance to conform to stereotypes invoked originally to denigrate them and exclude them from the public sphere.

Take, for example, wearing makeup. Makeup is a product that is, for the most part, associated with women; women wear makeup for a variety of reasons (stereotypically, to ‘express themselves,’ to conform to beauty standards, to look or feel ‘beautiful,’ and/or to erase blemishes which are deemed ‘ugly’). Purchasing and wearing makeup is portrayed in media as being an important part of a young woman’s coming-of-age process. Makeup commercials inundate young women, teaching them that wearing makeup is a necessary part of becoming a woman. Further analysis of makeup as a ‘necessary’ part of womanhood is needed. For example, makeup is expensive and inaccessible to many; lack of makeup in a variety of skin tones is just one example of how makeup companies have historically privileged certain (lighter) skin tones, and how lack of inclusive color schemes alienates women of color. Makeup is sold as a product to cover blemishes, since it is socially unacceptable to appear with acne, which hints at a larger (and more dangerous) social paradigm which demands young women appear perfect and without blemishes. Makeup is similarly inaccessible to many men, who are ostracized and mocked for wearing it, since makeup has become so deeply intertwined in Western concepts of gender and expression. Makeup is a product that should be scrutinized from a variety of feminist lenses, which I will continue to do below.

Stereotype #1: Women love (and need) makeup

This ad for No. 7 match made skin tone analysis – featuring Chimamanda Ngozi, renowned Nigerian author of the book-length essay “We Should All Be Feminists – exemplifies perfectly the postfeminist tension between stereotype and market behavior.

The ad begins: “our culture teaches us that if a woman wants to be taken seriously, then she’s not supposed to care too much about her appearance.” Ngozi explains that for awhile, she stopped wearing makeup and ditched her high heels (a dig at second-wave feminism) and “became a false version of myself,” as if one cannot fully be oneself unless she is wearing makeup or high heels. She claims that she eventually “woke up” and realized that she was wrong; she reclaimed the feminist stereotype of wanting to wear makeup and realized that she was only happy when she looked in the mirror to find a full face of makeup. The face that she chooses “to show the world” is one full made up, since she only regained her confidence after realizing that her confidence was contingent on makeup.

It is clear that this ad capitalizes on the postfeminist practice of offering market-based solutions to societal problems. The ad attempts to convince women that conforming to a stereotype (wearing makeup) will restore their self-confidence, which in the ad seems to have been removed by second-wave feminists who pushed back against the necessity of high heels and makeup for women. In this way, the ad is a postfeminist response to feminist activism, which is articulated in commodity form (an ad) and transformed into a means of producing neoliberal capital (Mukherjee and Banet-Weiser 2-3). Framing traditional expectations of femininity (i.e. wearing makeup) as empowering is dangerous, since it reinforces the notion that not conforming to stereotypes somehow degrades self-worth. Self-worth which is regulated by the free market refigures feminist societal critique into an “individualistic discourse, [which is] then deployed in a new guise. . . as a substitute for feminism” (Anderson 3). In addition to leading the consumer toward embracing feminine stereotypes, this ad ignores the social ramifications of not wearing makeup.

That the company chose Chimamanda Ngozi as a spokeswoman speaks to purposeful positioning within postfeminist thought. Ngozi – a prominent self-proclaimed feminist, though not without critique – is claiming to find empowerment through embracing feminist stereotypes. A feminist is pushing back against a feminist critique of the beauty industry. This is as powerful a marketing strategy as it is deceptive. Her presence negates legitimate feminist critique of misogynistic beauty practices, standards, and expectations that operate in tandem with neoliberal co-optation of feminist activism. Her positioning as a feminist conforming to postfeminist expectations confirms the widespread grasp that postfeminism has on media and the market.

Stereotype #2: Women love (and apparently hoard) shoes

Women love shoes – or so goes the stereotype. Women have an uncontrollable need to shop, and shoes are no exception. Other commercials, such as this ad from Heineken comparing women’s shoe obsession with men’s love for beer, show women drooling over shoes or, colloquially, shopping until they drop.

This ad takes for granted the fact that women obsess over shoes, beginning with a defensive “I’m not a hoarder!” The whole ad is 15 seconds long, consisting of Mindy Kaling defending her love of shoes by saying: “I’m a multifaceted women with nuance and complexity, and I need choices. Beautiful choices,” before plugging DSW’s multiplicity of choices of designer shoe brands.

https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=1079517238903025

That the ad so strikingly embraces the ‘shopaholic’ stereotype speaks to its sexist, yet postfeminist, stance. The irony of Kaling claiming she is “not a hoarder” is evident, as she is positioned as an uncontrollable, almost pathological, spender, overflowing with consumer products to exemplify her shopaholic tendencies. The ad simultaneously glorifies the aforementioned feminine stereotype by providing “opportunity for narcissistic indulgence” and “deal[ing] a blow to her narcissism,” trivializing the fact that gendered assumptions about spending feed into larger assumptions about female behavior – that women rack up debt, spend their husband’s hard-earned money, obsess over material objects, etc (Jeffreys 8). The ad employs rhetoric that gives women “agency, choice, and empowerment” in the form of social capital, which pushes back against negatively-coded feminist critiques of capitalism and gendered stereotypes (Jeffreys 5; Mukherjee and Banet-Weiser 3). Rather than co-opting feminist symbols through commodity feminism, this ad appeals to women to embrace traditional modes of femininity in critique of feminist ideals (Mukherjee and Banet-Weiser 46-47).

Using irony to critique stereotypes

The practice of capitalizing on feminine stereotypes in advertising is widespread and often insidious, as exemplified by the aforementioned ads. One instagram account, @feministads, satirizes and spoofs ads that are misogynistic, postfeminist, and/or those that embrace feminine stereotypes. (Note: all of the ads are fabricated by the artist to elicit social commentary on the advertising industry).

Take, for example, these artworks:

It upends the stereotype that women belong in the kitchen. This piece is one of many that mock ‘feminine’ stereotypes.

“Hands-off cleaning” here applies to the 1950’s-esque idea that men should play no active role in keeping a house clean. (That this idea still exists and that women still comprise the majority of homemakers and the responsibility to cleaning house falls on women is not addressed).

Or this ad, which repurposes the feminine stereotype that women require relaxation or are emotionally ‘strung-up’ or ‘too emotional.’ This ad fits among works of literature like “The Yellow Wallpaper” or even the recent “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” that broach the quasi-medical panic about hysteria and over-active female minds.

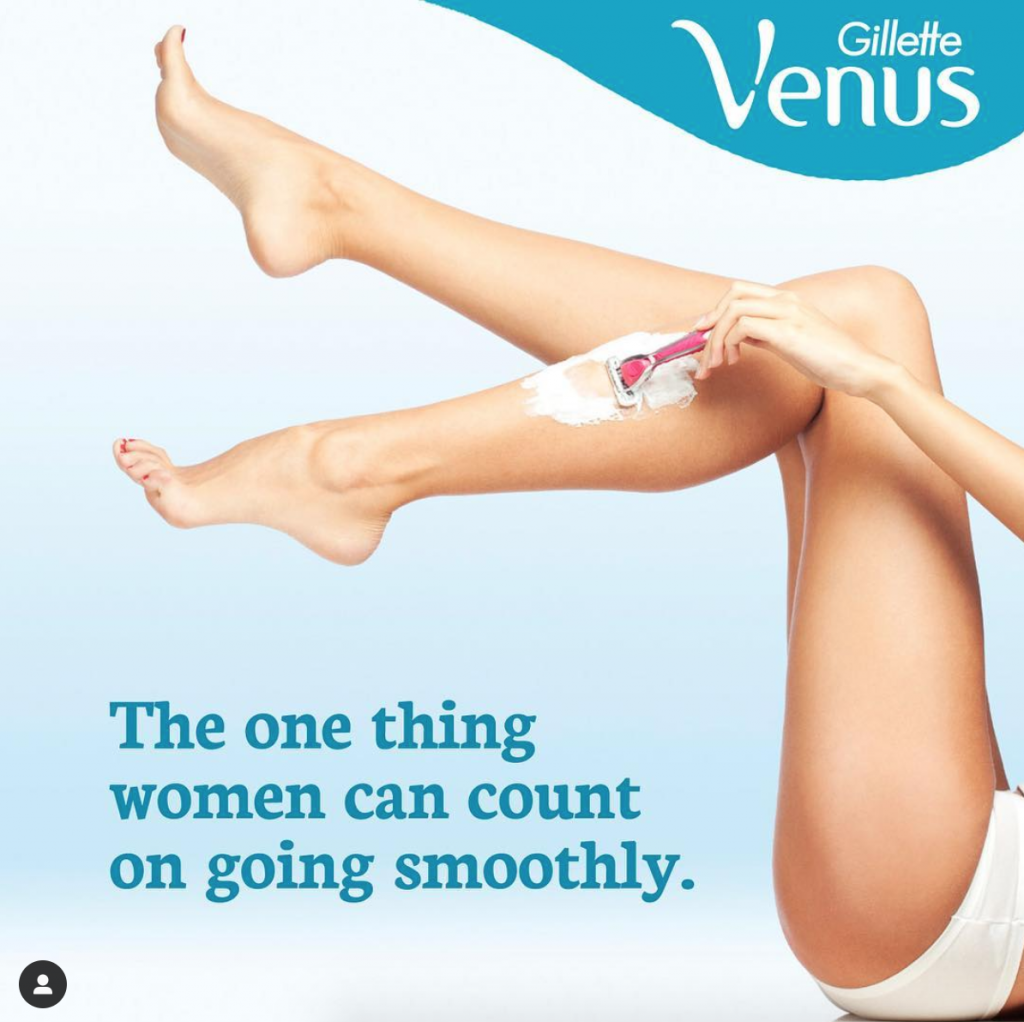

This ad approaches stereotypes differently, positioning the woman as unquestionably needing to shave her leg hair and thus conforming to misogynistic Western expectations of beauty and grooming. The woman pictured here in thin and light-skinned, further conforming to Western notions of ‘beauty.’ The satire in this ad is more subtle, mocking the fact that women’s lives are deeply politicized and often turbulent; shaving, then, is a refuge from instability. A woman can always count on her razor to get the job done, and a woman dares not question to misogynistic assumptions about attaining ‘beauty’ and stigmatization of body hair.

Bibliography

Anderson, Kristin J. Modern Misogyny: Anti-Feminism in a Post-Feminist Era. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Caputi, Jane. “The Pornography of Everyday Life,” in Gail Dines and Jean Humez, ed., Gender, Race, and Class in Media, 3rd edition (2011). 311-320.

Jeffreys, Sheila. Beauty and Misogyny: Harmful Cultural Practices in the West (Routledge, 2005): excerpt.

Mukherjee, Roopali, and Sarah Banet-Weiser. Commodity Activism : Cultural Resistance in Neoliberal Times. New York University Press, 2012.