Andrew Wolfley

Positionality Statement:

As a current sophomore and international and global studies and geography major at Middlebury College, I have always had a fascination with the ways in which the food that we eat is processed, transported, and delivered to our kitchen tables. Growing up in a multicultural home with a Colombian mother and an American father, there was always an importance given to the freshness of the food that we ate at home. These eating habits have continued throughout by life and have come to shape the way in which I value the food that I eat and hence the way that I interact with the local and global food systems that surround me.

With the recent defeat of Proposition 37 in the state of California, that if passed would have deemed that “any food offered for retail sale in California is misbranded if it is or may have been entirely or partially produced with genetic engineering[1] and the fact not disclosed” (The California Right to Act, 2012) suggested that the average consumer was no longer interested in knowing how their food is produced or processed within the American food system. The infamous political influence of electoral propositions in California meant that Proposition 37 would not have only created a GE labeling zone within California but it would have paved the way for other states to do the same and hence drastically transform the American system of mass food production. Although the US$370 million dollar anti-Prop. 37[2] campaign that was led by agro-giants Monsanto and DuPont come out on top, this political victory did little to explain why, according to multiple surveys and polls almost 90% of Americans were in favor of GE labeling.[3] In the following paper I attempted to deconstruct the labeling discourse through a framework of political ecology to further understand the parallel rhetorical frameworks that have come to construct this intensely polarized debate.

The labeling of genetically engineered crops and foods is the combination of distinct cultural, political, and economic scales that are consistently interacting with one another. The concern made by activist groups, such as Greenpeace for the need to label food products that are derivatives of GE technology cannot be dismissed as solely a matter of current political, corporate, and social clashes but rather of responsibility and therefore morality (Kirby, 2, 2001). Innovations in seed production and quality have been an essential part of the American farming system since the colonization of the United States. The native plants of North America consisted of only sunflowers, blueberries, cranberries, and Jerusalem artichokes. A clearly inadequate food supply for the establishment of a permanent European colony in the New World (Kloppenberg, 51, 1988). The need to diversify the food system and produce new food sources lead many farmers and colonizers to commence a global germplasm exchange program that consistently introduced new and exotic varieties of seeds into the farming practices.

The genetic modification of seeds has been an essential part of American agriculture since its foundations. The importance and ratifications that these historical farming practices have had in terms of the labeling discourse is that they have set up the progression of the agro-industrial system within the United States that depends heavily on the use of genetically engineered technology. For many biotechnology companies like, Monsanto the historical context of the American farming system is used to support the “naturally” deemed progression of independent farmers into industrial employees via the use of GE seeds (Stone, 2002, 612). For many of these biotechnology companies the commodification of the seed is just the next step in dismantling the limits of nature. As boasted by Monsanto itself “all life is chemical” meaning that a gene is just a gene and it is still inherently a part of nature, even if it was used within a process of genetic engineering (Kloppenburg, 193, 1988).

With the rapid adoption of GE technology in the United States during the 1990’s, no new regulatory bodies were created to control the use or production of GE crops and foods (Guehlstrof et. al, 334 2005). The labeling of foods evidently becomes a response to the lack of regulation that agro-industry was experiencing (Guthman, 135, 2003). The knowledge structures that are produced inherently because of the voluntary labeling of organic food products during the 1980s, for example led to the formation of what Dimaggio defines as a cultural schemata of perception (269,1997). This cultural phenomena refers to the assumptions that are made by a community about a products characteristics and relationship of such products when provided with incomplete information (Schurman et al, 165, 2009). The deregulation of the American agro-industrial sector led more and more people to rely on labels to know what was in the food that they were consuming, a cultural perception that is clearly expressed within the current labeling discourse.

However, it is important to note that there is large public trust among the American public when it comes to federal regulatory agencies, such as the Food and Drug Administration, also known as the FDA (Schurman et al, 185, 2009). The scientific objectivity that soon became the backbone of the greater confidence in the FDA and biotechnology sector among the American public was spurred by an ideology that all the claims made by “agro-giants” and federal agencies were made within “sound science” (Guehlstorf et al. 328, 2005). The practice of “sound science” reflected by the FDA has deemed GE products substantially equivalent to their conventional counterparts meaning that there is no need for a “new” labeling system. This method of substantial equivalence adds to the cultural perception that labeling of GE products is not necessary for the food that we eat has been made for us through a strict, safe, and scientific regulatory process where there is no difference between GE crops and organically produced food products (Herrick, 289, 2009).

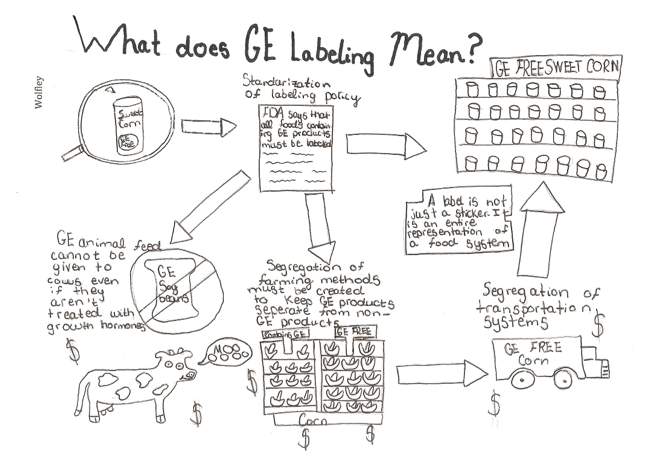

The evident contrast in the culture perceptions of the GE labeling debate pushed the crops and foods that are produced by these technologies into becoming goods in which the quality of the product could not be determined by the consumer (Gruère et al. 1473, 2008). In response to these uncertainties some producers utilized voluntary labeling in an attempt to correct the presence of imperfect information and legitimize the value of their product (Caswell et al. 1250, 1996). This superficial role that has come to define the practice of labeling within the large political debate in the US is a reflection of the cultural perceptions tied to the labeling discourse itself. Very few Americans substantial know or understand the consequential effects that labeling could have in transforming the American food system, a point that is clarified with the visualization located at the end of this paper.

The regulations that have been produced by the FDA, combined with the social dependency of the consumer market to rely on labels for information has transformed the legality of labeling into a socially determined interpretation of scientific data (Klintman, 80, 2002). The partial knowledge that has come to construct the discourse of labeling is not only an interpretation of the cultural perceptions that have come to define food labeling in the US but also the rapid and extreme polarization of the labeling debate through the politicization of GE seeds. The attempts made by anti and pro GE groups to educate the American public about bioengineered crops and foods via the discourse of labeling has a created a paradigm in which the unique cultural perceptions of labeling are being pinned against once another (Haniotis, 171, 2001). The binary that has been created within the labeling debate must be deconstructed to further illuminate the gap that has been created between public demands and government responses within the American culture of acceptance. The current discourse that has created the blueprint for the labeling debate must be re-interpreted to outline the fine line that exists between enabling innovation, while simultaneously ensuring the safety of the American public (Herrick, 290, 2004).

In conclusion, the American culture of GE acceptance and the subsequent debate on the labeling of bioengineered crops and foods has a unique historical and cultural context that has come to define this political framework. In my attempt to deconstruct the labeling discourse I demonstrated the interrelation between the multidimensional natures of labeling. By utilizing political ecology as a framework of analysis a clearer comprehension of the labeling debate is created that is not limited to solely a political lens. The powerful influence of cultural perceptions and historical context is embedded within the labeling of all foods in the United States and they should be interpreted as essential holistic lenses of analysis. The partial knowledge that has been disseminated through the anti/pro bioengineering binary within the American political sphere must be deconstructed to improve the comprehension of the complex sociopolitical, economic, and agricultural nature of the debate. The amplified lens of analysis that is offered by this paper provides an essential tool for understanding how cultural perceptions have come to be fundamental in shaping the dynamics of not only the labeling of GE crops and foods but the entirety of the biotechnology movement and sector.

Bibliography:

American Medical Association Council on Scientific Affairs. 2012. “CSAPH Report 2-A-12: Labeling of Bioengineered Foods”. Available at http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/csaph/a12-csaph2-bioengineeredfoods.pdf. Accessed 05/23/12.

Caswell, J. and Mojduszka, E. 1996. “Using Information Labelling to Influence the Market for Quality in Food Products. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 78 (5). Pp. 1248-1253.

DiMaggio, P. 1997. “Culture and Cognition” Annual Review of Sociology. 23 (1). Pp. 263-87.

Frank, D and Medina, D. 2012. “Who’s Funding Prop 37, Labeling for Genetically Engineered Foods” Available at: http://www.kcet.org/news/ballotbrief/elections2012/propositions/prop-37-funding-genetically-engineered-food.html. Accessed 05/22/12.

Gruère, G. Colin, C. and Hossein, F. 2008. “What Labelling Polcy for Consumer Choice? The Case of Genetically Modified Food in Canada and Europe. The Canadian Journal of Economics. 41 (4). Pp. 1472-1497.

This article utilized an economic lens of analysis to explore the diverging opinions amongst customers when interacting with GE labeling. The article proved a well-versed explanation as to how labels are perceived as quality markers by consumers. The article also explored how labeling can become a product of consumer habits under some circumstances.

Guehlstorf, N. and Hallstrom, L. 2005. “The role of culture in risk regulations: a comparative case study of genetically modified corn in the United States of America and European Union.” Environmental Science & Policy. 8 (1). Pp. 327-342.

The article written by Guehlstorf and Hallstrom provide a unique and deep anthropological and cultural explanation as to why American consumers have relied so heavily on regulatory bodies to determine the safety of their food. It also incorporated a cultural analysis of risk assumption that greatly added to the understanding of cultural perceptions within the paper.

Guntham, J. 2003. “5: Eating Risk: The Politics of Labeling Genetically Engineered Foods” Engineering Trouble. University of California Press: Berkeley, CA. Pp. 130-151.

Herrick, C. 2005. “Culture of GM: discourses of risk and labeling of GMOs in the UK and EU.” Royal Geographic Society. 37 (3). Pp. 286-294.

This article explored the contention that has set the stage for the labeling discourse. It provided an in-depth understanding as to why American consumers have not actively rejected or supported GE labeling by utilizing a cultural lens of analysis.

Haniotis, T. 2001. “The economics of agricultural biotechnology: differences and similarities in the EU and UK”. Genetically modified organisms in agriculture: economics and politics. Academic Press: San Diego, CA. Pp. 171-179.

Klintman, M. 2002. “The Genetically Modified (GM) Food Labelling Controversy: Ideological and Epistemic Crossovers”. Social Studies of Science. 32 (1). Pp. 71-91.

This article examined the conflicting arguments surrounding the labeling of GE crops and foods made across social coalitions, the corporate sectors, and policy-making. It laid out the disparities that exist between policy and public opinion in the United States. It demonstrated the limited analysis that is provided by utilizing just a political lens of analysis to understand the labeling of genetically engineered products.

Kloppenburg, JR. Jr. 1988. “The Genetic Foundation of American Agriculture” and “ Outdoing evolution: biotechnology, botony, and business”. First the Seed: The Political Economy of Plant Biotechnology. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK. Pp. 50-241.

Schurman, R. and Munro, W. 2009. “A Cultural Economy Approach to Understanding the Efficacy of Two Anti-Genetic Engineering Movements”. American Journal of Sociology. 115 (1). Pp. 155-202.

This was the most influential source of research that was used within the paper. It provided an extremely well written, cultural approach to the current labeling debate. The article by Schurman and Munro articulated how the political and economic spheres of the American landscape are culturally constructed. It broaden the scope of analysis for this paper by providing the inclusion of a historical context of agricultural production in the United States, as well as the food labeling process within the country.

Stone, G.D. 2002. “Both Sides Now: Fallacies in the Genetic-Modification Wars, Implications for Developing Countries, and Anthropological Perspective”. Current Anthropology. Vol. 43 (4). Pp. 611-630.

Yes on 37 For the Right to Know if Your Food Has Been Genetically Engineered. 2012. “The California Right to Know Genetically Engineered Food Act. Available at: http://www.carighttoknow.org/read_the_initiative. Accessed 05/25/13.

[1] According to the American Medical Association (AMA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) since plants that have been genetically enhanced through conventional breeding techniques, such as cross pollination can also be considered genetically modified, the terms genetically engineered or bioengineered will be used throughout this paper to describe plants and/or animals that have been scientifically enhanced with the introduction of distinct genetic traits via direct gene transfer.

[2] Donation amounts provided by: http://www.kcet.org/news/ballotbrief/elections2012/propositions/prop-37-funding-genetically-engineered-food.html

[3] According to various polls done by MSNBC, the Washington Post, ABC News, and the Consumers Union around 93% support the labeling of genetically engineered crops and foods.