Interesting animation. Question for consideration: Could this technique have greater significance outside of being an interesting spectacle?

READING: Breaking the Sound Barrier

I think our discussion about a dialogue between star, history and audience is extremely pertinent to Mark Juddery’s article. In the beginning of the article he mentions that Singin’ in the Rain became much more popular with time. Initially, it had a strong reception, but it only became considered one of the greatest films of all time more recently. I think this development demonstrates how important a film’s reputation is, allowing one generation to pass on their opinions to following generations, even altering a film’s recorded history with their own recollections. This latter aspect is also touched upon in Juddery’s article. He refers to the extensive research Kelly and his staff for Singin’ in The Rain underwent. They interviewed stars of the 1920s and used popular stories about the transition from silent to sound cinema to craft their plot. One direction the article does not go into–mainly because it is not the author’s particular interest to do so– is how this dialogue between stars, history and audience has a resounding effect, not only changing the perception of one film but instead changing society’s understanding of it entire oeuvre of films. The release of Singin’ in the Rain made musicals a legitimate genre again, extending past mere nostalgia for a genre lost. Musicals may not be as popular as other genres now a days, but its presence lives on, making appearances on film and in television (maybe one day there will be musicals in videogames as well). Singin’ in the Rain and its evolutional history is hugely responsible for this legacy.

READING: Fuller Chapter 8

I was struck by how similar marketing strategies are today to yesteryear. Back in the teens and 1920s, they were already developing stars as sponsors for a variety of commercial products, be they inane or practical, for “cars to candy bars” (151). Perhaps not nearly as surprising is the shared emphasis on beauty and attractive stars. Other similarities I noted was the search for the “perfect consumer” and the manipulation of the market. Addressing the former, younger audience members were heavily targeted by film magazines. In one section of the chapter, Fuller quotes a Kraft spokesman saying “in young woman ‘we find the least sales resistance.'” As said, it’s definitely not surprising but perhaps a little unsettling how fluid our marketing techniques have been. They have not changed much over the past century. They have always attempted to find and pinpoint where cash can be cultivated and reaped most efficiently. As to the latter, I was momentarily shocked to read how Fuller suspected the magazine of fabricating its editorial letters. Fuller hypothesizes that the magazines published letters that reflected a greater range of readership than they likely were to have. They wanted to portray even distribution throughout the country, in both rural and urban regions and even internationally abroad. Although shrewd, this strategy is dishonest and verging on sickening. I’ve never imagined that magazines now a days would do such a thing, but I suppose I wouldn’t put it past them either.

READING: Fuller Chapter 7

For my final project, I’m looking to do a creative piece, a 30-minute screenplay about a daughter and mother who have conflicting opinions about the newfound medium: film. The piece would take place in 1895, the same year the Lumiere’s Arrival of a Train at the Station came out. To aid my research, I would like to use my blog space as a brainstorming tool, fleshing out possible characters and their traits based on what I discover in the readings (I imagine I will do this for every other reading or so):

In Fuller’s chapter 7, Fuller says early on, “Fan magazine readers were not necessarily swooning women and giggly young girls,” (133). I note this because if my protagonist is a young girl I’ll want to avoid this stereotype. Her motivation for wanting to see Lumiere’s film should not make her out as being mawkish. Perhaps something more intellectual. She has an inquisitive nature. Perhaps, defying stereotypes, she is tomboyish, and already has an interest in the inner mechanisms of radios. She knows of and likes magic lanterns and other early cinematic devices. Later in the chapter, Fuller mentions “…the rude woman who refused to remove her hat in the theater or who gossiped during the show” (143). If ever converted to film viewing, the protagonist’s mother would be this type of fan. She is conservative in nature, prissy, pretentious and prim. She is religious and traditional, set in her ways. Fuller also mentions Mary Curtin, the fan of all fans, very devoted. I think my protagonist will share some characteristics with Mary: her determination and willingness to defy traditional roles– but not all her traits. I don’t envision her ever having “450 or 500 movie star portraits” (146) in her room. If she ever falls star-struck, she’ll be like Celia from Purple Rose of Cairo, and will fall for one man and not for the whole acting world.

READING: Narrative and Spectacle…Busby Berkeley and 42nd Street

After reading this article, I immediately wanted to return to 42nd street, which I had watched a day before. I had not watched it noting the importance of choreography to narrative or even knowing who the choreographer was. Now I can say confidently that the choreographer was Busby Berkeley, but I am still unsure of the choreography’s effect on the narrative. Patullo posits that Berkeley choreographies for realistic movies and have narratives that call for numbers set in said realistic contexts. Berkeley “suggests that impossibility is an inherent feature of the musical” (83), as does Kelley, in that he stylizes the numbers through camera movement and film editing. An example of this stylization in 42nd Street is when the camera glides between the showgirls’ bare legs. An audience member watching theater would never be able to take on such a perspective, although many male members might like to do so. So how does this aspect of Berkeley’s choreography affect the film’s narrative and therefore the audience’s experience? I would hypothesize that it provides the viewer with a momentary lapse, a break away from the film’s true narrative and a gateway into a world otherwise inaccessible for most viewers. I.e., it provides spectacle that is not necessarily pertinent to the plot. At the same time, however, the characters’ performance in the numbers, whether they perform the numbers well and whether the editing style reinforces this degree of success, relate to the narrative and its overarching character arcs. Thus, although Berkeley’s numbers are certainly considered spectacle, the editing style can also be narratively important.

READING: Fuller 4, 5 and 6

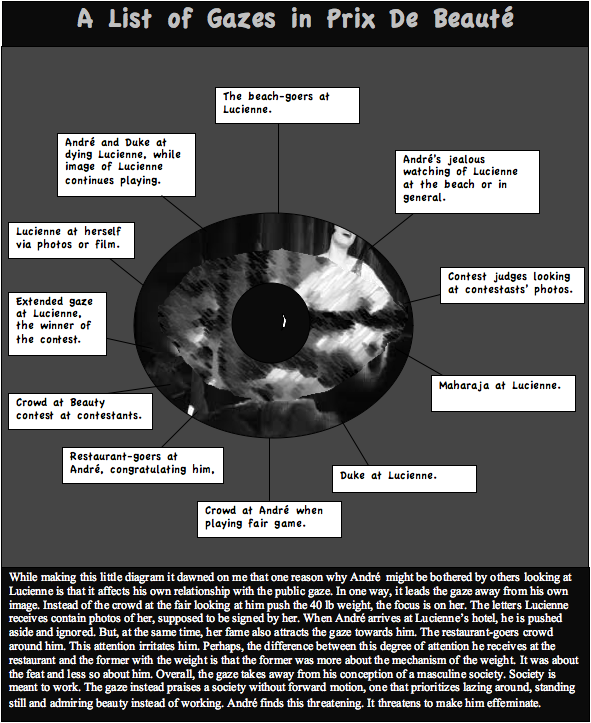

SCREENING: The Reflexive Gaze

As Lucienne attracts the public gaze, she notices her own appearance more readily and, as a result, her gaze is drawn away from André. While, yes, the public gaze objectifies her, it is also liberating. It allows her to break free from Andre’s narrow viewpoints, his jealousies and his cage-like philosophy of what is a proper role for a woman. At the same time, while André loses her gaze, he gains the public’s negative gaze, which looks onto him recognizing that he is an overprotective boyfriend. The gaze and the foreshadowing of its future progression are introduced to us in the beginning of the film when Lucienne is dancing by the pool. A crowd of men looks onto her and admires her physique. Upon noticing this development, André reprimands Lucienne and thus attracts the men’s gaze unto him. They note he is “jealous.” The gaze’s negative transference onto André allows Lucienne to retrospectively look back upon what she was doing and how she must have appeared from the men’s perspective, making her want to take on their point of view. Later, Lucienne and André go to a fair, and André performs a weight-throwing game in front of a crow while Lucienne looks on indifferently. André prefers this relationship: to be looked upon by his girlfriend in front of the whole world, but to not have anyone notice her attractiveness. A similar scene takes place in the end of the film in their dining room. André and Lucienne eat and face each other. André decides to relent and give Lucienne her fan mail and, upon doing so, the fan mail steals Lucienne’s look away from him and directs it downwards at the photos she is signing. This is troubling for André because Luciene is looking at photos of herself and is gaining too great a degree of self-recognition. She is beautiful and is able to see she is beautiful. It reminds André of the self-recognition she gained as Miss Europe. On the way to the beauty contest and upon arriving, she was the figure who was not only surrounded by the crowd and looked at, but was the one looking back onto the crowd, glorifying their gazes with smiles and turns. So what are the ramifications of Lucienne’s gaze back onto herself? For one, as mentioned, it liberates her, helping her recognize her beauty. But secondly, it exemplifies and embodies the America’s public’s desire to be movie star. The American public, and especially women, wanted to be watching themselves on screen as Lucienne does in the end of the film. A third point which is more difficult to prove without the help Hastie’s article, is that Louise Brooks was not only aware of her star persona, but manipulated it to her own desire and pleasure. In the film, Lucienne’s character has a more demure relationship with her screen image; she does not play around with her sexuality to the same degree, but she still analyzes her own image so she can modify it and adjust it within the public’s gaze.

READING: Lulu

READING: The Silence of the Silents

The article’s argument is clearly laid out throughout. Silent films were actually sometimes one hundred percent silent. There was a period of time in which music was not an inherent accompaniment to the cinematic image. What I found especially interesting was Altman’s conclusion that the existence of pure silence meant a lull in theatrical music accompaniment, therefore debunking the theory that music underwent a linear progression from Vaudeville to theatre to the movies. Altman instead claims that film music did not immediately develop from its predecessors but instead had to reinvent itself from silence. It may have been influenced by the past, but was not a growth budding uglily from its body of works, or a mere elaboration upon its former themes and tunes. Another aspect of Altman’s discussion which I enjoyed was the idea of ambiance music versus sounds that Mickey-moused the onscreen action. In other words, Altman viewed film’s period of true silence as influencing our eventual use of diegetic and non-diegetic sound. Although probably primitive at first, I can imagine the excitement that must have come along with the development of this new narrative balance, between silence and sound, an audience that is accustomed to silence and yet comprehends musical cues, and, lastly, the balance between story and the on-goings of real life and what must have been going on in these nickelodeons. Looking back upon the time period, the prospect of being a music accompanist would have been an adventure and an experiment well worth the passing silence.

READING: Fuller Chapter 2

At the end of Fuller’s chapter 2, she mentions that some, “exhibitioners, however, rated Sunday one of their most profitable business days; they continually fought to stay open, incurring fines and even jail sentences” (46). Along with cinema’s development, times were shifting and people’s values were changing. It’s interesting noting where and how people were willing to adjust their personal and cultural values in reaction to film’s rise in popularity. In this example, in the mid-Atlantic, exhibitioners were willing to give up their Christian values to make an extra buck and, if it were not for the law, it appears as if many an audience member would also have been equally willing to spend their Sundays leisurely watching movies instead of attending church. In the south, on the other hand, exhibitioners were not willing to make this sacrifice, but still dealt with the division between entertainment’s handling of vulgar subject matter and the church’s criticism of film. Again, we see the persistence of the conflict between church and town policy. But it is not only this religious quandary and its variations throughout the country that interest me. It is also the moral quandaries that arose and called out to be answered. A prejudiced south was forced to ask whether their biases and segregated theaters were more valuable to them than the black man’s nickel. In the north, a conglomeration of ethnicities came into contact as a result of cinema’s attraction, but, as Fuller says, women and girls amongst others were still sectioned off from the communal viewing experience. In sum, early film intersected with a cultural crossroad in which the country had to reevaluate its identity and morals.