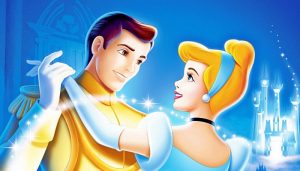

This picture of Cinderella with her Prince portrays the fairytale ending that consists of the Princess finding love. http://www.baxter.co.za/shows/cinderella-2/

Beginning with the Classical Era (1937-1967), Disney has created an image for little girls to strive for through the appearance of Disney Princesses. With the release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, expectations for how women should act in society were placed. The ideal princess was born and she is white, thin, beautiful “and ‘wins’ only if she attracts a powerful, male hero” (Wohlwend). Specifically, during the emergence of these princesses in the late 1930s, the audience – majority young girls – saw similarities in their role-models. In addition to the quintessential appearance of the Princess – beautiful, young and dressed semi-provocatively therefore “exposing [them] as sexualized beings” – these princesses share the same personality traits (May). Frequently, these women are affectionate, helpful, tentative and domesticated. These similarities are exhibited through Snow White’s enthusiasm for cleaning the Dwarves’ home, Cinderella’s role as the maid, and the many times when each Princess has been rescued by her strong, heroic lover. Children would watch as these women put others before themselves, usually to a fault; Ariel in The Little Mermaid is exemplary of this attribute. The underwater Princess gives up her ability to swim, her voice and her underwater kingdom in order to attract a boy. Behavior like this promotes anticipated identities for the audience. The corporation puts tremendous focus on appearances, instilling an imagined importance on being pretty into the young audience. Girls look at these Princesses and want to be pretty, and want to have a Prince. In one interview, Andy Mooney – head of the consumer products division at Disney – states that “we give girls what they want” (Orenstein 2011). This furthers the idea that the Disney foundation is built on superficial beliefs in what young girls “want.” And as Peggy Orenstein argues in her book, Cinderella Ate My Daughter, it’s hard to tell where the “want” ends and “coercion” begins (Orenstein 2011). As Mooney replies to this concern with some suggestion that girls grow out of these “phases.” What we are here to argue are the long-term effects these Disney Princesses have on girls, apparent or not. For example, the ample evidence that proves these figures have heightened the importance of sexiness and being pretty. These movies have created a duality: how and how not to be a girl. Instead of enforcing some freedom and empowerment in young girls to be whoever they want – to create their own definition of what it means to be female – they encourage them to be a certain way, to look like Cinderella and act like Ariel. The Disney Princesses’ reliance on men, domesticated behavior, lack of assertiveness and sexualized appearance generates an image for how women should both look and act.

Here is Cinderella meeting the social norms as a domestic women that are reinforced in the movie. http://therhetoricofdisney.weebly.com/gender.html

Movies, Disney Princess Films, and General Consumer Statistics

- Across the four hundred top-grossing G, PG, PG-13 and R-rated movies released between 1990 and 2006, only 27% of speaking characters were female

- Little has improved since then – of 5,554 speaking characters in G, PG, PG-13 and R-rated movies released between 2006 and 2009, only 29% were female

- Films directed/produced by women tend to feature a greater number of girls and women on screen

- When one or more women is involved in writing the script, the percentage of female characters jumps 14.3%

“The new Girlie Girlhood by the Numbers”

- The global revenue generated by Disney Princess products increased from $300 million in 2000 to $4 billion in 2009

- The percent of children ages 8-12 who regularly used eyeliner doubled between 2008-2010

- Girls ages 8 to 12 spend $40 million a month on beauty products – influence = mothers

- Socialization

- Barbie’s target audience when she was introduced in 1959: 9-12

- Age of barbie’s target audience today: 3-7

- 48% of girls in grades 3-12 polled in 2000 asserted that the most popular girls in school were “very thin”; 2006 – the number rose to 60%

Isabel Wyer