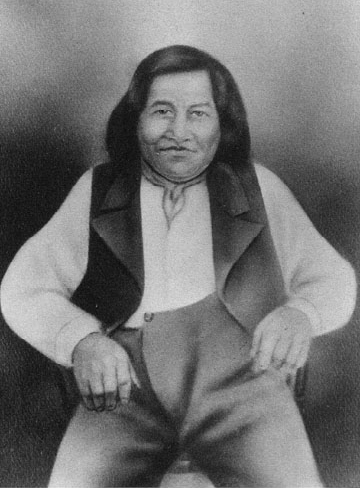

Sabael, an Abenaki man who became the first permanent settler of present-day Indian Lake, NY. Source: http://www.nedoba.org/bio_benedict01.html.

Before European colonization of North America, Algonquian and Iroquoian peoples inhabited the area surrounding Lake Champlain. Indigenous settlements in the region were centered around the Champlain Valley as well as the nearby Mohawk and St. Lawrence valleys, while the Adirondack mountains served primarily as hunting grounds for the peoples who inhabited the nearby valleys. [ref] Terrie, Contested Terrain. [/ref] Around the time that Europeans first came to the region, the Abenaki—an Algonquian tribe—occupied the area approximately from Lake Champlain eastward through New Hampshire, while the Mohawk—one of the six members of the Iroquois Confederacy—occupied the area from Lake Champlain westward along the Mohawk River and northward into the St. Lawrence Valley. [ref] Lounsbury, Iroquois Place-Names in the Champlain Valley. [/ref] However, territorial boundaries between neighboring indigenous peoples historically were not strict, and overlapping hunting territories were common, as was the case for the Abenaki and the Mohawk. [ref] Day, In Search of New England’s Native Past. [/ref]

The Western Abenaki had settlements up until the eighteenth century at the mouths of Otter Creek and the Winooski, Lamoille, and Missisquoi Rivers and also on Grand Isle, but eventually these communities concentrated at the Missisquoi settlement. Historically, Abenaki families traveled widely across the Lake Champlain region in birchbark canoes in the summer and on snowshoes in the winter, sustaining themselves for generations by hunting species including moose, deer, bear, waterfowl, and passenger pigeon; fishing, especially for eel; gathering wild foods such as butternut, berries, maple sugar, and greens; and planting corn, beans, and squash. Abenaki people mostly lived and traveled in family groups, but in times of conflict communities selected leaders for war parties. The Abenaki allied with other neighboring Algonquian peoples living primarily to the east and north, while they often fought with the Iroquois nations to the west. [ref] Ibid. [/ref]

The Mohawk, who call themselves Kanienkehake (“People of the Flint”), primarily had settled in the Mohawk Valley of New York by the eighteenth century, but claim an original homeland that extends into southern Canada and Vermont as well. [ref] St. Regis Mohawk Tribe, “Culture and History.” [/ref] The Mohawk formed a peaceful alliance with four other Iroquois tribes that occupied most of northern and western New York but “roamed wide over eastern North America” to create the Iroquois—or Haudenosaunee—Confederacy approximately a century before European colonization. The alliance remained a powerful political entity that “had to be reckoned with by all of the colonial powers until the close of the Revolutionary War.” [ref] Lounsbury, Iroquois Place-Names in the Champlain Valley. [/ref] The Mohawks were the first to join this Confederacy, and are known as the “Elder Brothers” of the Iroquois as well as the “Keepers of the Eastern Door”. The Mohawk traditionally lived in the distinctive Iroquois multi-family homes known as longhouses, and cultivated large fields with corn, beans, and squash, supplementing this diet by hunting, fishing, and trapping. [ref] National Museum of the American Indian, “Background Information on the Akwesasne Mohawk.” [/ref]

Mitchell Sabattis, a famous Adirondack Guide. 1886. Source: Adirondack Museum [STILL NEED PERMISSION].

With the arrival of Europeans in the seventeenth century, the Champlain Valley became “a cultural meeting ground where Algonquian and English, Iroquois and French, contended and interacted.” [ref] Calloway, The Western Abenakis of Vermont, 1600–1800. [/ref] Over the following centuries, securing European control of the region “entailed more than simply settling the land; it required the dispersal, dispossession, and expulsion of native inhabitants,” and European settlers and traders also brought widespread epidemics to indigenous communities which suffered greatly from introduced diseases such as smallpox [ref] Ibid. [/ref] As British settlers expanded northward in New England and New York, the Abenaki—allied with the French enemies of the British—often raided frontier settlements. Ultimately, however, many Abenaki people in the Champlain Valley fled northward to other Native communities near or beyond the Canadian border as a result of settler encroachment on their traditional lands, while others remained on their territory. [ref] Day, In Search of New England’s Native Past. [/ref] For the Mohawks, the expansion of settler colonialism in New York forced communities to relocate in the eighteenth century northward into the St. Lawrence Valley, where they allied with the French. [ref] National Museum of the American Indian, “Background Information.” [/ref] Some Abenakis took refuge with these French-allied Mohawks, with whom they formed part of the Seven Nations of Canada, [ref] Bonaparte, “The History of Akwesasne from Pre-Contact to Modern Times” [/ref] and a handful also took up residence in the Adirondack mountains. Some of these Adirondack Abenaki refugees became legendary wilderness guides, including Sabael—an Abenaki man from Maine who was the first settler at Indian Lake and guided Ebenezer Emmons on his climb of Mt. Marcy—and Mitchell Sabattis—a famous Long Lake guide who worked with Verplanck Colvin’s surveying team. [ref] Terrie, Contested Terrain. [/ref]

It is important to remember, also, that the history of indigenous oppression across North America did not end with the arrival of settlers who displaced and wiped out Native communities. Abenaki people were persecuted, for instance, by the Eugenics Survey of Vermont well into the twentieth century. Through the eugenics program, at least an estimated 200 Abenaki people were sterilized without full informed consent from approximately 1925-1936, and forced sterilizations of Abenaki people continued at least until the late 1950s. The program labeled indigenous peoples living on the margins of Vermont society as “mentally deficient”, “gypsies”, and “pirates” to justify the government-sponsored practice of sterilizing and eliminating poor and marginalized communities. [ref] Dann, “From Degeneration to Regeneration, The Eugenics Survey of Vermont, 1925–1936.” [/ref] Through programs and attitudes such as those demonstrated by the eugenics program, the Abenaki and other indigenous groups across North America have continued to face structural violence, the traumas of colonialism, and social exclusion in the centuries since European colonization began.