The Davis Family Library has highlighted a variety of groups and discourses through displays over the last 10 months including racial/ethnic minorities, the LGBTQ+ community, people with disabilities and themes of access and universal design. Take the opportunity now to critically examine whiteness as an identity and system of privilege. Visit the Davis Family Library lobby December 1st through the 17th to see works that highlight this topic. Also, listen to Dr. Laurie Essig and Dr. Daniel Silva interrogate whiteness as a social and historical construct via StoryCorps with transcript found at On Whiteness with Laurie Essig, Daniel Silva, Katrina Spencer. Use the whiteness glossary to enhance your vocabulary surrounding this topic. All underlined terms and more appear in the glossary.

Listen to the “On Whiteness” interview here.

From left to right, Middlebury College Portuguese Professor Dr. Daniel Silva, Literatures & Cultures Librarian Katrina Spencer and Gender, Sexuality and Feminist Studies Professor Dr. Laurie Essig participate in an interview in which they address the topic of whiteness. Listen to it via StoryCorps.

Contributors’ Names; Hometowns; Roles on Campus; Times At Midd:

AM: Addie Mahdavi; Newfane, Vermont; American Studies Major— Part of Middlebury Anarchist Coalition; Women’s Ultimate Frisbee. I’m entering my fourth year at Middlebury.

AF: Amy Frazier; Memphis, Tennessee; Film & Media Librarian; 2 years.

KS: Katrina Spencer; Los Angeles, California; Literatures and Cultures Librarian; 10 months.

LE: Laurie Essig; from a lot of places, mostly NYC; Professor of Gender, Sexuality & Feminist Studies; 11 years

Do you identify as white?

AM: I do identify as white. My relationship with whiteness can feel complicated by my also being Iranian (and vice versa), but I am read and I move through the world as a white person, so that’s how I identify racially.

AF: It’s just an acknowledgement of reality: I’m so, so white. My family is all WASPs (White Anglo-Saxon Protestants) on one side, and Scots-Irish hillbillies on the other. Being from the South adds a flavor, if you will, to my whiteness, but not always a welcome one.

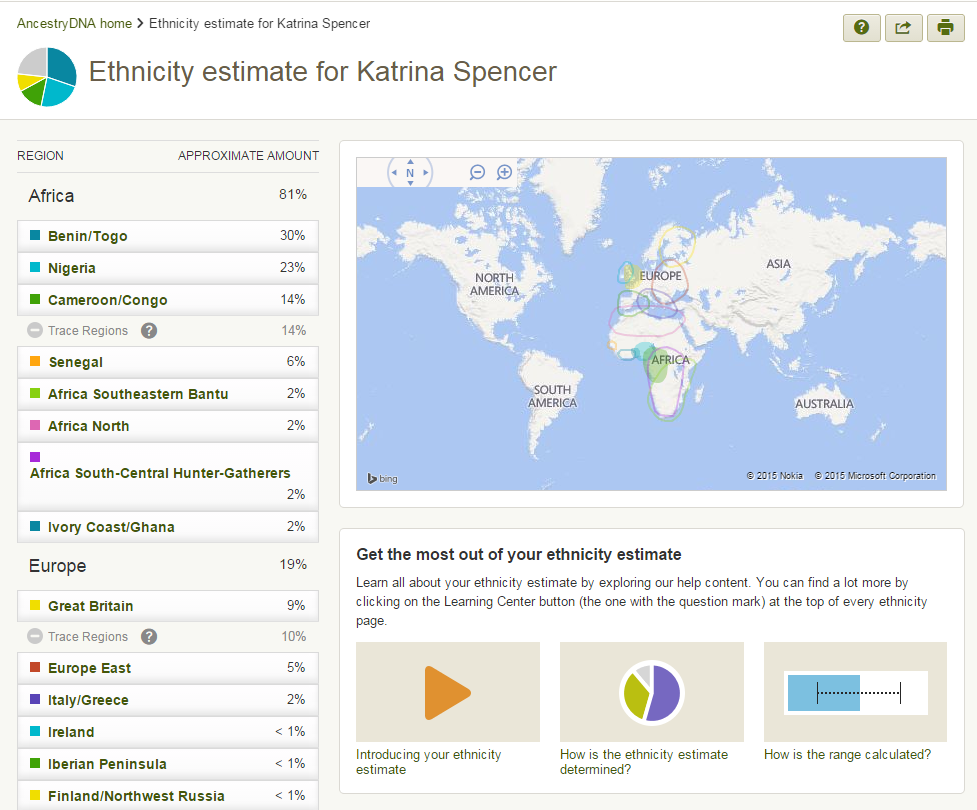

A screenshot of Katrina Spencer’s ancestry.com results revealing that 81% of her DNA is shared with groups originating in Africa and 19% of her DNA is shared with groups in Europe, originally posted on Glocal Notes, a blog from the International and Area Studies Library at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

KS: No, I don’t, but, as I was once told, my skin didn’t get to be this color on its own. That is, there is some history of miscegenation in my genes. When I had my DNA evaluated, it was revealed that 19% of my ancestry is European. So, no and still no. But maybe a little?

LE: I am white. Whiteness is written onto my body, but it is an unstable whiteness as a Jew. Jews became white in the US after World War II, but that whiteness has always been a not fully completed project as we can see from the present rise in anti-Semitic groups and politics. Also, in Russia- where my family is from and where I have lived a lot- Jewish is a different racial category than (white) Russian.

What is whiteness?

AM: Whiteness is a racial category that changes over time to include and exclude different ethnic groups based on relationships of power. There is no discernible culture or shared set of features that all white people have in common, aside from the shared experience of holding race-based power and privilege.

AF: “White” is what we (white people) inadvertently made ourselves when we decided that color was an acceptable basis upon which to oppress and subjugate other human beings. If they were black and brown, then we were white, even if we didn’t intend to define ourselves in the process of dehumanizing others. And I think whiteness is the baggage — the habits, the assumptions, the presumptions and privileges — that we acquired when we separated ourselves from other people. In more popular terms, I think whiteness encompasses whatever is easy, comfortable, accessible, and unchallenging for white people.

KS: “White” is frequently an “unmarked” identifier, mistakenly understood to be the default category for “authentic American” and synonymous with “standard,” “neutral,” “morally right,” “upstanding,” “correct,” true,” “sincere,” “altruistic,” “wholesome,” “pure,” etc. In our society, too often, “white,” as a noun, is equivalent to “person,” which renders non-whites something else.

Whiteness, on the other hand, is quite closely correlated to the multiple ways in which the dominant culture protects, promotes the interests of, perpetuates and preserves the privileged status and wealth of the [frequently] lightly complected descendants of Europeans and those who “pass.” (Those who “pass” may trace their ethnic and racial origins to groups outside of Europe but may share enough physical features that resemble whites that, to some degree, they are integrated into this group, are not perceived as imminent threats, and benefit from this acceptance.)

In essence, whiteness encompasses how our societies receive and respond to people identified as “white.” It is important to note that the category has been mutable for centuries and that its impact and power are transnational. Through art, media, economic relationships, and the legacies of colonialism, this system of privilege has been spread across the globe. It is not uniquely [North] American.

A still image from the 1939 cinematic production Gone With the Wind. Actress Vivien Leigh (left) and Hattie McDaniel (right) are featured in their roles, respectively, as Scarlett O’Hara and Mammy. Their characterizations are race-based, Scarlett being prim, cultured and privileged; Mammy being wide, uneducated and subservient. Image Source: Creative Commons

LE: Whiteness is a historical project, one that began in earnest in the U.S. after the Civil War. When racial hierarchies were unmoored from slavery, they were reestablished, as W.E.B. Dubois tells us, through “the Color Line.” Jim Crow policies in the South, but also federal immigration policies, incarceration of “enemies” like Japanese Americans, and the denial of employment and educational opportunities were all linked to this Color Line. Who achieved “whiteness” and who did not in the past 150 years or so is not set in stone, but an ongoing battle.

How does whiteness manifest itself at Midd?

AM: In a lot of ways, but maybe most clearly in the assumptions made about what people need and don’t need in order to thrive here. Socially, academically, economically, and culturally, Middlebury is definitely designed to be a place where whiteness and white people can flourish, which doesn’t necessarily mean we will, but we are certainly better situated to do so than people of color.

AF: I find it genuinely difficult to address this question articulately, because the degree to which whiteness is manifest here is… kind of overwhelming. I mean, how does water manifest itself in the ocean? Look down; you’re soaking in it. One of the more pernicious habits we still frequently perform is to regard a “typical” member of our community as white. What does a Vermonter look like? What does a Middlebury student look like? The first face that pops into my head is still a white one. Demographically, that’s probably not so far from the reality, but the assumption behind it can lead us to dismiss, discount or even just overlook the perspectives of people of color as those of “other people.” They’re not other people; they’re us.

Cover art from Sara Ahmed’s book Living a Feminist Life

LE: Sara Ahmed tells us that in historically white educational institutions like Midd, the very space itself is oriented around whiteness. To enter this space as a non–white body is to be immediately hypervisible and, in many ways, suspect of not belonging. That certainly happens at Middlebury. It has the look and the feel of a gated community- golf course, tennis club, the “rural,” even the use of an “e” at the end of the Grille to mark it as “olde English”– make this a space where bodies that have primarily existed in white spaces are “comfortable” and also unmarked/invisible.

KS: I was reading a piece covering Dr. Angela Rose Black that features a question she regularly poses: “Who gets to be well?” and it’s a relevant one for our campus and “community.” Who gets to to see himself/herself/themselves regularly reflected in our curriculum, faculty and staff? Who gets multiple and diverse opportunities to pick from a sea of mentors they trust? Who gets to be inspired by high-ranking Middlebury personnel who look like them? Who gets access to high quality mental healthcare provided by people who intimately know of their cultural experiences? Who consistently has their presence on this campus accepted, lauded and taken as a given? Who can attend a lecture by a controversial figure whose writings imply a racial hierarchy, enter it with a neutral mindset, and walk away utterly unscathed by its implications? Who is welcome to make serious mistakes and be excused for them? If we honestly answer these questions then we can see the ways in which whiteness manifests itself here in Middlebury.

In what ways can whiteness be problematic?

AM: When whiteness is equated with normalcy, as it often is (e.g. in the language of referring to people of color as “minorities”), it positions all other races as deviant, and leads to marginalization and invisibility or hypervisibility. Because white colonizers, scientists, politicians, theorists, etc. have violently maintained power for so long, whiteness is centered as the dominant cultural narrative in the United States and as a result institutions like Middlebury, which should be accessible to everyone, are designed only to meet the needs of white people.

AF: If “whiteness” is a product of our dehumanizing of other people, it has also served to partially separate and disconnect white people from most of the rest of humanity. This weakens us as individuals and as a society; it has led us to do things and construct systems that make us, in turn, less human.

A 31 July 2014 screenshot from Twitter user @CraigSJ‘s feed featuring white singer Katy Perry with an ancient Egyptian hairstyle and bejeweled teeth (at left), in a kimono (at top right) and cornrows (at bottom right).

KS: A large debate over the last few years addresses cultural appropriation. When white people or other groups tap into a tradition that is distinctly not theirs and profit from it while frequently and simultaneously demonizing the originators of said tradition and/or divorcing the originators from their cultural product, we encounter serious problems. We see this in music, fashion, art, culinary practice and more. As the many think pieces suggest about the Internet suggest, white people twerking in cornrows while wearing “grills” is seen as edgy, “adult” and alluring; black people twerking in cornrows while wearing grills is seen as low-class, shameful and hypersexual.

LE: Hegemonic whiteness is problematic because of a long history of being used to create social hierarchies- not just against people of color, but against sexual “degenerates” and “white trash” (poor whites). Whiteness is also problematic because, like gender, it can operate as “commonsense” and “real,” when in fact it is historically specific and culturally determined. But perhaps this is also the contradiction that can be exploited within whiteness- the space where hegemonic whiteness can begin to fall apart.

What motivated you to be a part of this display?

AM: One of the reasons it’s easy to center whiteness as the norm is because we seldom engage with it as a phenomenon worthy of critical examination. When we question the development, maintenance, and impacts of whiteness, we come closer to de-centering it from seeming “natural” in the American social landscape and create space to value and support different racial and ethnic identities and experiences.

AF: “When all you’ve ever known is privilege, equality feels like oppression.” We see this in aggressive, destructive action all around us, and the fundamental lack of self-awareness and perspective in large swaths of white society is fuel on the fire. And as a white person, I think I have two absolute obligations: to be proactive in working to combat my own gaps in awareness and perspective; and to be open, responsive, and frank in conversation with others. So things like this are an opportunity, even in a small way, to challenge white supremacy from the white side.

KS: If you come to the Davis Family Library regularly, where I am the only black employee, you’ll know that with the help of many students, staff, and faculty, I’ve been helping to develop displays about various cultural identities since Spring 2017. When I started, I had no intention of critically examining whiteness. But after Jonathan Miller Lane’s Rifelj lecture and call to action in September, I felt motivated to do so. Essentially, if we talk about blackness, brownness, yellowness and redness, we must establish opportunities to talk about whiteness as well. They all exist in a system together. It doesn’t make sense to talk about four of them and not the fifth. We must position our lens of scrutiny and inquiry on the dominant culture, too.

LE: All of the courses I lead are situated in critical race theory and one of them, White People, focuses specifically on the history, economy and culture of whiteness in the US. I truly believe that we don’t spend enough time trying to think critically about dominant categories, whether it’s hegemonic whiteness, normative heteroseuxality, or heteronormative masculinity.

What resources on whiteness might you recommend to Midd folk?

AM: There’s a document called White Supremacy Culture from Dismantling Racism: A Workbook for Social Change Groups, by Kenneth Jones and Tema Okun which is really useful for thinking about how white supremacy manifests covertly in group cultures. White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack by Peggy McIntosh is a good place to start for white people who aren’t sure how privilege affects their everyday lives.

AF: The podcast Scene on Radio did an excellent 14-part series on “Seeing Whiteness.” I think this can be an accessible place to begin for those who’d like to start their own work unpacking whiteness, drawing on the perspectives of both white people and people of color, and featuring some of the best scholars working in the field. It’s long, but absolutely worth the time spent.

KS: There are more to choose from than you might expect and ultimately it will depend on the readers’ objectives. But, if you want something “light” and “fun,” I’d start with Christian Landers’ Stuff White People Like. I like it because, intentionally or not, it hones in on the conspicuous consumption as an attempt to prove one’s belonging to a social class. If you’re looking to develop a bibliography, you can visit this research guide, What Is White Privilege? , that I started shaping while in grad school. And if you’re looking for people of color to lead the discussion, I Am Not Your Negro, a documentary film that centers the late author James Baldwin, a vocal critic of whiteness, conjures some serious food for thought. It’s available through go.middlebury.edu/kanopy, free to people within the Middlebury “community.” And, of course, come see the display.

LE: There’s so much! Here’s a copy of my syllabus, which includes:

- Grace Hale’s Making Whiteness;

- Michael Kimmel’s Angry White Men,

- Nancy Isenberg’s White Trash: The 400 Year Untold History,

- everything James Baldwin ever wrote but especially his 1964 Florida Forum interview,

- W.E.B. Dubois’ Psychological Reconstruction, especially on the psychological wage of whiteness, then how that’s used in

- David Roediger’s The Wages of Whiteness,

- Michelle Alexander’s, The New Jim Crow,

- Also the movie Get Out,

- Eminem’s “Slim Shady” video,

- so many novels like James Hannaham’s Delicious Foods,

- Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad.