Political conditions were about to affect Kandinsky’s life again. Toward the close of the 1920s, the National Socialists stepped up efforts against the Bauhaus, and the Desau National Socialists demanded the immediate closure of the school. As Kandinsky taught his theoretical course on artistic design for the last time in 1930, he included scientific material from the fields of botany, zoology, astrology, and crystallography (Taschen p. 166). This is very much in keeping with the teachings of anthroposophy, which pursued the scientific way of examining or creating art. In 1933, after the Bauhaus in Desau had closed and relocated to Berlin, the Gestapo demanded Kandinsky’s dismissal. In July 1933, the faculty unanimously voted to dissolve the Berlin Bauhaus (Taschen p. 168). Kandinsky, as a foreigner, an abstract painter, and a teacher, was unwelcome in Hitler’s Germany. He and his wife moved to Paris in 1933.

Kandinsky struggled upon his arrival in Paris. Cubism and Surrealism dominated the French market, and abstract art was not well regarded.

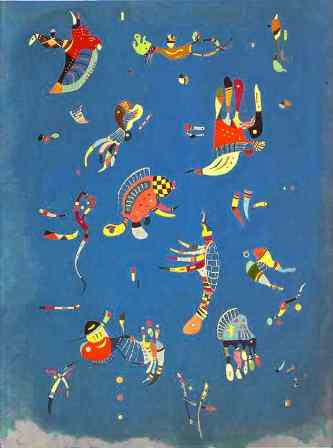

The painting below is representative of Kandinsky’s forms during his Paris years. They bear a striking similarity to the forms used by early cultures. Kandinsky embraced this connection with earlier peoples, saying

“Our sympathy, our understanding, our inner feeling for the primitives arose partly in this way. Just like us, those pure artists wanted to capture in their works the inner essence of things, which of itself brought about a rejection of the external, the accidental.”

(Taschen p. 171)

These sentiments are again reflective of anthroposophical philosophies of stripping away the external in the quest for the inner, higher spiritual life.

Sky Blue (1940)

Kandinsky also returned to the publishing world in Paris, publishing essays defending abstract art. The first of these had been published in 1931 in Cahiers de Art. Kandinsky wrote more than a dozen essays advocating abstract art during his years in Paris. Despite these hindrances to abstract artists in Paris, Kandinsky devoted himself to his work. After a long break, he resumed the use of the title “Composition.” This title, as discussed, denoted the highest level in his pictorial hierarchy (Taschen p. 173). Most of Kandinsky’s Compositions were completed in Murnau; only one was produced at the Bauhaus. He painted the final two in Paris.

Composition IX, seen below, highlights the contrast between the formally rigorous ground, which is divided into vibrant diagonal strips, and the unregulated forms floating above it. The division of the pictorial plane inot diagonal strips is unique amongst Kandinsky’s works. The directional impulse created by the direction of the diagonal strips is highlighted by their colors, which on the left resemble the primaries (yellow, blue, and red) and on the right the secondaries (violet, orange, and green). This painting was purchased by the Jeu de Paume museum, and became the first large abstract painting to enter the collection of a French museum.

Composition IX (1936)

Kandinsky’s paintings in his final years reveal no common denominator. He combined his conceptions of “fairytale” and “reality” to create a world that could only exist in painting. His works reveal a trend toward natural forms, seemingly representative of forms on the molecular level in biology. This can be seen to some extent in Composition IX. Toward his death, Kandinsky increasingly allowed his forms to float freely in space, as seen in Sky Blue. This meant sacrificing the geometric elements for an atmospheric, pictorial space (Taschen p. 174).

Kandinsky’s works were largely not accessible to the public toward the end of his life. Many works were in the U.S. or in Russia, and many of his Munich works were still cared for by Gabrielle Munter.

In 1939, Kandinsky and his wife applied for and received French citizenship. They moved from Paris to Neuilly after the Germans occupied Paris. As Kandinsky approached increasing political difficulties, he moved into the negative-positive effects that could be expressed by black and white. He painted his last Composition in 1939. Composition X (below) is an example of unity and harmony. Its freefloating forms invoke the resemblance of constellations that follow the laws of harmony (Tashcen p. 184).

Composition X (1939)

Kandinsky continued to paint every day until the end of July in 1944. He was suffering from arteriosclerosis and losing strength, and died on 13 December 1944 at the age of 78.

Kandinsky summed up his works in an article he wrote in 1937:

My painting does not try to reveal “secrets” to you… I have not found a “special language” that has to be “learned” and without which my painting cannot be read. This should not be made more complicated than it really is. My “secret” consists solely of the fact that over the years I have obtained that fortunate skill (have maybe fought for it unconsciously) to liberate myself (and with that my painting) from “destructive secondary sounds,” so that each form comes alive – acquires sound and consequently expression, too… Here, I do not need worry about the “content,” but solely about the right form. And the correctly extracted form expresses its thanks by providing the content all by itself… The content of painting is painting.