It’s not your imagination, the leaves are turning early this year. The reason will seem a little odd, but an understanding of a tree’s relation to time helps.

I feel for scientists that have trouble explaining the concept of time. We are lineal creatures, stuck watching time pass from one year to the next. As a horticulturist, my year goes from spring to spring. But anthropologists measure civilizations in centuries, not our ordinary years. How about geologists, counting back years by the billions. Most impressive, let’s talk about Astronomy. A light year-the time and distance it takes for a photon of light to travel. It’s called the speed of light for a reason.

Tree time moves differently. Trees do everything slowly-germinate, grow, mature, reproduce, even die. Some varieties live well within one of our short lifetimes, while others will live for generations. Time moves in fits and starts for a tree, on yearly cycles familiar to those in Agriculture. But they aren’t exactly lineal.

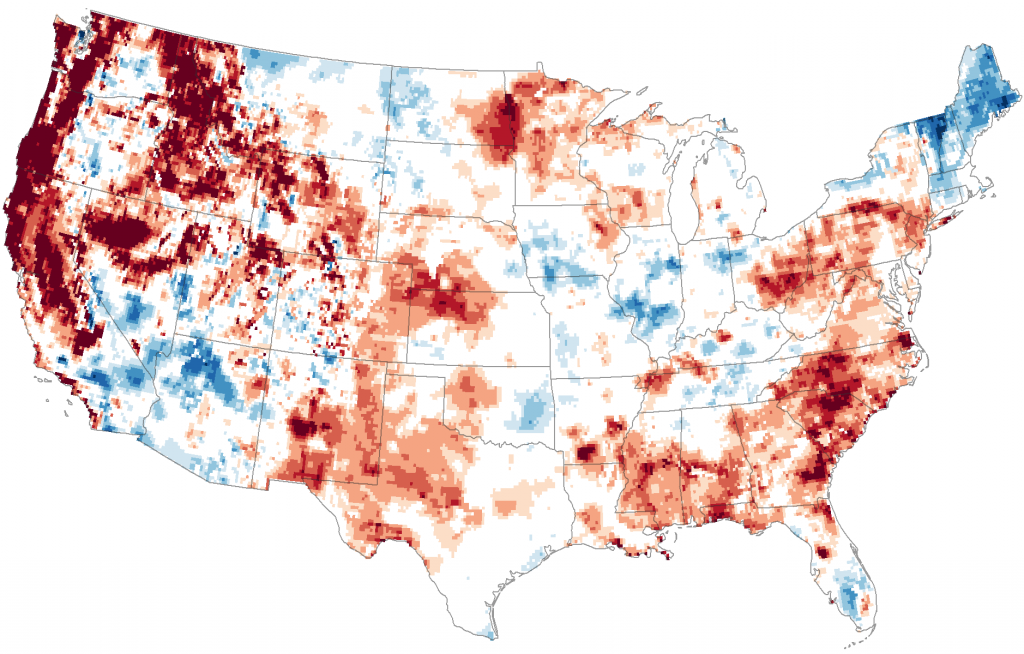

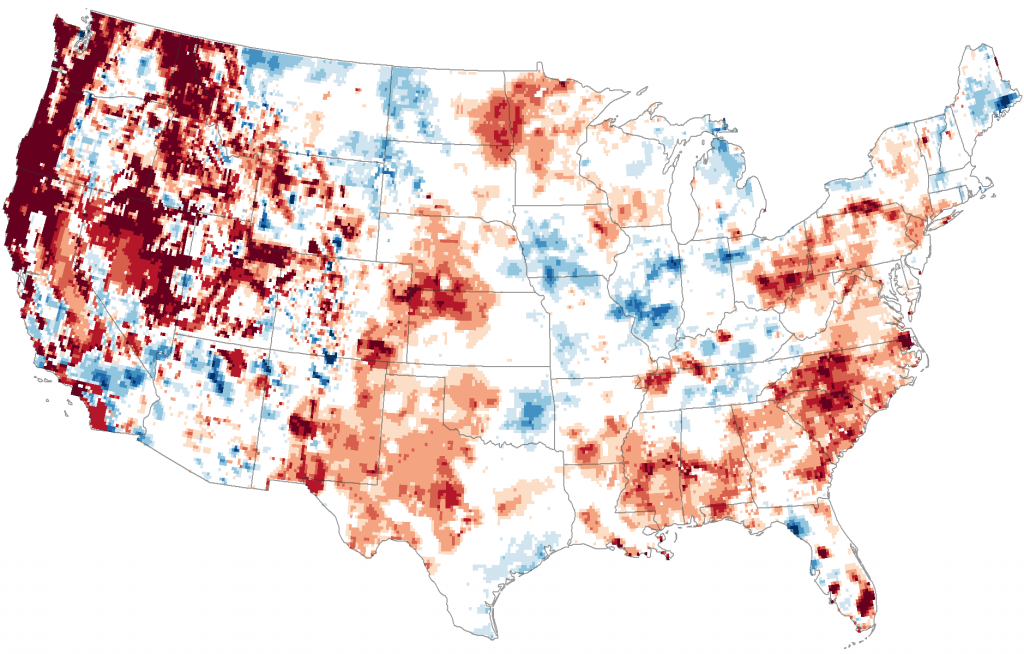

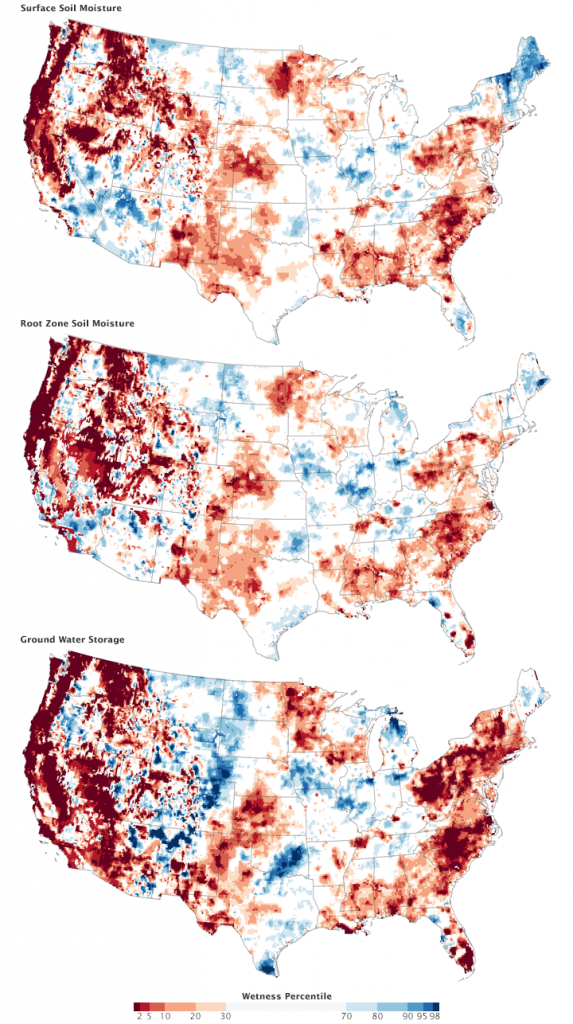

Remember last year? It was a growing season in a bitter drought, with no rain for most of the spring, all of summer, not breaking until late in the fall. It was hot, dry, and overall not very pleasant. I use our annual flowers we plant as a barometer, and the ones we planted around campus languished in the heat, and with the exception of some petunias none ever really amounted to much.

Our tree canopy looked OK though, and we had a nice fall. But this year, not so much. Maples are turning early, losing their already smaller than normal leaves about 4 weeks too soon. Oaks have been thin all year, with many dead twigs and branches. But it was a great growing season this year, with all flowers blooming non-stop since commencement. But not in tree time.

August 30

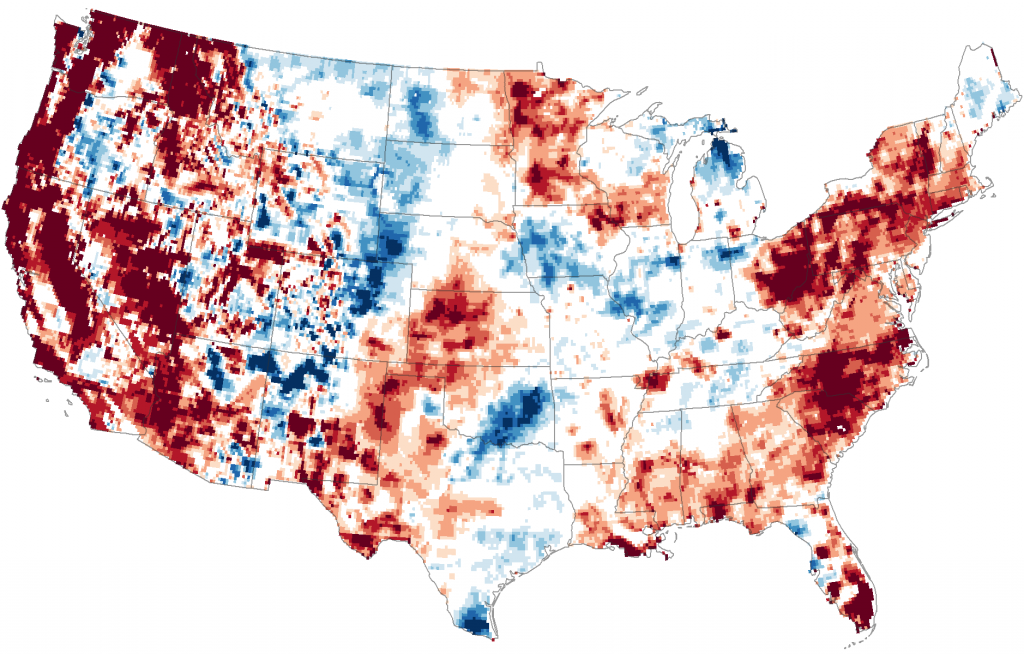

Trees are about a year off, marking time in their own way. They leaf out and grow all season, but reach back to the previous year’s sugars and energy stored from the prior growing season. Last year’s food is this years energy. So the drought last year certainly affected the growth of trees, but on tree time it doesn’t show up until this year. Weakened roots and inadequate resources in twigs and stems are stunting growth this year, and trees are wearing out and starting to turn early. Trees live a dual year, growing in the previous year while stockpiling for the next.

September 18

Ordinarily in the early fall there are always a couple of trees starting to turn, and the easy answer is that they are weakened, stressed trees, our canary in the coal mine showing us underlying problems we might not have seen. Usually the Black maples east of Old Chapel turn fall color early, a problem of not only age but poor soil and compaction from living in a college quad for 200 years. This year, though, it is many, many trees. Primarily sugar maples, and mostly middle-aged trees, I’d guess 40-75 years old. In tree time for a maple you can think of them as 30-year olds facing a mid-life crisis with all the associated baggage. Primarily we’ve seen trees turning this year as ones in poor soil, either on ledge, or heavy clay. Above my house on Snake Mountain I see the canopy turning color, the relatively young forest showing it’s stress.

Younger, less mature trees are probably more in balance, and also flaunt vigorous and resilient root systems, while old, mature veterans had the massive underground roots to weather the (lack of) storms. Neither are showing the stress or are turning early.

It’s too soon to say what the fall will bring for color, but I’d sure like to see a little more rain soon, and a break in this mini heat spell we’re having. I do predict an early season, though, maybe longer if the oaks in the lower elevations can hang in there.

You must be logged in to post a comment.